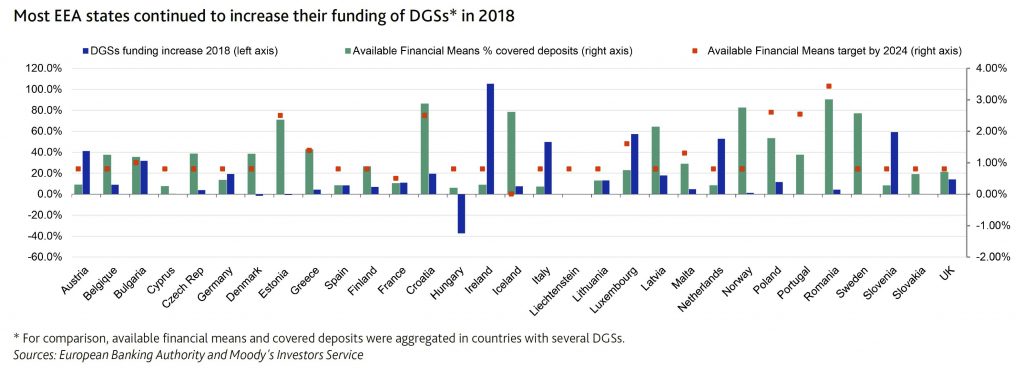

On 17 June, the European Banking Authority (EBA), published 2018 data on national Deposit Guarantee Schemes (DGSs) across the European Economic Area (EEA), which show that 32 of 43 DGSs increased their funds available to cover deposits in 2018 by levying banks.

Here of course the $250k deposit scheme is unfunded and currently inactive.

Moody’s says that the target of 0.8% of covered deposits by 2024 set out in the Deposit Guarantee Schemes Directive (DGSD) has already been achieved in 17 of the 43 DGSs in the EEA. The gradually increasing harmonisation of DGSs in Europe is credit positive for European banks because it improves European banking systems’ financial stability by better protecting depositors against the consequences of credit institution insolvency. As DGS funding increases and exceeds the 0.8% threshold, they also expect banks’ levies to moderate, which will benefit their profitability.

Since the 2009 financial crisis, European authorities developed policies and tools to buttress financial systems’ resiliency and help authorities prevent and, if needed, tackle bank distress without having to resort to taxpayers’ support. DGSs form one of these tools.

Under current EU legislation, depositors are protected by their national DGS up to €100,000 (or the equivalent in local currency). This protection applies regardless of whether ex ante funding has been accrued by DGS. Under the DGSD, all EEA banks are required to contribute to national DGSs so that at least 0.8% of covered deposits are funded by 2024 (and by exception, no less than 0.5% of the covered deposits, like in France2).

Nine member states have set up DGSs with higher funding targets such as Romania (3.43%) and Poland (2.6%). Some countries, such as Iceland, have not yet defined their national funding target, while others have defined numerous DGSs for different categories of banks and depositors, as in Germany for private, public, savings or cooperative banks, hence there are more DGS than there are EU countries.

As of year-end 2018, 16 countries had already reached the DGSD’s 0.8% minimum funding ratio for 2024, and 10 countries exceeded their national target. The levies banks paid increased by around 12% in 2018, while covered deposits grew only by 3.6%. As of year-end 2018, EEA member states had reached in aggregate a funding ratio of 0.65% of covered deposits, up from 0.6% in 2017.

Out of the 31 banking systems addressed in the EBA report, 25 increased the funding for the DGSs in 2018, with very large increases in Ireland (+105.2%), Slovenia (+59.2%) or Luxembourg (+57.3%). The diversity in funding efforts reflects different starting points since some countries did not have DGS or limited ex-ante funding when the DGSD was adopted. For instance Luxembourg had no funding in 2015 and a target of 1.6% of covered deposits.

Despite progress, the third pillar of the banking union – the European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS) proposal adopted in 2015 – is not yet in sight due to a lack of political consensus. The EDIS proposal builds on the system of national DGSs and would provide a stronger and more uniform degree of insurance cover in the euro area. This framework would reduce the vulnerability of national DGSs to large local shocks.