FinTech could mean a more open, more transparent, and more democratic global financial system according to Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, in a speech “Enabling the FinTech transformation – revolution, restoration, or reformation?”. He also announced the Bank is launching a FinTech Accelerator to work in partnership with FinTech to help harness FinTech innovations for central banking. He concludes that FinTech should neither be the Wild West nor strangled at birth.

The Potential impact of FinTech on financial and monetary stability

FinTech has the potential to affect monetary policy transmission, the safety and soundness of the firms we supervise, the resilience of the financial system, and the nature of shocks that it might face.

It could also have profound implications for the Bank’s secondary objective, as supervisors, to facilitate effective competition between the firms we regulate.

The impact on firms’ safety and soundness depends on several factors. By making wholesale and retail settlement faster and capital allocation more efficient, FinTech could boost banks’ returns and therefore viability.

Already, FinTech is spurring new entrants including payments providers, peer-to-peer lenders, robo advisors, innovative trading platforms, and foreign exchange agents. This could, with time, unbundle traditional banking models and deny banks their traditional economies of scale and scope.

The systemic consequences of FinTech are even more complex. More diverse business models and alternative providers are positives for financial stability. By allowing better credit screening and less adverse selection, FinTech could improve risk assessment, credit allocation, and capital efficiency. But if it encourages herding on common information, trading positions could become more correlated. And if switching costs in funding markets fall, liquidity risk could rise and systemic risks grow.

Indeed, sometimes when I hear of democratising finance, spreading risk in capital-light originate-to-distribute models, I think I haven’t been this excited since the advent of sub-prime.

FinTech could also affect the conduct of monetary policy. Unbundled banking would change the roles of bank capital and funding costs in the credit channel of monetary policy. If FinTech enhances participation in financial markets, the wealth channel of monetary policy could strengthen.

More broadly, Big Data techniques could tell us about the state of the economy more accurately and promptly. Forecast performance could improve, akin to the forecast improvements that better measurement of atmospheric conditions has, over time, delivered for meteorologists.

My own forecast is that FinTech’s consequences for the Bank’s objectives will not become fully apparent for some time. Many of the technologies needed to deliver such transformations are nascent – their scalability and compatibility untested beyond Proofs of Concept. Moreover, the bar for displacing incumbent technologies is very high. Nor will the Bank of England take risks with the resilience of the core of the system. Disruption won’t come either easy or cheap.

Enabling the FinTech Transformation

We are actively exploring how new financial technologies could support our policy objectives. There are five ways the Bank is enabling the FinTech transformation.

The first is widening access to central bank money to non-bank Payments Service Providers, known as PSPs.

As the internet revolutionised commerce, making trade faster and markets more competitive, payments technology lagged in many countries, although it is worth remembering that the UK has been a global leader on real-time retail payments. Faster Payments (FPS) was one of the earliest real-time retail systems introduced, in 2008. Now, new entrants and established players are seeking to provide payment services that are instantaneous, secure, reliable and accessible anytime from anywhere.

Retail consumers and firms are increasingly demanding payments completed in seconds, not hours or days.

They expect payments to be seamless, reliable and cheap whether to recipients overseas or just up the street.

And they expect to make payments without visits to a bank branch or even logging onto a desktop computer.

Similarly, companies, financial intermediaries and governments want to process ever larger and more complex bulk payments covering multiple systems, countries and currencies.

Central banks lie at the hearts of payment systems, giving households and firms the assurance that transactions have settled in the most secure form of payment: central bank money. To fulfil that role, our payments infrastructure needs to remain fit for purpose: reliable, resilient and robust. But we must also be responsive to changing payments demands. So earlier this year the Bank announced we would be drawing up a blueprint to replace our current real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system, now twenty years old.

48 institutions currently have settlement accounts in RTGS. All other users of the systems that settle across RTGS access settlement via one of four agent banks. These users include over 1000 non-bank PSPs serving customers’ increasingly demanding standards, and many rely on major UK payment schemes, particularly Faster Payments (FPS).

As they grow, some PSPs want to reduce their reliance on the systems, service levels, risk appetite and goodwill of the very banks with whom they are competing. Re-selling services ultimately provided by banks limits these firms’ growth, potential to innovate, and competitive impact.

That is why I am announcing this evening that the Bank intends to extend direct access to RTGS beyond the current set of firms, allowing a range of non-bank PSPs to compete on a level playing field with banks.

By increasing the proportion of settlement in central bank money, diversifying the number of settlement firms, and driving greater innovation in risk-reducing payments technologies, expanding access should bring financial stability benefits. It should also enable more efficient, effective and inclusive payments, including in ways that we cannot fully anticipate.

It is not a one-way street, however.

As we extend access, we will safeguard resilience in three ways: by holding settlement account holders to the appropriate standards; by removing legislative barriers to non-bank access; and by designing the right account arrangements for new entrants.

I am pleased that both the FCA and HMRC, who together supervise these institutions, are committed to developing a strengthened supervisory regime for those who apply for an RTGS settlement account, to give assurance that non-bank PSPs can safely take their place at the heart of the payment system.

And I welcome the Chancellor’s commitment tonight to make the necessary legislative changes to ensure that these new entrants can access RTGS safely and efficiently.

By extending RTGS access, our objective is to increase competition and innovation in the market for payment services. To ensure that PSPs are not disadvantaged relative to banks offering equivalent payment services, the Bank intends to give appropriate remuneration for balances that PSPs will be required to hold overnight to support their payments activities.

The second way the Bank is enabling the FinTech transformation is by being open to providing access to central bank money for new forms of wholesale securities settlement.

Securities settlement is the lifeblood of modern wholesale financial markets – the associated payments account for fully half of RTGS’s daily settlement flows.

However, as with retail payments, securities settlement is now ripe for innovation. A typical settlement chain can involve many different intermediaries, meaning securities settlement is comparatively slow. Transactions that take nanoseconds to execute settle in days. This also means large costs and operational risk. And, like in payment systems, economies of scale introduce concentration and create single points of failure. All of that ties up potentially tens of billions of pounds worth of capital. With the economics of wholesale banking under pressure, cutting inefficiencies is a high priority for industry.

That is why it is welcome that FinTech innovators are exploring the potential of distributed ledger technology to simplify the settlement chain, reduce its cost, and raise its speed while increasing resilience. The instruments involved range from equities to bank loans. However, the challenges facing such projects are legion, including reliability, resilience, security and scale. And fundamentally, how to prove technologies that are still nascent?

One challenge an otherwise robust system of sufficient scale would not face is access to central bank money from the Bank of England. The Bank has for many years sought to ensure that, wherever possible, wholesale securities settlement occurs in central bank money.

We are already clear that we stand ready to act as settlement agent both for regulated systemically important schemes supervised by the Bank, and, on a case-by-case basis, for other new systems.9 The Bank will use this to enable innovation and competition, without compromising stability.

The third way the Bank is enabling the FinTech transformation is by exploring the use of Distributed Ledger (DL) technology in our core activities, including the operation of RTGS.

If distributed ledger technology could provide a more efficient way for private sector firms to deliver payments and settle securities, why not apply it to the core of the payments system itself?

The great promise of distributed ledgers for central banks is their potential to enhance resilience. Distributing the ledger means multiple copies of the system. It can continue to operate if parts get knocked out. That removes the single point of failure risk inherent in a centralised system.

But if we are to entrust the heart of our financial system to such technology, it must be robust and reliable. The payments system we oversee processes £½ trillion of bank transactions, equivalent to around 1/3 of annual GDP, each day. Disruptions are potentially costly. That is why, in payments and settlement, the Bank has an extremely low tolerance for any threat to the integrity of the economy’s ‘plumbing’. We won’t beta test RTGS.

To help distinguish DL’s potential from its hype, the Bank has set up our own as a Proof of Concept. We have learned a great deal – about the opportunities and the challenges that need to be met before DL could be used in central banking.

Some of those challenges are familiar to any payments system.10 Others are more specific to DL. For example, we would need assurance that DL systems can be scaled, retain data integrity, and operate at the speeds and volumes required by central bank infrastructure – day in, day out.

And we need to be certain that the privacy of the data in those distributed copies cannot be compromised by cyber attack, not just today but in the future. One way this might be achieved is to limit the distribution of the ledger to existing trusted parties, such as other public sector entities.

To move forward we are working with other central banks. Beyond this we are open to working with others to explore further possibilities, including alternative applications of the technology.

In the extreme, a DL for everyone could open the possibility of creating a central bank digital currency. On some levels this is appealing. For example it would mean people have direct access to the ultimate risk-free asset. In its extreme form, it could fundamentally and perhaps abruptly re-shape banking.

However, were it to co-exist with the current banking model, it could exacerbate liquidity risk by lowering the frictions involved in running to central bank money.11 These questions and others are why these topics are being examined as part of the Bank’s research agenda, with the prospect of a central bank digital currency for the UK, in my view, still some way off. We will work to make payments easier, and though cash may no longer be king it once was, its reign will endure for some time.

The fourth way the Bank is enabling the FinTech transformation is by partnering with FinTech companies on projects of direct relevance to the Bank’s mission.

I am announcing tonight that the Bank is launching a FinTech Accelerator to work in partnership with FinTech firms on challenges that we, as a central bank, uniquely face. The Accelerator will work with new technology firms to help us harness FinTech innovations for central banking. In return, it will offer firms the chance to demonstrate their solutions for real issues facing us as policymakers, together with the valuable ‘first client’ reference that comes with it. With time, the Accelerator will build a network of firms working in this space for the benefit of us and them alike.

How will this help us?

Consider that the Bank monitors risks that threaten the operational resilience of the UK financial system.

At the Financial Policy Committee’s instigation, we have been working with other authorities to encourage firms to improve their cyber defences.

Over the past two years, twenty-three firms have undergone CBEST penetration tests, with all core banks expected to have completed tests by the end of this year.

To complement these efforts, the Bank has begun examining how public data could be used to assess firms’ cyber resilience, including looking for malware on a firm’s systems, software vulnerabilities, or weak encryption that could be exploited by hackers.12

As a proof of concept and good cyber hygiene, we are using data publically available on the web to assess our own resilience. Early results indicate these techniques could complement existing tests in our regular assessments of firms’ operational resilience.

We are also exploring how we – and others – could use the data the Bank collects more effectively. Big Data has the potential to help the Bank’s policy committees identify trends in systemic risk and the economy. Much of the data we collect is rightly subject to strict limits on confidentiality and sharing. For example, our regulatory mortgage contract data comes under strict control to guarantee personal data protection. We can’t just share the private data to which we have access with external researchers, foreign authorities or even across the Bank.

But this means that, simply put, the people of the United Kingdom are not getting the most out of the data the Bank collects.

That’s why we are investigating ways of anonymising and de-sensitising data – fully respecting privacy laws without losing analytical content – to allow wider sharing.

Progress has been encouraging creating the prospect of better informed policy making.13

These are just two examples of a bigger programme of collaboration between the Bank and technology innovators. We are open to further collaboration and tomorrow will provide details of the next steps.

Finally, the Bank is calibrating its regulatory approach to FinTech developments.

FinTech should neither be the Wild West nor strangled at birth. The Bank is devoting considerable resources to ensure whatever develops is sustainable, not ephemeral.

If FinTech enables a great unbundling of financial services, risks will change in tandem.

Our interest is in ensuring the safety and soundness of banks, the protection of insurance policy holders and the resilience of financial ecosystem as a whole to these changing risks. It is about activities not labels.

That is why the Bank has been engaging with FinTech firms to understand better the financial stability risks that could emerge as banking is re-shaped. We will monitor those that arise along the transition path and those that could endure.

Where firms or activities become systemic and risks to the real economy grow, they will come within the purview of the Bank’s responsibilities for the stability of the system as a whole. The Financial Policy Committee will continue to monitor the scope of the regulatory perimeter. Adjustments will follow if necessary.

When FinTech companies fall within our remits, we will monitor them in the same proportionate way that we approach other firms – backed by analytics and judgement, taking action where appropriate.

We are building a system that allows for orderly failures. Not just to end the blatant unfairness of Too Big to Fail, but also to foster industry dynamism and better outcomes for consumers. After all, ease of exit promotes ease of entry. We won’t discourage avatars by preserving dinosaurs.

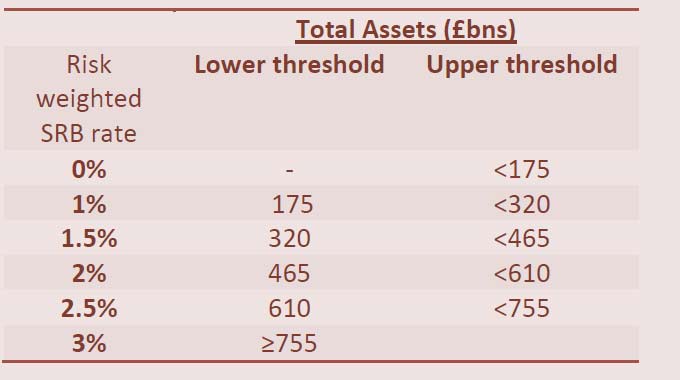

Given competition in the sector, this strong growth profile raises the risk that firms could relax their underwriting standards in order to achieve their plans. The review further highlighted that some lenders were already applying underwriting standards that were somewhat weaker than those prevailing in the market as a whole.

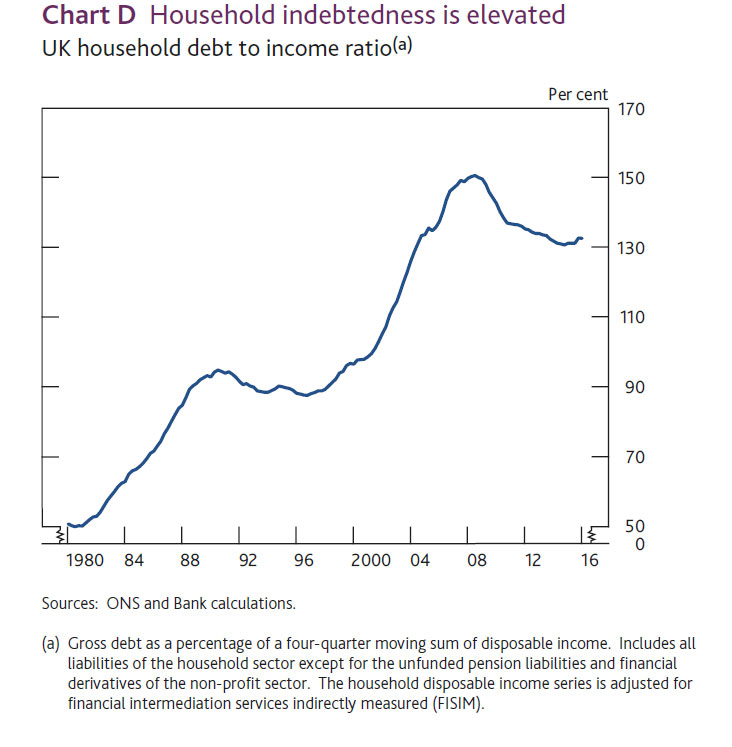

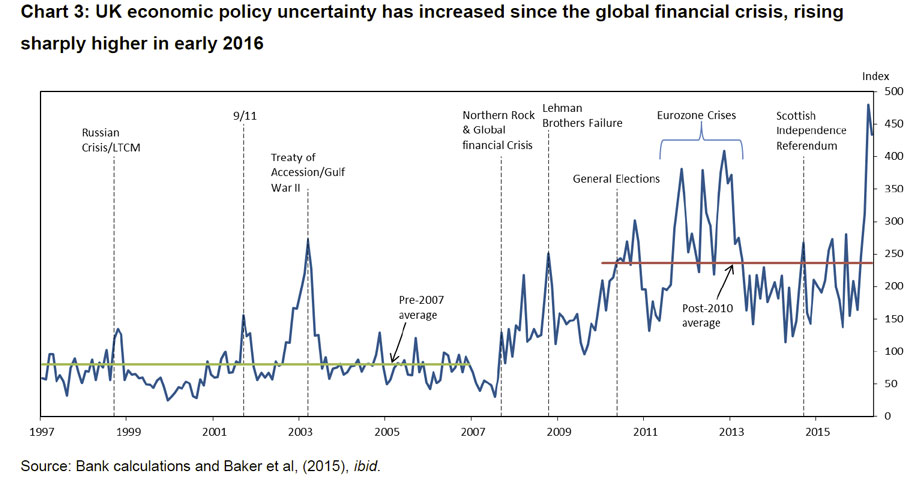

More broadly, The Stability Report highlighted the risks to the UK economy, especially around Brexit. The webcast is worth listening to.

More broadly, The Stability Report highlighted the risks to the UK economy, especially around Brexit. The webcast is worth listening to.

In a speech to the London Business School

In a speech to the London Business School