Broadcast on Thursday 28th November 2019, Nucleus Wealth’s Head of Investment Damien Klassen, Head of Operations Tim Fuller, and founder of Digital Finance Analytics, Martin North discuss “Australia’s Housing Market Dilemma.”

Category: Economics and Banking

QE ‘not on the agenda’: Lowe (?)

According to an article in InvestorDaily, RBA Governor Philip Lowe has poured water on the prospects of quantitative easing (QE), saying Australia “shouldn’t forget about fiscal policy” to prevent a recession.

“QE is not on the agenda at this time,” Governor Lowe told at the annual dinner of the Australian Business Economists.

Interest rates will have to hit 0.25 per cent before the RBA considers QE – something that economists are predicting by mid-2020. But Governor Lowe doesn’t think QE will be necessary, saying that the Australian economy is in a good position and that the RBA will achieve its goals.

“At the moment, though, we are expecting progress towards our goals over the next couple of years and the cash rate is still above the level at which we would consider buying government securities.”

However, Governor Lowe hinted again that he would prefer the use of fiscal policy rather than monetary policy to ward off a recession, citing a report from the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS), which he recently chaired.

“The report also notes that there may be better solutions than monetary policy to solving the problems of the day,” Governor Lowe said.

“It reminds us that when there are problems on the supply-side of the economy, the use of structural and fiscal policies will sometimes be the better approach. We need to remember that monetary policy cannot drive longer term growth, but that there are other arms of public policy than can sustainably promote both investment and growth.”

Governor Lowe also said that the willingness of central banks to provide liquidity could reduce the incentive for financial institutions to hold their own adequate buffers and create an “inaction bias” from prudential regulators or fiscal authorities.

“If this were the case, it could lead to an over-reliance on monetary policy,” he said.

The sentiments about quantitative easing have been echoed by fund managers. Sarah Shaw, chief investment officer at 4D infrastructure and Chris Bedingfield, principal at Quay Global Investors have urged the government to instead allocate investment in infrastructure to create jobs and boost productivity.

Ms Shaw noted the need to replace roads, bridges and other structures with better planned “forward-thinking” infrastructure is high.

“If you think about the need for infrastructure spend that I’m talking about, if you put a number on it, it’s maxed at $4 trillion by 2040 of infrastructure capacity that’s needed,” she said.

“If you think about that and you’re in an interest rate environment as low as it is today, if you’re not borrowing to invest in a much-needed infrastructure, then there’s something wrong.”

She added she looks for companies that are locking in fixed term bet to invest for future cash flows, because “now is the time to do it” with the current low cash rate.

“Why shouldn’t countries be doing that?” Ms Shaw queried.

“I’ll give you an example: China during the GFC, biggest form of quantitative easing – 35,000 kilometres of high-speed rail. That’s the sort of quantitative easing that we should be looking at here in Australia.”

VanEck has predicted there will be more rate cuts in 2020.

As discussed with John Adams in our recent post, we did not come away with the same conclusion, and Westpac, for example is forecasting QE will hit during 2020.

RBA’s Plan For “Zero” Rates

Last night, in a much anticipated speech broadcast live on the Reserve Bank’s website, Governor Phil Lowe laid out in very clear terms the circumstances in which the bank would resort to quantitative easing and the way in which it would implement it. Via The Conversation.

Quantitative easing is simply a change in the way it eases monetary policy when the official interest rate approaches zero.

Usually it does it by cutting the so-called cash rate, which is the rate banks pay each other for money deposited overnight.

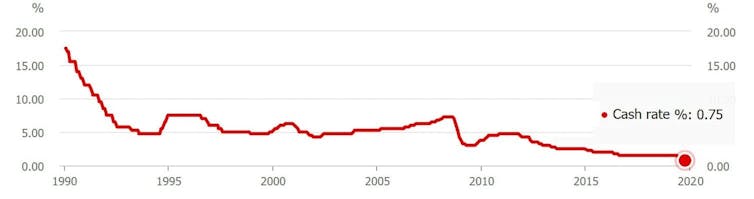

Eight years ago the cash rate was 4.5%. Three years ago it was 1.5%. After the most recent three cuts in June, July and October, it is just 0.75%

Last night, Governor Lowe said the effective lower bound was 0.25%. Rather than let the cash rate get any lower or negative (an option he explicitly ruled out), the bank will push down other longer-term rates by buying government bonds.

It’s the “quantitative easing” approach adopted by the US Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014.

Government bonds are sold by governments in return for money, a means of borrowing. The buyer gets guaranteed interest payments and a guarantee that their money will be returned in full after three, five, ten or even 20 years depending on the length of the bond.

Once issued, bonds can be traded on a market, and the price at which they change hands can be expressed as an implied interest rate, which becomes the risk-free rate against which all other interest rates are benchmarked.

How quantitative easing would work

Buying bonds from investors would push down that risk-free rate, pushing down the entire structure of long-term interest rates.

All other things being equal, this should also push down the exchange rate by reducing the return on Australian dollar denominated financial investments.

Governor Lowe indicated he might buy state government bonds as well as Commonwealth bonds.

Importantly, he argued that although the bank would be mindful of the need to ensure private banks had enough access to the bonds they needed to hold for regulatory purposes, those holdings would not be an impediment to quantitative easing.

He ruled out buying residential mortgage-backed securities and other private assets given that those markets are currently functioning well and Reserve Bank purchases could distort them.

The approach borrows heavily from the US Fed.

As in the US, Lowe says quantitative easing would be complemented by “forward guidance,” where the Reserve Bank would signal early how long-term interest rates would be kept low and the circumstances in which it expected to raise them again.

The guidance is designed to influence market expectations for future interest rates, enhancing the effectiveness of cuts in long term interest rates.

When it would happen

In addition to “how,” Governor Lowe spelled out “when” – the economic circumstances in which the bank would resort to quantitative easing.

It would do it when the cash rate was at 0.25% and inflation and unemployment were moving away from its objectives.

The bank targets 2-3% inflation on average over time and has recently identified 4.5% as the “full employment” unemployment rate.

Importantly, Lowe emphasised that the Australian economy has not yet reached the point where a cash rate as low as 0.25% would be needed and argued quantitative easing was unlikely to be needed in future.

The cash rate is at present 0.75%. Setting 0.25% as the effective lower bound gives the Governor 0.5 percentage points left to cut before implementing quantitative easing.

Implicitly, Governor Lowe is saying that those cuts of 0.5 percentage points will be enough to stabilise the economy.

A pause for a breath at 0.25%

Lowe also indicated the bank would not seamlessly transition to quantitative easing.

He implied there was an additional hurdle or threshold that would need to be crossed, suggesting he would be reluctant to make the transition.

His big problem is that neither inflation nor the unemployment rate are moving in the right direction.

The bank has undershot its inflation target since the end of 2014, giving the economy a weak starting point going into an emerging global downturn.

My research on the US experience for the United States Studies Centre shows that the main problem with is quantitative easing was that it was not done soon enough or aggressively enough.

It might be better to be bold

While quantitative easing was effective, it could have been made more so had what was going to happen been made clearer.

The Fed went out of its way to limit the transmission of quantitative easing to the rest of the economy, fearful it would be too potent and lead to excessive inflation.

Those concerns proved misplaced. By pulling its punches, the Fed ended up being less effective and having to pursue quantitative easing for longer than if it had used it more aggressively.

Governor Lowe’s very obvious reluctance to go down the quantitative easing route suggests the Reserve Bank is in danger of making the same mistake, but it is not too late to learn from what happened in the US.

Author: Stephen Kirchner Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Australia’s Economic Emperor Will Unleash Monetary Madness!

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North discuss the recent RBA speech on Unconventional Monetary Policy: Some Lessons From Overseas.

NAB To Offer Government FTB Mortgages

NAB has announced it will be taking part in the government’s first home loan deposit scheme, operational from 1 January 2020. Via Australian Broker.

The bank has been selected by the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) to offer mortgages under the scheme.

“We are proud to be chosen to partner with the federal government and NHFIC,” said Mike Baird, NAB chief customer officer of consumer banking.

“Every year our bankers help more than 15,000 Australians achieve their dream of owning their first home. This scheme is a fantastic way of helping even more customers, allowing them to potentially save thousands of dollars on their mortgage.”

The scheme will provide 10,000 eligible Australians per year access to a home loan with a deposit of as little as 5%. To implement the scheme, the NHFIC will contract with a panel of selected lenders rather than having direct contact with borrowers.

Before offering the guaranteed loans, lenders will need to update their internal systems and train front-line lending staff on how to apply the scheme eligibility criteria alongside regular considerations, such as loan serviceability.

The NHFIC has communicated key considerations in its selection of lender partners includes the loan products on offer, including interest rates and other fees, as well as the quality of the customer experience.

According to Baird, NAB is the only major to have a special rate for first homebuyers, which is currently 2.88% fixed for two years. The major bank also emphasised it will not charge eligible customers higher interest rates than equivalent customers outside of the scheme.

“We see this appointment as a great endorsement of NAB’s home loan offering and our support of Australians looking to buy their own home for the first time,” said Baird.

Before the scheme is live in the new year, customers are able to check their potential eligibility on the NHFIC website.

RBNZ Says Financial System Vulnerabilities Remain Elevated

Financial system vulnerabilities remain elevated and more effort is required to ensure that the system remains resilient over the longer-term, Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr says in releasing the November Financial Stability Report.

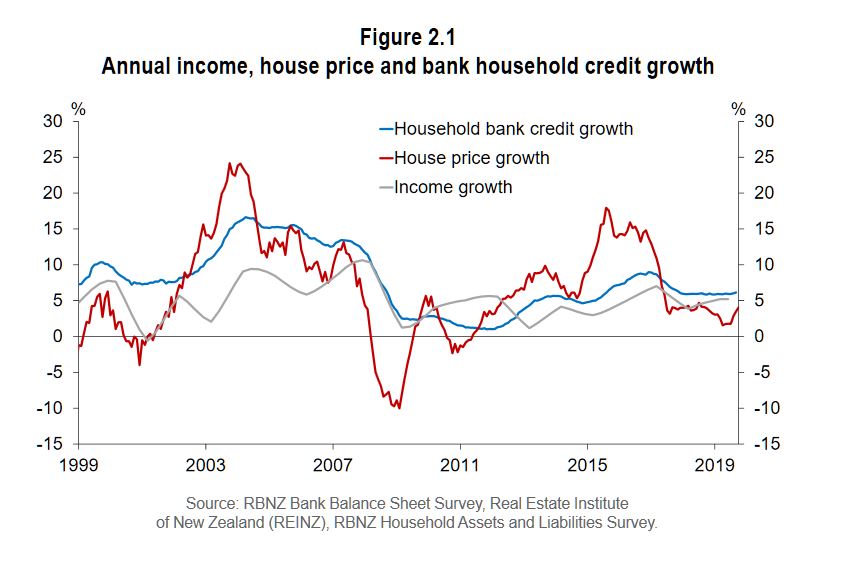

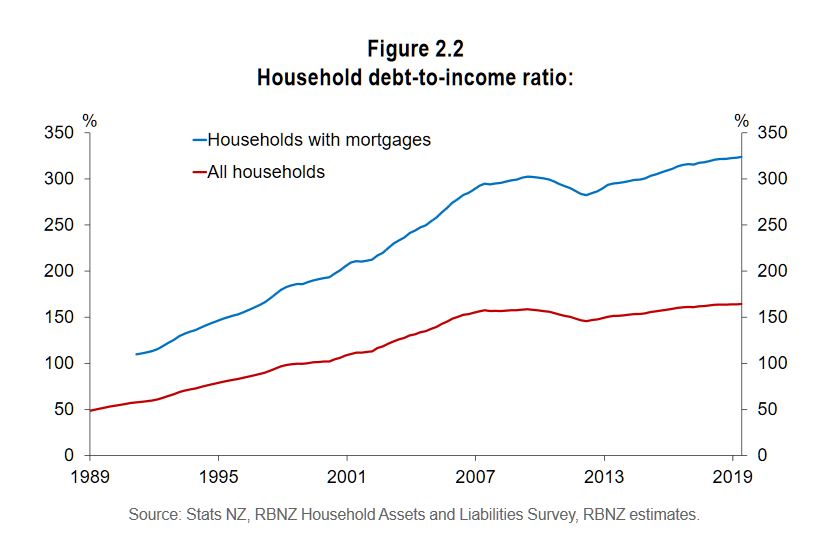

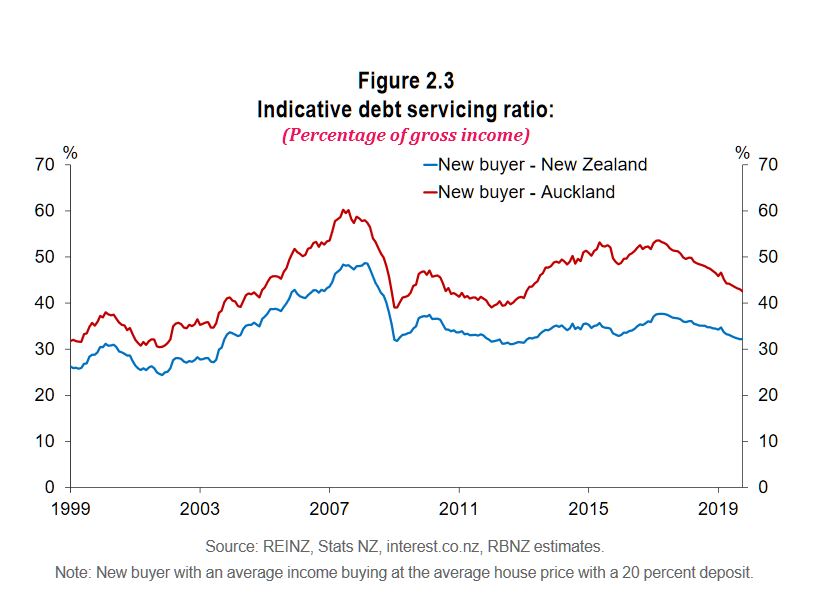

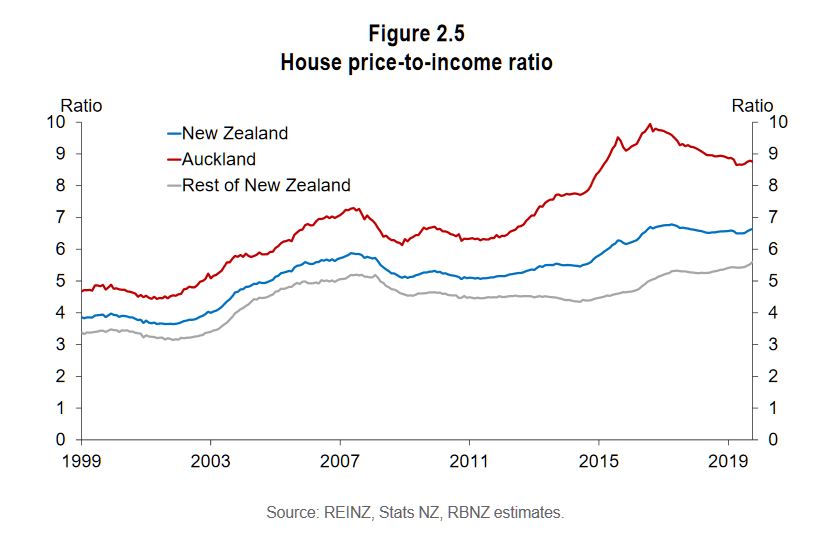

International risks to the financial system have increased. Global growth has slowed amid continued uncertainty about the outlook for world trade. This has resulted in reductions in long-term interest rates to historic lows, including in New Zealand. While necessary to maintain near-term inflation and employment objectives, prolonged low interest rates can promote excess debt and investment risk-taking, and overheat asset prices, Mr Orr says.

Mr Orr noted that the Reserve Bank’s Loan-to-Value Ratio (LVR) restrictions have been successful in reducing the more excessive household mortgage lending, thereby improving the resilience of banks to a significant deterioration in economic conditions.

But, there remains the risk that prolonged low interest rates could lead to a resurgence in higher-risk lending. As such, we have decided to leave the LVR restrictions at current levels at this point in time.

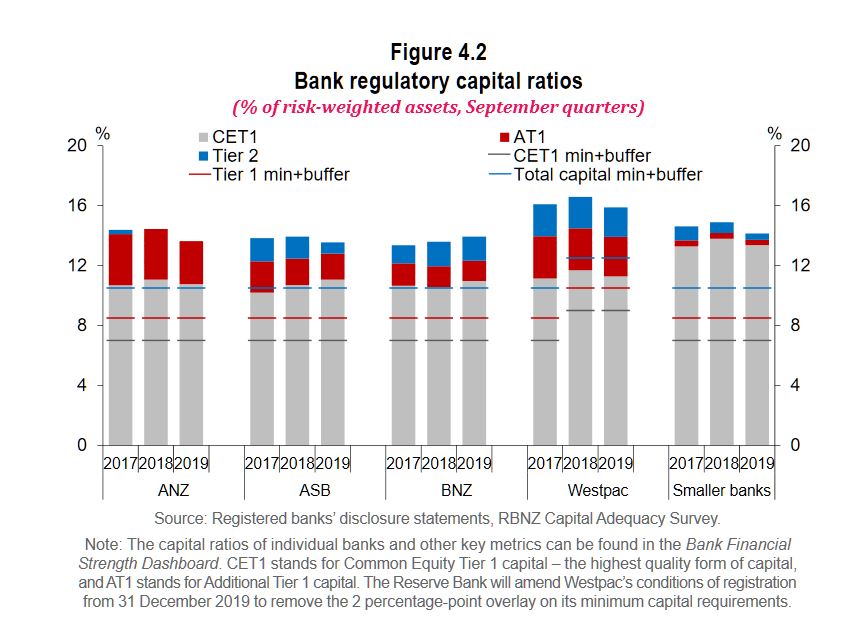

Mr Orr says the Reserve Bank is committed to bolstering the long-term resilience of the financial system. “Strong bank capital buffers are key to enabling banks to absorb losses and continue operating when faced with unexpected developments. The Reserve Bank has proposed increasing these buffers further with final decisions on the Capital Review proposals to be announced on 5 December.”

Deputy Governor Geoff Bascand says good governance and robust risk management processes within financial institutions are important to maintain long term resilience. Our recent reviews of banks and life insurers, and the number of recent breaches in key regulatory requirements, reinforces the need for financial institutions to improve their behaviour.

“We are engaging with industry to ensure that they strengthen their own assurance processes and controls. We have also reviewed our own supervisory strategy and will be taking a more intensive approach, which will involve greater scrutiny of institutions’ compliance,” Mr Bascand says.

“Some life insurers have low solvency buffers over minimum requirements. Recent falls in long-term interest rates are putting further pressure on solvency ratios for some of these insurers. Affected insurers are preparing plans to increase solvency ratios and are subject to enhanced supervisory engagement. This highlights the need for insurers to maintain strong buffers, and insurer solvency requirements will be reviewed alongside an upcoming review of the Insurance (Prudential Supervision) Act.”

RBA On Unconventional Monetary Policy

Governor Philip Lowe spoke at the Australian Economists Dinner last night. In many ways, little new here, but the RBA thinks the zero bounds cash rate is 0.25%, and QE is an option, but only in a crisis. “There may come a point where QE could help promote our collective welfare, but we are not at that point and I don’t expect us to get there”.

He said: As I discussed in the Sir Leslie Melville lecture at the ANU a month ago, low interest rates are not a temporary phenomenon. Rather, they are likely to be with us for some time and are the result of some powerful global factors that are affecting interest rates everywhere.[1]

Given this assessment, it is not surprising that there is a lot of discussion internationally about the use of so-called ‘unconventional’ monetary policies. People are rightly asking: if interest rates are going to stay low and be constrained by a lower bound, what other monetary policy options are there?

I have been part of these international discussions through chairing the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel. Last month, the Committee published a report titled: ‘Unconventional Monetary Policy Tools: a Cross-country Analysis’.[2] The report reviews the experience with the use of unconventional policy tools and discusses how these tools can be used by central banks to achieve their objectives. If you are interested in these issues and have not looked at the report, I encourage you to do so.

This evening I would like to summarise some key observations of the report and then explore how those observations might be applied to Australia.

The CGFS Report – the ‘Unconventional’ Policy Tools

The report discusses four unconventional policy tools.

The term ‘unconventional’ monetary policy has now become the conventional shorthand for a wide range of policies, although I am not sure it is the best terminology. I say this because most of these tools have always been in the toolkit of central banks and have been used in one way or another in the past. What has been unconventional over recent times is the way these tools have been used.

Negative interest rates

The first of the four tools discussed in the report is negative policy rates.

This is one tool that is truly unconventional.

Prior to the financial crisis, it was widely thought that zero was the lower bound for the policy interest rate – so it was common to talk about the ‘ZLB’, or the zero lower bound. It was thought that if interest rates went below zero, people would hold their savings in banknotes rather than be charged by their bank to deposit their money.

But zero has not turned out to be the constraint that it was once thought to be. So we now talk about the ELB – the effective lower bound – not the ZLB. While countries with negative interest rates have seen some shift to banknotes, it has been on a limited scale only. This reflects the use of bank deposits for making transactions and the fact that most banks in countries with negative interest rates have set a floor of zero on retail deposit rates. These banks have judged that it doesn’t make sense, either commercially or politically, to charge households and small businesses negative interest rates on their deposits.

It is worth pointing out that negative policy interest rates have largely been a European phenomenon. Policy interest rates have been negative in the euro area, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. Rates have been lowest in Switzerland, at minus ¾ per cent (Graph 1). The only country outside of Europe that has had negative policy interest rates is Japan, but even there it is only a very small share of bank reserves at the Bank of Japan that earns a negative rate, at minus 0.1 per cent.

Extended liquidity operations

The second unconventional policy discussed in the report is the extended use of central bank liquidity operations.

In response to the financial crisis, many central banks made significant changes to their normal market operations to deal with strains in financial markets that were impairing the supply of credit to the economy.

While the specifics differ across countries, the changes to market operations included: expanding the range of collateral accepted; providing much larger amounts of liquidity; extending the maturity of liquidity operations; increasing the range of eligible counterparties; and providing funding to banks at below the cost that was then prevailing in highly stressed markets, sometimes on the condition that the banks provide credit to businesses and households.

This graph shows the size of the extended liquidity operations of the major central banks (Graph 2). The biggest operations were during the crisis period of 2008 and 2009, with significant liquidity support also being provided in 2011 and 2012 to support bank lending during the European sovereign debt crisis.

It is worth recalling that during these periods of stress, banks had become very nervous about their access to liquidity. This, in turn, made them nervous about lending to others, making the possibility of a severe credit crunch very real. By providing financial institutions with greater confidence about their own access to liquidity, central banks were able to support the supply of credit to the economy. The CGFS report recognises that there were some side-effects of doing this, but the strong conclusion of the report is that these measures eased liquidity strains in highly stressed bank funding markets and helped restore monetary transmission channels to the broader economy.

Asset purchases – quantitative easing

The third policy tool discussed in the report is the outright purchase of assets from the private sector, paying for those assets by creating central bank reserves – also known as quantitative easing or QE.

These asset purchases were on an unprecedented scale and led to very large expansions of central bank balance sheets (Graph 3). Before the financial crisis, the major central banks owned securities equivalent to around 5 per cent of GDP. In recent years, this has risen to nearly 30 per cent. This is a very large change.

As part of their QE programs, central banks bought a wide range of assets, but the main asset purchased was government securities. Central banks now hold nearly 30 per cent of government securities on issue, which is equivalent to around 20 per cent of GDP. The largest purchases have been made by the Bank of Japan, which holds almost 50 per cent of Japanese government bonds on issue.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve also bought large quantities of agency securities backed by the US government. Elsewhere, central banks bought private securities such as covered bank bonds, corporate bonds and commercial paper. And the Bank of Japan bought equities via exchange traded funds (ETFs) and real estate investment trusts.

The precise motivations for these asset purchase programs varied across countries, but a common motivation was to lower risk-free interest rates out along the term spectrum, well beyond the short-term policy rate. Buying government bonds was seen as reinforcing policy rate cuts and/or acting as a substitute for further reductions in the policy rate once it was at its lower bound. The expectation was that lower risk-free rates would flow through to most interest rates in the economy, boost asset prices and push down the exchange rate.

A related motivation for buying government securities was to reinforce market expectations that policy rates were going to stay low for a long time. This ‘signalling channel’ added to the downward pressure on long-term bond yields.

Another motivation in some countries was addressing problems in specific markets. In the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve purchased government-backed agency securities to support mortgage markets. And the Bank of England purchased commercial paper to ease highly stressed conditions in corporate credit markets.

Finally, the expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet through money creation should, in theory, have stimulatory effects through the so-called ‘portfolio balance channel’. The idea here is that as the central bank purchases securities with bank reserves, investors seek to rebalance their portfolios, and in so doing push up other asset prices and lower risk premiums for borrowers. It is difficult, though, to isolate this effect from the other channels I just spoke about.

Forward guidance

The fourth policy response was forward guidance.

This took two forms: calendar based and state based. Under calendar-based guidance, the central bank makes an explicit commitment not to increase interest rates until a certain point in time. Under state-based guidance, the central bank says it will not increase rates until specific economic conditions are met. We have seen examples of both in practice. Some central banks also have provided forward guidance regarding their asset purchase programs.

A primary motivation of forward guidance is to reinforce the central bank’s commitment to low interest rates. A related motivation is to provide greater clarity about the central bank’s reaction function and strategy in unusual times. The experience has mainly been positive, with the guidance helping to reduce uncertainty. There are, however, some examples where a change in guidance caused market volatility. The ‘taper tantrum’ in the United States in 2013 is an example of this.

Some Observations

Before I discuss the relevance of all this to Australia, I would like to make three broad observations, drawing on the report as well as my own reading of the evidence.

The first is that there is strong evidence that the various liquidity support measures and targeted interventions in stressed markets were successful in calming things down and supporting the economy.

When markets broke down and became dysfunctional, the actions of central banks helped stabilise the situation and helped avoid a damaging gridlock in the financial system. They also helped contain risk premiums in highly stressed markets. It is also worth pointing out that many of the measures to support liquidity were successfully unwound once the job was done – so they proved to be temporary, rather than a permanent intervention.

The CGFS report also documents the positive effects of some of the other unconventional measures. In general, though, I find this evidence less compelling. These various measures certainly pushed down long-term yields and provided monetary stimulus in the depths of the crisis when it was needed. But these extraordinary measures have continued way past the crisis period. In some countries, asset purchases have yet to be unwound and it remains unclear when, and even if, this will happen. So a full evaluation is not yet possible.

This brings me to my second general observation. And that is that there have been some side-effects of the various unconventional measures. I will touch on a few of these that the CGFS report discusses.

The first is that the extensive use of unconventional monetary tools can change the incentives of others in the system, perhaps in an unhelpful way.

It is possible that the willingness of a central bank to provide liquidity reduces the incentive for financial institutions to hold their own adequate buffers, making episodes of stress more likely in the future.[3] It is also possible that the willingness of a central bank to use its full range of policy instruments might create an inaction bias by other policymakers, either the prudential regulators or the fiscal authorities. If this were the case, it could lead to an over-reliance on monetary policy.

A second side-effect is the impact on bank lending and the efficient allocation of resources. Persistently low or negative interest rates and a flattening of the yield curve can damage bank profitability, leading to less capacity to lend. In some countries, there are concerns that low interest rates allow less-productive (zombie) firms to survive. There are also financial stability risks that can come from low interest rates boosting asset prices (and perhaps borrowing) at a time of weak economic growth.

A third side-effect is a possible blurring of the lines between monetary and fiscal policy. If the central bank is buying large amounts of government debt at zero interest rates, this could be seen as money-financed government spending. In some circumstances, this could damage the credibility of a country’s institutional arrangements and create political tensions. Political tensions can also arise if the central bank’s asset purchases are seen to disproportionality benefit banks and wealthy people, at the expense of the person in the street. This perception has arisen in some countries despite the strong evidence that the various monetary measures supported both jobs and income growth and thereby helped the entire community.

These are all side-effects we need to take seriously.

The third general observation is that experience suggests that a package of measures works best, with clear communication that enhances credibility. Exactly what that package looks like varies from country to country and depends upon the specific circumstances. But clear communication from the central bank about its objectives and its approach is always important.

The report also notes that there may be better solutions than monetary policy to solving the problems of the day. It reminds us that when there are problems on the supply-side of the economy, the use of structural and fiscal policies will sometimes be the better approach. We need to remember that monetary policy cannot drive longer-term growth, but that there are other arms of public policy than can sustainably promote both investment and growth.

Application to Australia

I would now like to turn to what this all implies for us in Australia.

I will make five sets of observations.

The first is that the Reserve Bank has long had flexible market operations that allow us to ensure adequate liquidity in Australian financial markets. We have used this flexibility in the past, particularly during the global financial crisis, and we are prepared to use it again in periods of stress if necessary.[4]

At the moment, though, Australia’s financial markets are operating normally and our financial institutions are able to access funding on reasonable terms. In any given currency, the Australian banks can raise funds at the same price as other similarly rated financial institutions around the world, and markets are not stressed. So there is no need to change our normal market operations to do anything unconventional here. Having said that, if markets were to become dysfunctional, you can be reassured by the fact that we have both the capacity and willingness to respond. But this is not the situation we are currently in. Things are operating normally.

The second observation is that negative interest rates in Australia are extraordinarily unlikely.

We are not in the same situation that has been faced in Europe and Japan. Our growth prospects are stronger, our banking system is in much better shape, our demographic profile is better and we have not had a period of deflation. So we are in a much stronger position.

More broadly, though, having examined the international evidence, it is not clear that the experience with negative interest rates has been a success. While negative rates have put downward pressure on exchange rates and long-term bond yields, they have come with other effects too. It has become increasingly apparent that negative rates create strains in parts of the banking system that can impair the ability of some banks to provide credit. Negative interest rates also create problems for pension funds that need to fund long-term liabilities. In addition, there is evidence that they can encourage households to save more and spend less, especially when people are concerned about the possibility of lower income in retirement. A move to negative interest rates can also damage confidence in the general economic outlook and make people more cautious.

Given these considerations, it is not surprising that some analysts now talk about the ‘reversal interest rate’ – that is, the interest rate at which lower rates become contractionary, rather than expansionary.[5] While we take the possibility of a reversal rate seriously, I am confident that here, in Australia, we are still a fair way from it. Conventional monetary policy is still working in Australia and we see the evidence of this in the exchange rate, in asset prices and in the boost to aggregate household disposable income.

My third observation is that we have no appetite to undertake outright purchases of private sector assets as part of a QE program.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that there is no sign of dysfunction in our capital markets that would warrant the Reserve Bank stepping in. The second is that the purchase of private assets by the central bank, financed through money creation, represents a significant intervention by a public sector entity into private markets. It comes with a whole range of complicated governance issues and would insert the Reserve Bank very directly into decisions about resource allocation in the economy. While there are some scenarios where such intervention might be considered, those scenarios are not on our radar screen.

My fourth point is that if – and it is important to emphasise the word if – the Reserve Bank were to undertake a program of quantitative easing, we would purchase government bonds, and we would do so in the secondary market. An important advantage in buying government bonds over other assets is that the risk-free interest rate affects all asset prices and interest rates in the economy. So it gets into all the corners of the financial system, unlike interventions in just one specific private asset market.

If we were to move in this direction, it would be with the intention of lowering risk-free interest rates along the yield curve. As with the international experience, this would work through two channels. The first is the direct price impact of buying government bonds, which lowers their yields. And the second is through market expectations or a signalling effect, with the bond purchases reinforcing the credibility of the Reserve Bank’s commitment to keep the cash rate low for an extended period.

Currently, the government bond yield curve sits around 20 basis points above the overnight indexed swaps (OIS) curve, which represents the market’s average expectation of the future monetary policy rate (Graph 4). Purchasing government securities could compress this differential and could also flatten the OIS curve through the expectations effect I just mentioned. A lower term premium would lower borrowing costs for both governments and private borrowers, and would bring the benefits that come with that. An exchange rate effect could also be expected.

Our current thinking is that QE becomes an option to be considered at a cash rate of 0.25 per cent, but not before that. At a cash rate of 0.25 per cent, the interest rate paid on surplus balances at the Reserve Bank would already be at zero given the corridor system we operate. So from that perspective, we would, at that point, be dealing with zero interest rates.[6]

My fifth, and final, point is that the threshold for undertaking QE in Australia has not been reached, and I don’t expect it to be reached in the near future.

In my view, there is not a smooth continuum running from interest rate reductions to quantitative easing. It is a bigger step to engage in money-financed asset purchases by the central bank than it is to cut interest rates.

There are, however, circumstances where QE could help. The international experience is that in stressed market conditions, the central bank can help stabilise the situation by buying government securities. That experience also suggests that QE does put additional downward pressure on both interest rates and the exchange rate. In considering the case for QE, we would need to balance these positive effects with possible side-effects.

We would also need to consider the effects on market functioning. We are conscious that government securities play a crucial role as collateral in some of our financial markets. Given the limited supply of government debt on issue, the Reserve Bank and APRA have already had to put in place special liquidity arrangements for the banking system. We are also conscious that the Australian government’s fiscal position means that the gross stock of government debt is projected to decline relative to the size of the economy over the years ahead. These considerations are not impediments to undertaking QE, but we would need to take them into account.

It is a reasonable question to ask what might be the threshold to undertake QE in Australia.

It is difficult to be precise, but QE would be considered if there were an accumulation of evidence that, over the medium term, we were unlikely to achieve our objectives. In particular, if we were moving away from, rather than towards, our goals for both full employment and inflation, the purchase of government securities would be on the agenda of the Board. In this world, I would hope other public policy options were also on the country’s agenda.

At the moment, though, we are expecting progress towards our goals over the next couple of years and the cash rate is still above the level at which we would consider buying government securities. So QE is not on our agenda at this point in time.

It is important to remember that the economy is benefiting from the already low level of interest rates, recent tax cuts, ongoing spending on infrastructure, the upswing in housing prices in some markets and a brighter outlook for the resources sector. Given the significant reductions in interest rates over the past six months and the long and variable lags, the Board has seen it as appropriate to hold the cash rate steady as it assesses the growth momentum both here and elsewhere around the world. The Board is also committed to maintaining interest rates at low levels until it is confident that inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range.

The central scenario for the Australian economy remains for economic growth to pick up from here, to reach around 3 per cent in 2021. This pick-up in growth should see a reduction in the unemployment rate and a lift in inflation. So we are expecting things to be moving in the right direction, although only gradually.

The Board continues to discuss what role it can play in ensuring that this progress takes place and how it might be accelerated. It recognises the benefits that would come from faster progress, but it also recognises the limitations of monetary policy and the importance of keeping a medium-term perspective squarely focused on maximising the economic welfare of the people of Australia. There may come a point where QE could help promote our collective welfare, but we are not at that point and I don’t expect us to get there.

A Positive View Of The Future Of Cash!

Dr. Johannes Beermann, Member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank spoke about the future of cash at the Payment Asia Summit. Shenzen, China.

As the member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank responsible for cash management, I arguably very much represent what many of you may consider the “”old world of payments””. A world in which there is limited space for innovation and progress. A world that is generally high in risk but low in reward. That is what is often claimed, at least.

In giving you my European and my German perspective, in particular, let me tell you: this case is not as straightforward as it may seem. In Germany and the euro area at large, the circulation of cash remains on the rise. The Bundesbank has issued more than half of the value of euro banknotes currently in circulation. Handling and distributing cash is a major operational task performed by national central banks in the euro area – particularly the Bundesbank. This also means that we need to continue investing in our cash infrastructure.

Cash serves various economic functions – making payments is just one of them. Our estimates suggest that roughly one out of ten banknotes issued by the Bundesbank is used for making payments in Germany. This limits the size of the pie that is up for grabs by the various non-cash payment alternatives.

Let us focus on cash as a payment instrument nonetheless. Usage of cash as a means of payment is declining – this is true both internationally and in Germany. But the level of cash usage is still high in many countries – and especially so in Germany. There may be less cash around, but we are far from being cashless. So why is it that, as of yet, physical cash has not disappeared beneath the waves in the vast ocean of digital payment methods?

2. Cash as an independent means of payment

In my view, this has to do with the special features that cash offers. We regularly monitor payment behaviour in Germany to understand households’ motives for using particular forms of payment over others. Protection against financial loss, personal privacy and a clear overview of spending are crucial features that households expect from payment instruments. Cash scores favourably in all of these areas, according to our surveys. My interpretation of these results: German households value independence – and physical cash offers three unique forms of independence, which distinguishes it from digital payment systems.

First, independence from one’s socio-economic background. Cash is tactile and does not require any technical equipment. The use of cash is easily understood across the generational divide. It is this haptic nature of cash, which, in my view, is an important element of strengthening financial inclusion. Ensuring access to cash may be particularly relevant in rural areas with insufficient banking or technological infrastructures. Cash is, in that sense, also a means of safeguarding social cohesion.

Second, independence from technological ecosystems. Given the still fragmented payments landscape in Europe, cash currently remains the one truly universal means of payment when it comes to P2P transactions in the euro area. Fintech companies are shaking up the traditional banking system in Europe. These companies can often leverage their global reach and huge customer base. This may bring benefits for consumers, for instance regarding cross-border payments. But it also means that customers are becoming locked into particular payment ecosystems. Cash offers an easy way out, at least for certain transactions.

Third, independence from social control and data collection. As legal tender, cash is fully backed by the domestic central bank. Cash is the obvious choice of payment method when it comes to personal privacy. This strengthens individual freedom. At the end of the day, digital payment systems work by using personal data. Collecting data is not harmful per se. But in the age of Big Data, collecting detailed data means obtaining valuable information which, in turn, makes it possible to construct patterns of individual behaviour. From a consumer protection point of view, the question arises as to how much information is necessary to carry out a particular transaction. From an economic point of view, personal data may be seen as an additional source of transaction costs to be factored in when comparing the underlying cost structures of different payment methods.

3. Retailing – the source of future transformations?

Payment methods tend to evolve in stages. For example, the adoption of mobile payment solutions is typically preceded by the widespread use of credit and debit cards. This is the case in Germany, where contactless payments have just started to catch on. China, on the other hand, seems to be a case in its own right. A comparative study in China and Germany supports this. The evidence reported there for the year 2017 suggests that cash and debit card payments account for the bulk of German retailers’ revenue. Mobile-based payment solutions did not play a noticeable role at that time. The reverse picture emerges for Chinese consumers in major cities. Third-party mobile payment providers clearly dominate here, having leapfrogged debit and credit card payments.

Payment habits in China are still in a state of flux as payment technologies continue to evolve. Seamless payment methods are on the rise. These methods essentially try to counter the “pain of paying” with a physical smile. To what extent similar shopping experiences are becoming popular in Germany remains to be seen. There are serious concerns surrounding data protection, and these would need to be alleviated first. In my view, the transition towards a society with less cash has to be driven by the user and not the supplier. It appears that, at least in Germany, consumers value the existing diversity of payment options. Cash continues to be an important part of this. In the bank-centred financial system in Germany, commercial banks are a major actor in the provision of a payment infrastructure that can cater for both cash and its digital alternatives.

Retailing in Germany is transforming, too. On the one hand, German retailers are increasingly turning to Chinese providers of mobile payment solutions, with a particular view to increasing sales to Chinese tourists. On the other hand, retailers have also increased the scope of their activities by closing the cash cycle in Germany. Nowadays, more and more shops are providing basic banking services for their customers such as cash withdrawals and deposits at the counters. To me, this shows that the transformation of the payments landscape is anything but complete.

4 CBDC as a cash substitute?

In the digital era, it should not be surprising that central banks, too, are discussing the potential merits and drawbacks of digital forms of a central bank currency (CBDC). There are currently many operational issues relating to CBDC that remain unresolved. This pertains, for example, to the technology implemented. Blockchains and the underlying distributed ledger technology seem promising, and central banks are open to them in principle. There are several potential use cases in settlement and payment systems, for instance, which are worth exploring further. But handling and safely storing vast amounts of data does not necessarily require distributed ledgers. We need to understand the underlying technologies better in terms of operational risk.

Also, the exact set-up of a CBDC needs to be thought through as the specifications may determine the potential effects. Broadly speaking, there are two conceivable variants of a CBDC. The wholesale type restricts access to CBDC to selected financial market participants for a specific purpose. The retail type, on the other hand, could grant domestic or even non-domestic non-banks access to CBDC on a wide scale.

The wholesale variant may be seen as an improvement on existing structures in terms of processing securities trading and foreign exchange transactions, but it would have little or no effect on monetary policy. The retail variant, however, could potentially mean a paradigm shift in the economic relationships between households, commercial banks and central banks that have evolved to date. uch a fundamental shift is not free of risks, and it requires careful consideration.

There is also the question of how strong households’ appetite for such a form of CBDC would actually be. This user perspective should not be left out in the discussion.

We need to see matters in perspective. After all, many of these debates have been fuelled by the plans announced by the Libra consortium. To me, what this shows, first and foremost, is the need to offer fast and cost-efficient systems for cross-border payments. We should go one step at a time. There are already several innovative market solutions that have the potential to be transformed into an efficient pan-European digital payment solution. In addition SEPA instant credit transfers could serve as a basis for pan-European payment solutions. We should develop these systems further before contemplating further, more radical steps.

5. Conclusion

The old world of payments versus the new world. This story is not new. At the turn of the millennium, there was a strong admiration for what was referred to as the new economy in Germany. New economy was a term used to describe internet start-ups which often relied on little physical capital to generate, at times, staggering market valuations. This was in contrast to the old economy. Think of brick-and-mortar car plants with, in some cases, considerable overheads. At this point, we can say that “”the new has become a bit old and the old has become a bit new””. Economic structures have integrated. The basic market forces still apply: the companies that survive are those that are competitive and offer a unique product. I view the world of payments in very much that spirit. To me, digital payments offer exciting prospects. But that does not necessarily imply the extinction of existing payment methods. It may very well actually increase the diversity of payment methods. Cash offers these unique forms of independence from social and electronic networks, which suggests to me that it will continue to enjoy great popularity in the euro area.

The RBA has a new brain

MARTIN stands for “Macroeconomic Relationships for Targeting Inflation”, or perhaps merely for “Martin Place” which is the location of the Reserve Bank’s headquarters in Sydney. Via The Conversation.

It’s the bank’s new computer model of the Australian economy, made up of 147 equations working in concert. Some are quite simple, such as how global oil prices affect domestic petrol prices, whereas others are more complex, such as how a rise in the unemployment rate affects household spending.

Unveiled in August in a discussion paper entitled “MARTIN has its place”, the model is available for use by analysts outside the bank for whom it can serve as something of a guide as to what the bank might be thinking.

It provides useful insights into what the bank will do next, after it has cut its cash rate as close to zero as possible and needs to stimulate the economy further.

It’s a topic Governor Philip Lowe will expand on tonight in a landmark speech to business economists in Sydney.

What’s MARTIN, what’s a model?

Economists use models like drivers use maps – to take a large and complicated country and simplify it to its essential ingredients in the hopes of providing a useful guide to navigating it.

A map doesn’t tell you everything about a route – that would be hard to come to grips with – but it highlights important features or paths you should watch for. Models do the same – simplifying the complex Australian economy into the paths that matter.

But instead of breaking Australia down into rivers and roads, or cities and states like a map might do, MARTIN divides the Australian economy into different sectors such as households, firms and the government with the 147 equations describing the ways they interlink with each other.

This map is principally designed for two purposes.

- The first is forecasting. Every three months the bank looks inside its crystal ball to try and divine how the economy will evolve in the years to come. MARTIN has become a key input into that process.

- The second use is the ability to run “what if” simulations to see how the economy would react in different scenarios. For example, what would happen if the price of iron ore crashed tomorrow, or what would be the impact if the government ramped up its spending on infrastructure?

What does MARTIN say about quantitative easing?

MARTIN will have been put to work pondering the implications of deploying so-called “quantitative easing” after the Reserve Bank’s cash rate gets too low to cut.

Quantitative easing involves the Reserve Bank buying financial assets, such as government or mortgage bonds, in order to continue to supply money to the economy after its cash rate has fallen to zero.

I have used MARTIN to model three different scenarios for quantitative easing in the Australian economy.

The first is what would happen if quantitative easing isn’t used at all.

The second is what would happen if the bank started a modest quantitative easing program in early 2020 lasting around a year.

The third is what would happen if the bank commenced an aggressive quantitative easing program to simulate the economy for 18 months.

I assume the bank would purchase assets in a similar manner to how the US conducted quantitative easing after the global financial crisis, buying bonds to lower interest rates on two year and ten year government securities.

MARTIN says quantitative easing would have two major effects on the economy. First, it would lower the cost of borrowing for Australian businesses. They would be expected to increase investment as more projects become viable as the interest rates they were charged fell.

Second, the lower rate structure would weaken the Australian dollar by as much as 5 US cents. A cheaper dollar would make our exports more competitive and make foreign imports more expensive.

MARTIN thinks it could work

MARTIN predicts quantitative easing would boost manufacturing, agriculture and mining exports relative to where they would be without it.

The depreciation would also encourage Australian households to spend more on local goods and less on what would be dearer imports. This should lead to higher wages, increased household incomes and spending, and improved economic growth.

In fact, MARTIN predicts that, by boosting economic growth, quantitative easing would actually lead to higher interest rates as inflation returns to the Reserve Bank’s target, allowing interest rates to return to more normal levels.

Combining these two effects, MARTIN suggests a large quantitative easing program would reduce unemployment by 0.3 percentage points, equivalent to 40,000 extra jobs, and boost wages across the economy.

The output of any model is only as good as the information and data that are fed into it, but the output of MARTIN is why more and more economists expect the bank to quantitatively ease in the new year. Its brain says it should work.

Author: Isaac Gross, Lecturer, Monash University

US bank regulators lower capital requirements for the largest US banks

On 19 November, the US Federal Reserve, the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation approved a final capital rule for the largest US banks that requires them to adopt the standardized approach for counterparty credit risk (SACCR).

The rule must be adopted by those US banks which are mandated to use the Basel III advanced approaches (i.e., advanced internal ratings-based); other US banks may voluntarily adopt it. The advanced approaches banks include the eight US global systemically important banks: Bank of America, The Bank Of New York Mellon, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase & Co, Morgan Stanley State Street Corporation, and Wells Fargo & Company, as well as Capital One, Northern Trust Corporation, PNC Financial Services Group, and U.S. Bancorp. Many of these entities are also benefitting from the Fed’s Repo operations, which are designed to provide additional liquidity.

Moody’s says as originally proposed, SACCR would have resulted in a modest increase in risk-based capital requirements for the largest US banks but a modest decline in their leverage ratio requirements. However, in the final rule US regulators made several revisions to the original proposal which we expect will reduce both capital requirements, a credit negative.

The final rule is effective on 1 April 2020, with a mandatory compliance date of 1 January 2022. In 2014 the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision adopted SACCR as an amendment to the Basel III framework and in October

2018 US regulators proposed requiring the largest US banks to use SACCR for calculating their derivatives exposure amounts. SACCR is a more risk-sensitive approach to risk-weighting counterparty exposures than the current method and also revises certain calculations related to cleared derivatives exposures, including the measurement of off-balance-sheet exposures related to derivatives included in the denominator of the supplementary (i.e., Basel III) leverage ratio (SLR).

In the final rule, US regulators have made certain revisions to the original proposal, including reducing capital requirements for derivative contracts with commercial end-user counterparties and allowing for the exclusion of client initial margin on centrally cleared derivatives held by a bank on behalf of its clients from the SLR denominator.

Regulators explained that the reduction in capital requirements for exposures to commercial end-users is consistent with congressional

and other regulatory actions intended to mitigate the effect of post-crisis derivatives reforms on the ability of such counterparties to manage risks. Additionally, the exclusion of client initial margin on centrally cleared derivatives is consistent with the G20 mandate to establish policies that encourage the use of central clearing. The revisions may also prevent cross jurisdictional regulatory arbitrage because they would align the US with regulations in the UK and Europe on this matter, which are key jurisdictions where many of the largest US banks operate.

Nevertheless, a reduction in capital requirements would allow firms to increase their capital payouts or add incremental risk in other businesses without needing to hold more capital. Regulators estimate that the final rule would result, on average, in an approximately 9% decrease in large US banks’ calculated exposure amount for derivatives contracts and a 4% decrease in their standardized riskweighted assets associated with derivative exposures. The final rule would also lead to an increase of approximately 37 basis points (on average) in banks’ reported SLRs. If all 12 US banks subject to this rule were to maintain their SLRs at current levels instead of letting them rise as they would under the final rule, it would lead to the removal of approximately $55 billion in Tier 1 capital from the US

banking system.

Regulators also estimated that the final rule would lead to changes in individual banks’ SLRs, ranging from a decrease of five basis points to an increase of 85 basis points. Regulators did not identify which bank would receive the largest benefit. Moody’s estimate that if one of the six largest US banks is the beneficiary of an 85-basis-point increase in its SLR and the SLR was previously its binding capital constraint, allowing it to return to its shareholders an amount of capital equal to the entire benefit, it would lead to a reduction of between $9 billion and $25 billion in capital at just one bank.

In addition, on 19 November, US banking regulators published a final rule that amends the supplementary leverage ratio calculation to exclude custody bank holdings of central bank deposits. The change will only apply to The Bank of New York Mellon, State Street Corporation and Northern Trust Corporation.

Although the amended calculation is credit negative because it will allow custody banks to reduce capital and still meet one of their regulatory requirements, the practical effect is limited because other regulatory capital measures, specifically post-stress capital requirements, constrain the banks.

The final rule reflects the implementation of Section 402 of the 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA). Although EGRRCPA primarily aims to reduce regional and community banks’ regulatory burden, it also identifies central bank deposits held by custody banks as unique. In particular, custody banks maintain significant cash deposits with central banks to manage client cash fluctuations linked to custody and fiduciary accounts. Typically, these client cash positions are funds awaiting distribution or investment, but they can spike significantly in times of stress when custodial clients liquidate securities.

Under the final rule, only the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank or central banks of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member countries that have been assigned a zero risk weight under regulatory capital rules are considered qualifying central banks. The rule also defines a custody bank as any US depository institution holding company with assets under custody to total assets of greater than 30:1. This ratio precludes other large custody providers also subject to the supplementary leverage ratio, such as JPMorgan Chase & Co., from excluding central back deposits in their capital calculation, because unlike the three qualifying firms they are not predominantly engaged in custody and asset servicing.

Looked at in isolation, the final rule would allow BNY Mellon, State Street and Northern Trust to reduce their Tier 1 capital by roughly $8 billion in aggregate – a significant 17% reduction – and still maintain the same supplementary leverage ratios. However, that ratio is just one of many capital requirements.

Indeed, regulators’ own analysis of the supplementary leverage ratio revisions, based on 2018 data, indicates that the final rule is unlikely to reduce Tier 1 capital for any of the three affected holding companies because other capital requirements are more binding.

Specifically, performance of the banks’ capital requirements under the Federal Reserve’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) process has constrained them.

The future course of the custody banks’ capital positions is not yet clear because other aspects of the US regulatory capital framework remain in flux. In particular, regulators are developing a stress capital buffer, which we expect will be incorporated into the CCAR process. On balance, we anticipate that the custody banks are likely to face a capital regime that is less restrictive, though the extent of capital relief is still uncertain.

However, the banks’ reduced supplementary leverage ratio requirement is an early indication of the likely trajectory.