The International Monetary Fund (IMF), Financial Stability Board (FSB) and Bank for International Settlements (BIS) released today a new publication on Elements of effective macroprudential policies. The document, which responds to a G20 request, takes stock of the international experience since the financial crisis in developing and implementing macroprudential policies and will be presented to the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Hangzhou.

Following the global financial crisis, many countries have introduced frameworks and tools aimed at limiting systemic risks that could otherwise disrupt the provision of financial services and damage the real economy. Such risks may build-up over time or arise from close linkages and the distribution of risk within the financial system.

Experience with macroprudential policy is growing, complemented by an increasing body of empirical research on the effectiveness of macroprudential tools. However, since the experience does not yet span a full financial cycle, the evidence remains tentative. “The wide range of institutional arrangements and policies being adopted across countries suggest that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’. Nonetheless, accumulated experience highlights – and this paper documents – a number of elements that have been found useful for macroprudential policy making,” the publication says. These include:

- A clear mandate that forms the basis for assigning responsibility for taking macroprudential policy decisions.

- Adequate institutional foundations for macroprudential policy frameworks. Many of the observed designs give the main mandate to an influential body with a broad view of the entire financial system.

- Well-defined objectives and powers that can foster the ability and willingness to act.

- Transparency and accountability mechanisms to establish legitimacy and create commitment to take action.

- Measures to promote cooperation and information-sharing between domestic authorities.

- A comprehensive framework for analysing and monitoring systemic risk as well as efforts to close information gaps.

- A broad range of policy tools to address systemic risk over time and from across the financial system.

- The ability to calibrate policy responses to risks, including by considering the costs and benefits, addressing any leakages, and evaluating responses. In financially integrated economies, this includes assessing potential cross-border effects.

The document includes some data on the use of macroprudential tools; illustrative examples of institutional models for macroprudential policymaking; and a brief summary of some of the empirical literature on the effectiveness of macroprudential tools.

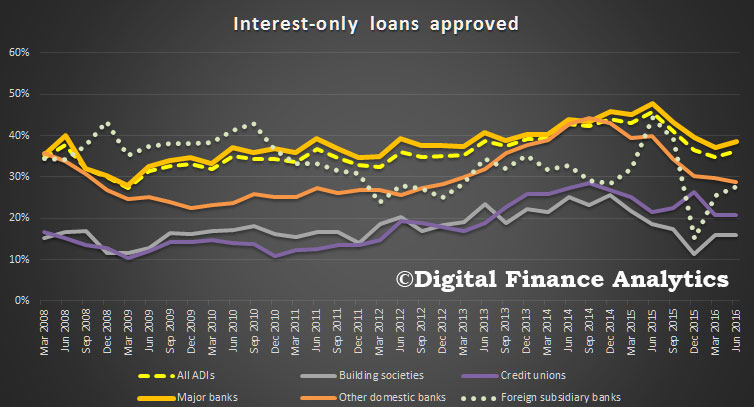

“Usage” counts the number of countries using the various instruments that comprise each group. Assuming that once a country introduces an instrument, it continues using it, the charts show usage of the various groups of instruments.

Institutional arrangements adopted by a country are shaped by country-specific circumstances, such as political and legal traditions, as well as prior choices on the regulatory architecture. While there can therefore be no “one size fits all” approach, in practice, there has been an increasing prevalence of models that assign the main macroprudential mandate to a well-identified authority, committee, or interagency body, generally with an important role of the central bank. While each of these models has pros and cons, any one model can be buttressed with additional safeguards and mechanisms.

- Model 1: The main macroprudential mandate is assigned to the central bank, with its Board or Governor making macroprudential decisions (as in the Czech Republic, Ireland, New Zealand and Singapore). This model is the prevalent choice where the central bank already concentrates the relevant regulatory and supervisory powers. Where regulatory and supervisory authorities are established outside the central bank, the assignment of the mandate to the central bank can be complemented by coordination mechanisms, such as a committee chaired by the central bank (as in Estonia and Portugal), information sharing agreements, or explicit powers assigned to the central bank to make recommendations to other bodies (as in Norway and Switzerland).

- Model 2: The main macroprudential mandate is assigned to a dedicated committee within the central bank structure (as in Malaysia and the UK). This setup creates dedicated objectives and decision-making structures for monetary and macroprudential policy where both policy functions are under the roof of the central bank, and can help counter the potential risks of dual mandates for the central bank (see further IMF 2013a). It also allows for separate regulatory and supervisory authorities and external experts to participate in the decision-making committee. This can foster an open discussion of trade-offs that brings to bear a range of perspectives and helps discipline the powers assigned to the central bank.

- Model 3: The main macroprudential mandate is assigned to an interagency committee outside the central bank, in order to coordinate policy action and facilitate information sharing and discussion of system-wide risk, with the central bank participating on the committee (as in France, Germany, Mexico, and the US). This model can accommodate a stronger role of the Ministry of Finance (MoF). Participation of the MoF can be useful to create political legitimacy and enable decision makers to consider policy choices in other fields, e.g. when cooperation of the fiscal authority is needed to mitigate systemic risk.