In a speech by Andrew Gracie, Executive Director of Resolution of the Bank of England, at the 21st Annual Risk USA Conference, he outlines some of the elements in the Too Big To Fail (TBTF) resolution agenda. The aim is to ensure that in the event that a global systemically important financial institution (G-SIFI) fails there is minimal interruption of the activities of a firm that are critical to the functioning of the broader financial system. And achieving that outcome without recourse to taxpayer bailouts, as public authorities were forced to during the crisis.

He says that progress in developing a new paradigm for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) has been impressive. Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions1 were agreed by G20 leaders around this time four years ago. Statutory regimes consistent with this standard are now in place in the US, EU and Japan – in fact in all but a handful of jurisdictions where G-SIBs are headquartered. Crisis Management Groups (CMGs) have been working on resolution plans for each of the G-SIBs. The authorities participating in the CMGs have committed at a senior level in a resolvability assessment process (RAP) to the resolution strategies emerging for each of the G-SIBs. These CMGs work towards identifying barriers to making resolution work and how these should be removed. Often these barriers are consistent across firms. Perhaps most notable is the requirement for loss absorbency – establishing a liability structure for G-SIBs that is consistent with bail-in, not bail-out. Again, there has been significant progress here. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) issued a consultation document2 on a minimum standard for Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) last November and is committed to producing a final standard ahead of the G20 summit next month in Antalya. This will be a major step on the road to ending “Too Big to Fail.”

He goes on to discuss the same TBTF agenda for other types of G-SIFIs, in particular central counterparties (CCPs). CCPs form a key part of the global financial landscape. They have become ever more important since the crisis. This will continue as mandatory central clearing is introduced around the world. These entities are an essential part of the international financial system, and need appropriate regulation and viable resolution paths in an event of failure, without causing a cascading crash. This aspect of the international financial markets and their control bears close watching.

Addressing the systemic risks associated with over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets is one of the reasons why G20 leaders introduced mandatory central clearing. People tell us that we have thus created in CCPs concentration risk and critical nodes. This is true in part, but we did this on the basis that in CCPs risks could be better recognised and identified, better managed and reduced via better netting. Nonetheless, as many before me have commented the largest CCPs are becoming increasingly systemic and interconnected such that their critical services could not stop suddenly without risk of wider contagion. Thus, not only do we have to ensure that the level of supervisory intensity matches the risks, something my supervisory colleagues are very focused on, we must also address the issue of what should happen if a CCP were to fail.

This is already widely recognised. So too is the need for an international solution to the questions that CCP recovery and resolution presents. The largest CCPs are systemically relevant at a global level, important for financial stability in multiple jurisdictions due to the nature of their business and the composition of their members and users. They serve multiple markets, having dozens of clearing members from different countries and clearing products in multiple currencies. A patch-work of approaches to recovery and resolution would risk regulatory arbitrage and competitive distortion and so, whilst the fiscal backstop against the unsuccessful resolution of a CCP is ultimately a national one, it is best that the answer on how to avoid this backstop ever being used is developed at a global level.

Fortunately, that work is already underway and CCP recovery and resolution forms an important part of the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) continuing agenda to end Too Big To Fail (TBTF). In October 2014 an Annex was added to the Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes to cover their application to Financial Market Infrastructures (FMIs). More recently, the FSB published its 2015 CCP workplan. As part of this, a group on financial market infrastructure (fmi CBCM), equivalent to the Cross-Border Crisis Management Group (CBCM) that I chair for banks, has been established within the FSB to take forward international work on CCP resolution. Authorities in a number of jurisdictions are responding to the need for effective resolution arrangements for CCPs, with legislative proposals expected in the EU, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong and elsewhere to add to existing regimes, including in the US under Title II of Dodd Frank. In the UK, the Bank of England has formal responsibility for the resolution of UK-incorporated CCPs. To aid us in drawing up resolution plans for UK CCPs, we have established the first Crisis Management Group for a CCP. We hope and expect it to be the first of many.

But work on CCP resolution needs to be seen in the broader context of financial reform:

The Committee on Payment and Market Infrastructures, along with the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (CPMI-IOSCO) is continuing its work on CCP resilience and recovery. Work is in train on stress testing, on loss allocation and on disclosure requirements, as well as on ensuring consistent application of the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs) which set regulatory expectations for CCPs at a global level. All of this is important not only in its own right, but also to provide the market – the users of CCPs – with the tools and incentives to monitor resilience and drive effective risk management in CCPs themselves. To encourage competition between CCPs on resilience, not cost.

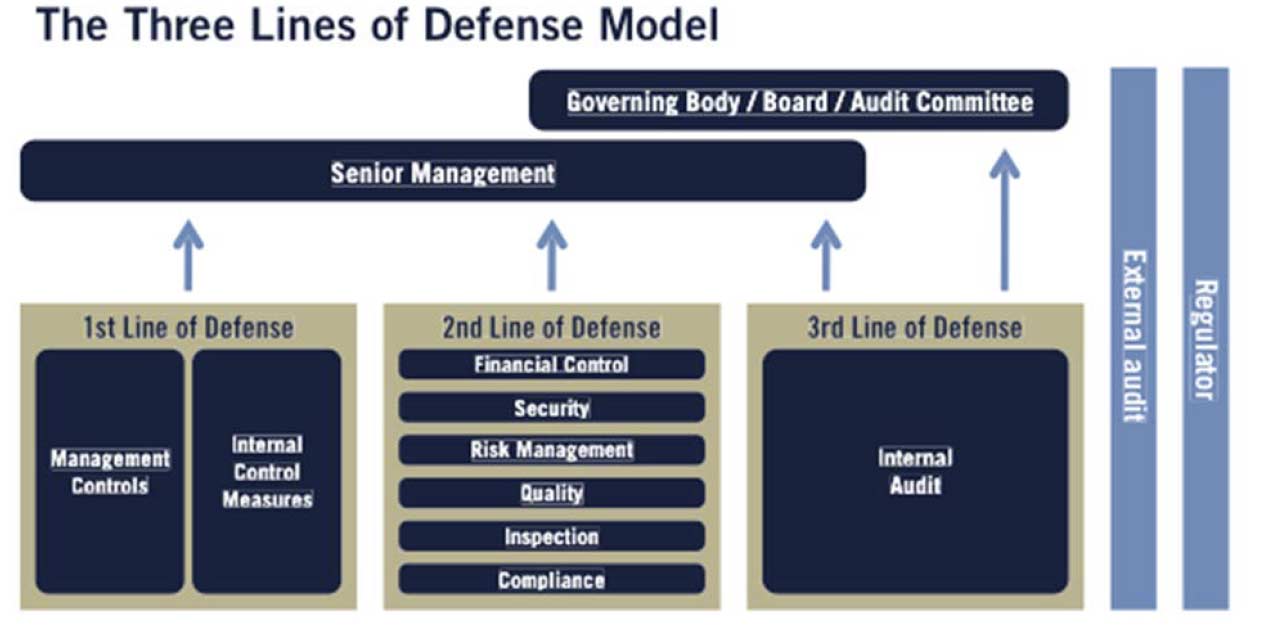

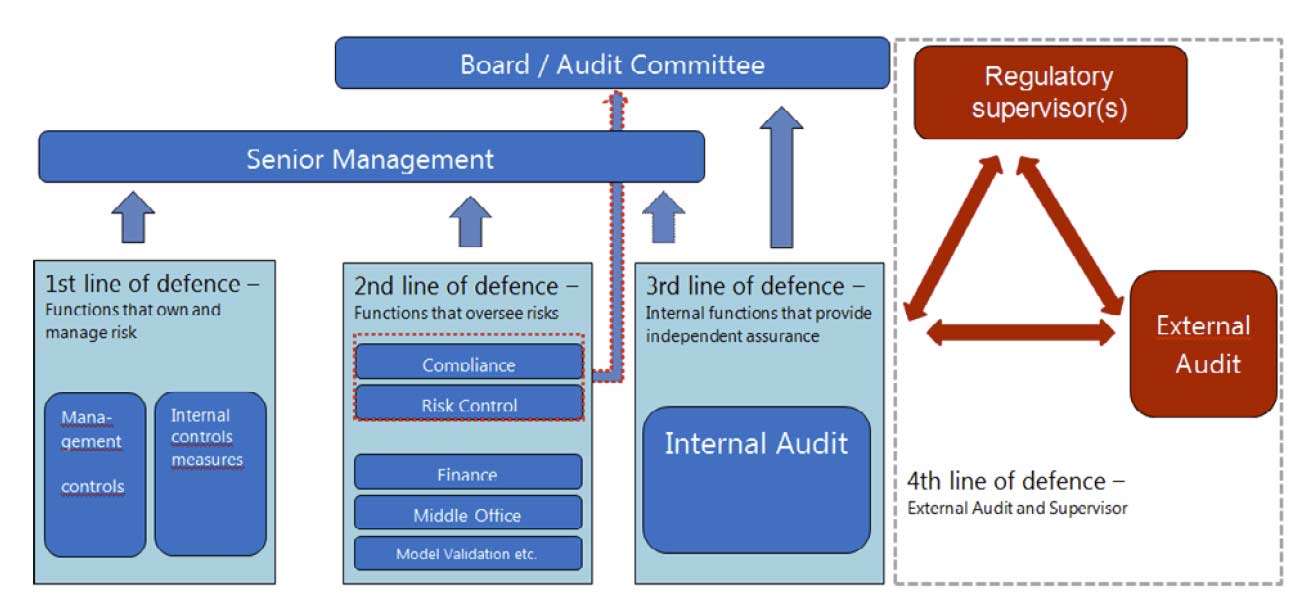

At the same time, the first line of defence for a CCP lies in the resilience of its members. Ongoing work to raise the prudential standards for banks on capital and liquidity, among other areas, should greatly reduce the risk of CCPs having to deal with a failing clearing member. And the progress I mentioned before on G-SIB resolution should help to ensure that, where a firm does fail, its payment and delivery obligations to the CCP continue to be met. I should add as an aside that there is more still to be done internationally in terms of removing technical and other obstacles to maintaining continuity of access to CCPs and other FMIs in the context of bank resolution. That continuity is not just essential to the bank in resolution but may also be critical for clients. If there is doubt about continued access to clearing services from a bank in resolution, clients may look to migrate rapidly to another provider. These issues around continuity and portability will be the subject of work within the FSB over the course of the coming year.

Together, these initiatives to improve the resilience and recovery arrangements for CCPs and their members will help to reduce the probability of CCP default. But while improvements to resilience are necessary they may not by themselves be sufficient. No institution is “fail safe”. Ultimately, we need to have a credible resolution approach for CCPs.

If we do, resolution should offer a continuing benefit in helping to incentivise recovery by removing expectations that the taxpayer will be compelled to step in. By contrast, if we do not have a credible regime in resolution, we run the risk of weakening the incentives both to manage a CCP prudently, as well as incentives for clearing members to contribute to a CCP’s recovery should it get into trouble. The benefits of resolution to market discipline and recovery are common to all financial institutions. But that is not the only insight from banks that is relevant to CCPs.

Before going too far in talking up the similarities, I should note – although it should go without saying – that CCPs are very different from their bank clearing members in many important respects, including their business models, legal structures and balance sheets. CCP recovery and resolution therefore poses some specific issues, some of which I will touch on today. However, at base there are principles that are common to the resolution of any systemically important institution.

Perhaps the most obvious similarity between the resolution of banks and CCPs is in the common objective: resolution should deliver continuity of critical economic functions without reliance on solvency support from taxpayers to achieve it. For that continuity to be achieved it is not enough that the financial losses of the institution are fully absorbed; the going-concern resources of the institution, or of any successor institution, must be restored to a sufficient level to command market confidence prior to any post-resolution restructuring or wind-down.

In the case of banks, this means that when a bank suffers losses eroding its going concern capital to the point where triggers for resolution are met, (i) it enters into resolution; (ii) its creditors are bailed in to recapitalise the firm; and (iii) this bail-in replicates what would have happened in a court-based commercial restructuring or insolvency. In other words, losses are allocated according to the creditor hierarchy but without the value destruction created by the hard stop of insolvency. This ensures that the resolution provides continuity and meets the safeguard that creditors are not worse off than in insolvency. While these are the essential elements of a resolution, they are likely to play out differently in the context of a CCP.

Intervention by a resolution authority, especially at a point where default management procedures have yet to be exhausted is action that cannot be taken lightly. Nor can the discretion of a resolution authority to deviate from the existing rules of the CCP be unbounded. Appropriate creditor safeguards are central to ensuring that an effective resolution regime does not unduly interfere with property rights or undermine its own value by introducing unnecessary uncertainty into a financial institution’s contractual relationships both in resolution and outside of it.

Perhaps the most fundamental safeguard to creditors in resolution is that the actions of the resolution authority will not leave them worse off than if the authority had not intervened and the firm had instead entered a liquidation proceeding. For the purposes of determining this No Creditor Worse Off protection, bank resolution takes an insolvency counterfactual; recognition that a failing bank that meets the conditions for resolution would in most likelihood lose its licence at that point if not resolved, thereby tipping it into insolvency (whether cash-flow, balance-sheet or both) if it was not there already. That insolvency counterfactual requires an ex post assessment of the value of assets and liabilities of the firm. That is no easy task but one that can, and has been, credibly undertaken.

For CCPs the task of assessing an insolvency counterfactual is likely to be harder still – particularly if it must rely upon a forecast of how the rest of the waterfall would have unfolded, the behaviour of the CCP’s participants and the movements of the markets in the days that would have followed if resolution had not taken place. A liquidation counterfactual must also confront the argument that the CCP would have protected itself from insolvency through full tear-up.

Given these valuation challenges, I suspect there will need to be careful further consideration given to the formulation and practical application of the NCWO safeguard; we must end up with a safeguard that is sufficiently certain and capable of estimation in advance that both creditors and resolution authorities are able to make sensible decisions before, during and after resolution.

With that, let me conclude by summing up some key points:

- CCP resolution is both a necessary and inevitable part of the overall post-crisis reform agenda to end Too Big to Fail. As private, profit-making enterprises CCPs must be allowed to fail, but, given their systemic importance, many will need to be allowed to do so in a manner that maintains the continuity of their critical functions.

- Having a credible resolution regime for Clearing Members is a big step forward in helping to reduce the risk of clearing member default and from that the risk of CCP failure.

- But reliance on successful resolution of members does not negate the need for CCP resolution arrangements to be capable of responding to both default and non-default losses emerging from both systemic and idiosyncratic shocks.

- In thinking about the underlying objectives and needs of a CCP resolution regime, there are many similarities to bank resolution and these should not be forgotten, but clearly there are many differences too and we need to recognise that.

- Effective resolution requires the ability to act promptly and before the point at which the chance of stabilising the CCP is lost. The resolution authority must have a variety of tools at its disposal to enable it to respond to the reason the CCP failed. It should be able to intervene in a timely and forward-looking way before the end of the waterfall – but incentives must be aligned and we want this to be set up in a way that promotes CCP resilience and makes recovery work.

- In order to continue a CCP’s critical services in resolution, there must be an ability both to cover the losses credibly in a failure scenario and to recapitalise the CCP’s going concern resources – i.e. its capital, margin and default fund. How we achieve this is something for FSB to address so that the shared interest in maintaining stability in the global financial system can be realised.