A new IMF working paper “Excessive Private Sector Leverage and Its Drivers: Evidence from Advanced Economies“, aims to provide a quantitative assessment of the gaps between actual and sustainable levels of debt and identifies the key factors that drive excessive borrowing.

They explain why high household debt – such as we have in Australia – should be a cause for concern. It seems to sum up the current state of play here, very well.

High private debt can have a substantial adverse impact on macroeconomic performance and stability. It hinders the ability of households to smooth consumption and affects investment of corporations. In addition, elevated debt levels can create vulnerabilities as well as amplify and transmit macroeconomic and asset price shocks throughout the economy. Excessive private debt increases the likelihood of a financial crisis, especially when it is driven by asset price bubbles fueled by lending. The subsequent deleveraging could be potentially disruptive for economic activity.

Long-term growth prospects deteriorate significantly following debt-related financial crises. Furthermore, the accelerated pace of private debt accumulation can lead to economic and financial instability, which often coincides with great risk-taking and poorly regulated and supervised financial sector. Finally, spillovers from private balance sheets to the public sector due to government interventions, either direct in the form of targeted programs for debt restructuring or indirect through the banking sector, weaken the fiscal position and increase interest rates. All the above factors may potentially compromise public debt sustainability.

They assess the extent of excessive leverage in advanced economies, and conclude that private sector debt overhang is relatively large, with significant heterogeneity across developed economies. Household excessive leverage is found to be higher in countries with lower interest rates and higher share of working population, but importantly also in countries with rising house prices and greater uncertainty as captured by unemployment. Corporate debt overhang is estimated to be higher in countries with lower profitability, stronger insolvency frameworks and absence of thin capitalization rules.

In assessing the situation, they make the point that using debt to income ratios alone, omits an important aspect of debt sustainability – the strength of the borrower’s balance sheet. Debt can be repaid not only from future income but also by selling assets; hence, solvency indicators, such as the debt to asset ratio, are widely used in debt sustainability analyses.

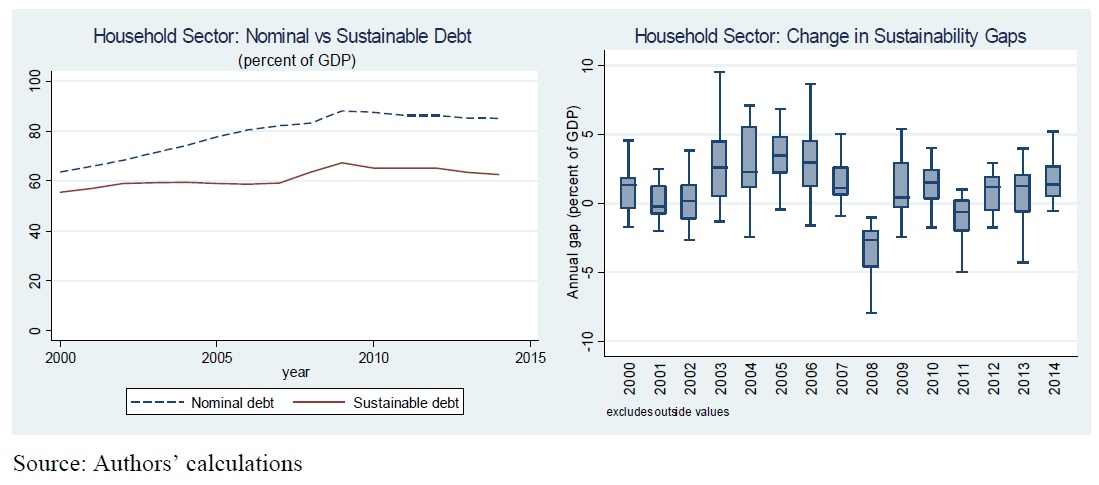

They apply a “deflated” approach to assessing debt, starting from a base year, and compare the subsequent growth. The sum of deflated financial and non-financial assets represents total notional assets. Similar to financial assets, deflated debt is obtained by adding debt transactions to the initial stock of debt. Deflated sustainable debt is then calculated as deflated debt in the initial year, increased by the change in notional assets and corrected for transitory changes in the nominal debt-to-asset ratio (which is assumed stationary). In other words, deflated debt is considered sustainable when it evolves with deflated assets. Excessive leverage is measured by the difference between the actual and sustainable debt.

The results from our empirical analysis suggest that in a number of advanced economies household and corporate debt has increased to levels that may not be sustainable. Most of the debt build-up took place before the financial crisis, but with a few exceptions, there has been little deleveraging in the post-crisis period. In a number of countries, the gap between actual and sustainable debt, calculated on the basis of notional assets continues to grow. The gaps are larger in the household sector; the borrowing behavior of non-financial corporations does not seem to have changed much on aggregate, although there is significant cross-country

heterogeneity.Drawing on the theoretical literature on household and corporate debt determinants and building on earlier empirical work, we try to identify the main drivers of excessive leverage. Most of the variables that have been found important in previous studies focusing on indebtedness, turn out to be significant in explaining the debt sustainability gaps as well. In particular, low interest rates and unemployment along with high house prices tend to be associated with larger gaps in the case of household. This implies that policymakers should pay attention to excessively low interest rates and inflated house prices to avoid imbalances that may ultimately pose risks to macroeconomic stability. While we find evidence for importance of institutions, the tax treatment of mortgage debt does not appear to be significant, although the latter could be due to difficult measurement issues. Still, this does not mean that there is no role for policies in containing leverage. For example, generous mortgage-related tax incentives that favor ownership over renting can induce excessive borrowing by households and boost asset prices which, as discussed above, are positively correlated with the sustainability gaps. Furthermore, such incentives have important distributional implications and can be costly in terms of foregone revenue for the budget.

In the case of non-financial corporations, profitability is a significant factor behind leveraging, while thin capitalization rules tend to reduce the debt overhang. Thin capitalization rules can be an effective instrument to limit excessive borrowing but they need to be well designed. In many countries such rules provide escape clauses that effectively limit them to related party debt, implying that these measures aim to reduce debt shifting, but do not deal effectively with the debt bias. Introducing a tax system based on allowance for corporate equity (ACE) would not only reduce the incentives to incur debt but would also stimulate investment as it is effectively a tax only on excess returns or rents. There is also some role for institutions because countries with stronger insolvency regimes are typically characterized by lower debt overhang.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.