The IMF concluding statement says Australia is transitioning from the mining boom with strong growth and relatively low unemployment, but has not been immune to symptoms of the “new mediocre”. Wage and price pressures are weak, underemployment has risen, and non-mining investment is yet to fully recover. Ensuring the return to full employment under weak global conditions will need continued accommodative monetary policy and quality infrastructure spending, which will also boost long term growth potential. A coordinated fiscal and monetary policy response may also be needed if large downside risks were to materialize. Prudential policies have helped reduce housing related risks, and efforts to strengthen financial sector resilience should continue.

Context

Australia’s economic performance has remained remarkably robust in comparison to other advanced economies despite lower commodity prices and the end of the mining investment boom. The resilience to the large shocks since 2011 reflects a flexible exchange rate acting as a shock absorber, an accommodative monetary policy stance, export orientation to the dynamic Asia region, flexible labor markets, relatively high population growth, and strong institutions.

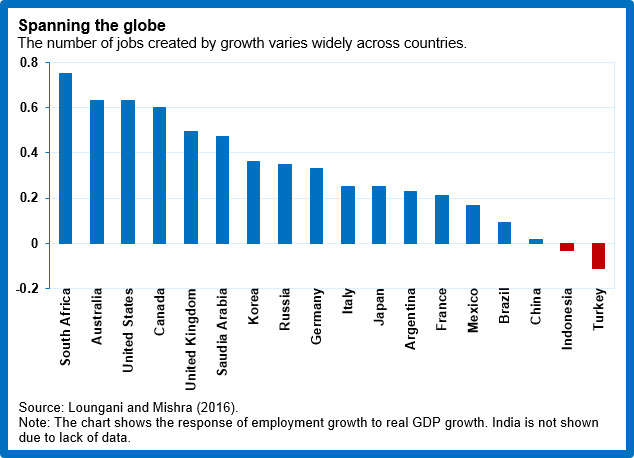

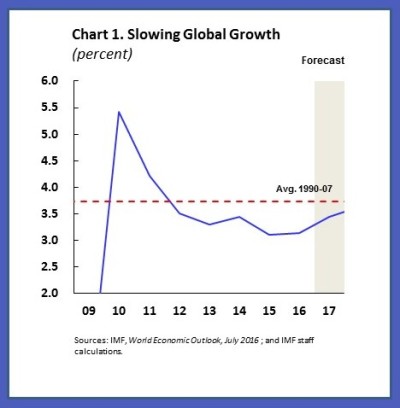

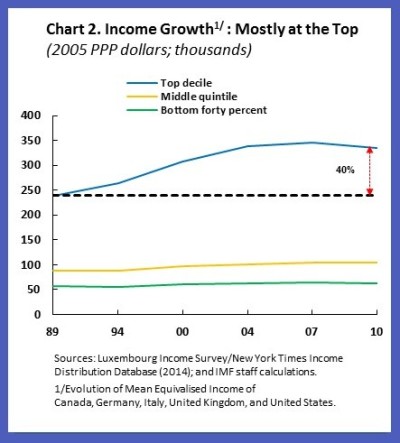

Still, Australia has been confronted with symptoms of the “new mediocre,” albeit to a lesser extent than in almost all other advanced economies. Growth has been lower since the global financial crisis (GFC), with much of the related decline in potential growth because of moderating population growth. As elsewhere, the recovery has fallen short of expectations in 2014-15, because of external and internal factors, including in non-mining business investment. While unemployment has remained relatively low, underemployment and longer-term unemployment have risen, and nominal wage growth and inflation have been weak.

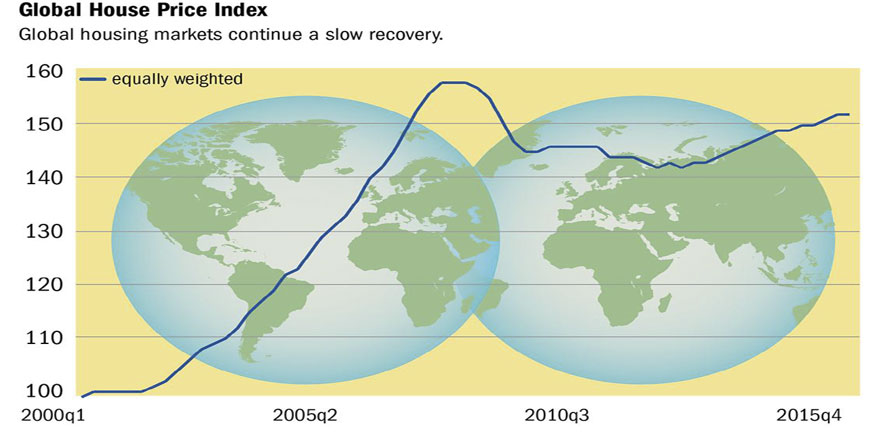

House prices and household debt ratios have risen further in the low-interest environment post-GFC, up from already high pre-crisis levels. Other macro-financial vulnerabilities relate to the perennial, sizeable net external liabilities, intermediated in part through the banking sector.

Recent Developments, Outlook and Risks

After a pickup in economic activity from mid-2015, Australia has advanced markedly in its recovery but experienced a downshift in inflation in early 2016. Annual growth has increased to over 3 percent, partly on account of temporary factors. Both headline and core inflation are now below the RBA’s 2 to 3 percent target range.

Economic slack has started to moderate, although the fall in the unemployment rate has likely overstated the improvement in labor markets. The underemployment rate—defined as the proportion of employed persons in the labor force seeking to work more hours—has risen, as some 80 percent of jobs created over the past year have been part-time jobs.

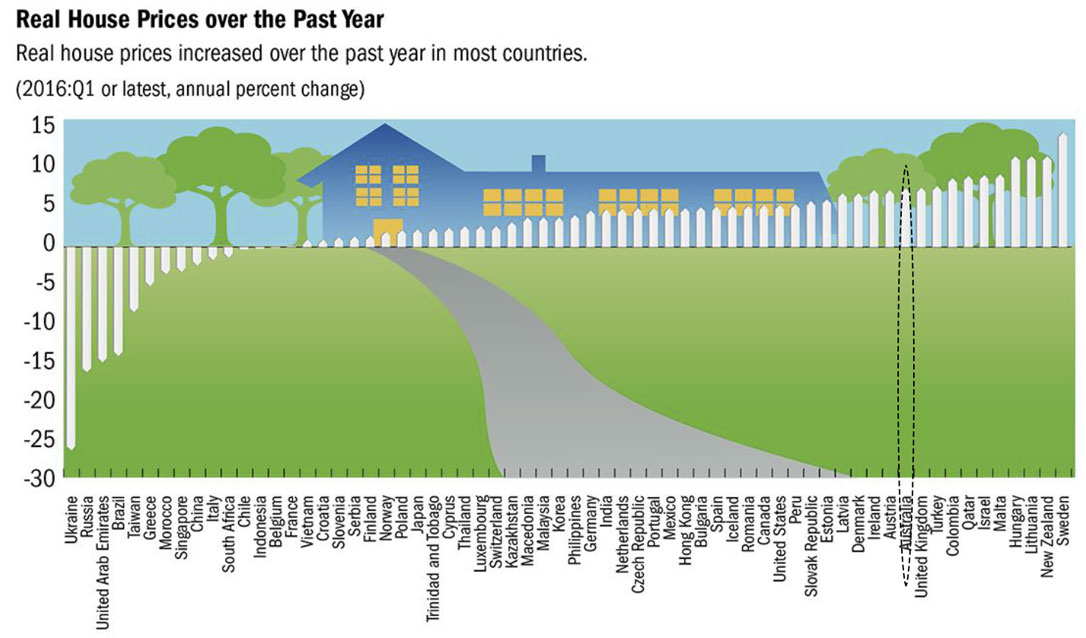

On the macro-financial side, prudential policies have resulted in a tentative stabilization of housing-related vulnerabilities. APRA’s prudential measures introduced in late 2014, including tighter lending standards focusing on debt serviceability, have improved the risk profile of new loans. Overall housing credit growth and market turnover have remained lower than last year. But with the declines in longer-term interest rates and continued strong demand, including from nonresidents, upward pressure on house prices has remained strong in some cities. While household debt has continued to be high, risks to banks and to household balance sheets are mitigated by the ongoing strong growth in deposits in mortgage offset accounts.

Banks’ balance sheets have become more resilient . APRA’s analysis suggests that, after raising capital, CET-1 capital ratios of Australian banks have, on a comparable basis, narrowly moved into the upper quartile of international peers (broadly in line with the Financial System Inquiry recommendation that banks’ capital positions be “unquestionably strong”). As banks prepare to meet net stable funding ratio requirements by 2018, the share of stable funding in their liabilities has already increased, including higher shares of domestic deposits and longer-term debt.

The baseline outlook is for a continued gradual recovery. After strong momentum, growth is expected to moderate somewhat over the next two years. The disinflation experienced in 2015-16 is expected to start reversing. On the macro-financial side, house price inflation is expected to realign with broader measures of nominal income. The accumulation of net external liabilities should slow in the absence of valuation effects.

The balance of risks has improved but is still tilted to the downside. On the upside, the momentum of the recovery could be stronger, as recent strong growth and terms-of-trade improvements could boost business confidence and unlock stronger business investment. On the downside, investment could be more subdued, as corporate profits could remain under pressure for longer. Consumption growth could turn lackluster if wage growth stayed low. On the external side, there are risks to global trade from rising populism and nationalism in large economies and from tighter and more volatile global financial conditions. A major concern is that external risks with a large impact, including a sharp growth slowdown in China, could interact with or even trigger domestic risks, especially a housing correction.

Policy Discussion

Australia’s transition following the end of the mining investment boom is well advanced but adequate policy support remains critical to secure the return to full employment in a fragile global environment and longer-term growth. The lack of significant price and wage pressures suggests persistent slack, which, if prolonged, risks hurting medium-term supply potential.

Monetary Policy

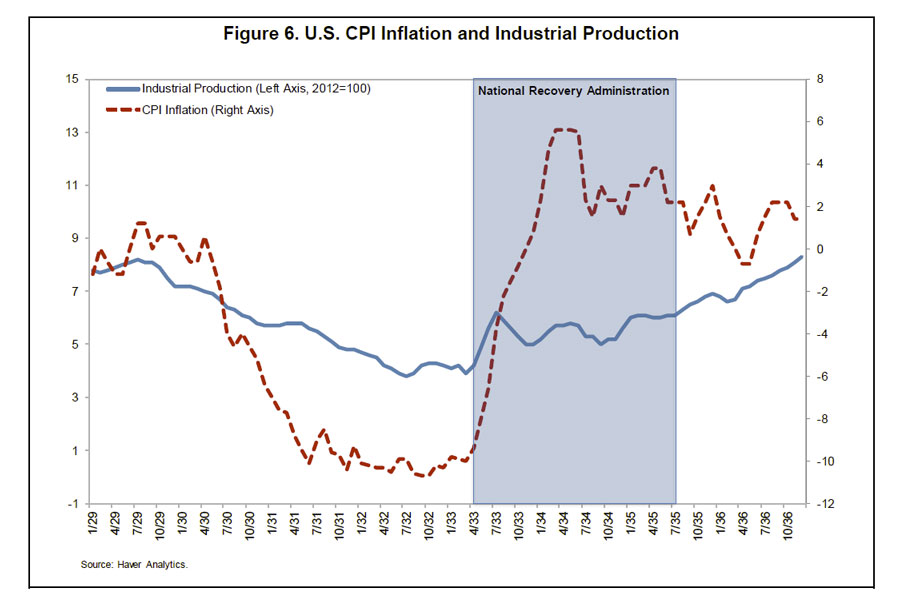

The monetary policy stance should remain accommodative in a still disinflationary global environment. While Australia’s low inflation is more recent than in most other advanced economies, policy decisions should remain predicated on the possibility that inflation may return into the target range later than expected, given international experience. In this regard, the RBA’s prompt monetary policy response to the lower-than-expected inflation in early 2016 has reinforced its commitment to the inflation targeting framework. Prudential measures to address housing-related risks have mitigated concerns about the impact on balance sheets and financial stability from lowering policy rates further. With the expected very gradual return of inflation into the target range, lengthening the forecast horizon in monetary policy statements could clarify the RBA’s expectations about the inflation path.

Fiscal Policy

Australia has fiscal space even though recent budget targets have been missed and debt has risen. Metrics such as the debt-to-GDP ratio suggest that there is fiscal space under both the baseline and economic stress scenarios. In IMF staff’s view, the worse-than-planned budget outcomes over the past few years have reflected the weaker-than-expected growth rather than policy easing. Forging ahead with consolidation would most likely have resulted in lower growth over that period.

The government appropriately plans to balance the budget over a 5-year horizon while making the expenditure composition more growth-friendly. The change in the expenditure composition focuses on supporting longer-term growth through spending on infrastructure and other measures supporting longer-term and inclusive growth, including measures to boost innovation and address youth unemployment.

In IMF staff’s view, the pace of targeted fiscal consolidation under the baseline should be more gradual and some of the growth-friendly spending should be ramped up.

- The May 2016 budget targets front-loaded fiscal consolidation, especially in FY2017/18 where the adjustment is penciled in at roughly 3/4 of a percentage point of GDP. Such an ambitious pace could be counterproductive in the current phase of the recovery. Australia has the fiscal space for undertaking more gradual consolidation to a balanced budget by FY2020/21, the target in the budget.

- While general government spending on infrastructure has increased in FY2016/17, this increase primarily reflects higher spending by states, not the Commonwealth. Indeed, capital spending is expected to increase by ½ of a percentage point of GDP in the current budget year, but these efforts are not expected to be sustained as spending is projected to level off in the next fiscal year and to decline thereafter. A more sustained, multi-year increase in spending on efficient infrastructure also at the Commonwealth level would be desirable, considering that Australia has infrastructure needs and fiscal space, the funding environment is favorable, and that the expected return to full employment is gradual. The boost to growth under these conditions should largely contain the impact of more gradual consolidation with higher infrastructure spending on the public debt-to-GDP ratio, provided that discipline in recurrent spending is maintained. If high-impact downside risks were to materialize, fiscal policy should support aggregate demand, as monetary policy could be constrained. Unlike in previous downturns, monetary policy may soon be constrained by the lower bound on nominal policy rates. Contingency plans and a pipeline of infrastructure projects would help in reducing the implementation lags involved in undertaking fiscal stimulus.

A long-term debt anchor could strengthen the current fiscal framework. It is a strength of the framework that it requires the Commonwealth government to report against a medium-term fiscal strategy based on “principles of sound fiscal management.” IMF staff recommends to consider augmenting the current medium-term budget balance anchor with a longer-term debt anchor. The latter would provide certainty about debt and fiscal policy in the future and, if implemented over a 5- to 10-year horizon, would be sufficiently flexible to allow for countercyclical support if needed.

Managing Macro-Financial Vulnerabilities

With more acute risks concentrated in a few specific housing market segments, policies should focus on further strengthening resilience to housing market and other shocks with macro-financial implications.

- With continued upside risk to house prices, APRA should stand ready to intensify targeted prudential measures, if investor and other risky lending or house price growth were to re-accelerate. However, the scope and extent of tightening need to be carefully calibrated, so as not to trigger a sharp correction.

- APRA should continue to actively encourage banks’ efforts to robustly anchor their capital position in “unquestionably strong” territory, given a highly concentrated banking sector where banks have similar business models.

- Treasury’s preparation of new legislation to further the regulatory reform agenda should continue to complete the implementation of the recommendations of the Financial System Inquiry, including on the crisis management toolkit and bank resolution. APRA should continue in its effort to implement prudential steps to strengthen the loss absorbing and recapitalization capacity of banks and introduce leverage ratios, in line with the international agenda.

The macro-financial resilience of the economy to housing market shocks could be enhanced through tax reform . The tax system provides households with incentives for leveraged real estate investment that likely amplifies housing cycles.

Keeping Up Productivity Growth

Maintaining high productivity growth rates may be challenging. Overall labor productivity growth in Australia has remained broadly stable over the 2000s. However, in some of the services sectors with a growing employment share, labor productivity growth has been weak, as has multifactor productivity growth more generally.

The government’s reform agenda appropriately focuses on fostering innovation and strengthening competition . It includes the government’s National Innovation and Science Agenda, which allocates $1.1 billion over four years to boost innovation and entrepreneurship in the high tech sector. We encourage its envisaged continuation and, if effective, its expansion. On competition, the measures recommended by the Harper Review would strengthen services sector competition and ultimately productivity. The process of implementation is underway, but will require extensive collaboration between the Commonwealth government and the governments of the States and Territories.

We welcome Australia’s intention to continue efforts toward further trade liberalization, both in regional and multilateral fora. Expanding access to service export markets could also strengthen services sector productivity in Australia and elsewhere, while the social safety net and active labor market policies would mitigate the cost to those who shoulder the burden of adjustment.