The Turnbull government’s lack of serious action on housing affordability is most obvious when one of its own MPs is calling it to account, as backbencher John Alexander did again on Monday.

Mr Alexander last year headed a government-dominated parliamentary inquiry on housing affordability that, after he’d been transferred to another inquiry, made no recommendations on housing affordability at all.

But that has not stopped the former tennis champ making a lot of noise on the subject himself. For that he should be commended.

Mr Alexander wants to keep house prices roughly where they are – what he calls “stability in the market” – but to tilt the market towards owner-occupiers rather than investors.

Well, that would be a start, but real affordability comes when house prices and wages stop diverging and start to move closer together. In an era of low inflation and low wages growth, that could take a very long time.

Among some of his more useful ideas there remains a real stinker that others, such as billionaire property developer Harry Triguboff, have raised in recent years – namely, allowing young Aussies to use their super savings to invest in their first home.

OECD warns of a ‘rout’ in house prices

That would help owner-occupiers to outbid investors, but pouring such a large amount of capital into the market would push prices even higher.

Mr Alexander told the ABC on Monday: “The most important thing … is to understand that property bought with super remains the property of your super. If you sell it, the money goes straight back into your super.

“… People aren’t getting into the market until 45, they retire at 65, then they cash in their super to pay out their house. So the money … has gone into an unassessable asset, so those people have full claim on the aged pension. They have actually used their super to buy their house.”

That sounds like a good argument, until you consider the economic context: household debt has never been higher, house prices have never been higher, and wage growth has never been slower.

In short, the super-into-housing argument comes with the standard financial product warning that ‘past performance does not guarantee future results’.

A wobbly asset class

The housing market in Australia has outperformed all other asset classes in the past two decades, but to suggest it can do so again is arguing against simple arithmetic.

Try these nonsensical arguments on a maths teacher sometime: ‘House prices can continue to outpace wages and inflation forever. Each year’s first home buyers can afford to spend a greater portion of their pay on housing. Interest rates will never rise.’

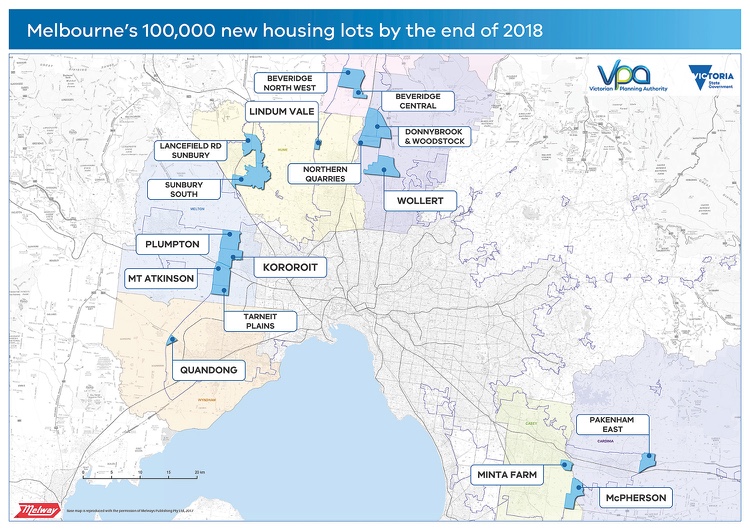

Alternatively, we can learn from the painful lesson being experienced right now in Perth, where stretched home valuations are on the decline (see chart below).

In the past 12 months, Perth house prices have fallen 5 per cent, while the ASX has risen 10.6 per cent – and that’s without counting reinvested dividends.

So a young, would-be home owner could have got themselves in quite a pickle if they’d been allowed to tip, say, $100,000 from their balanced super portfolio into the single home asset.

Their ‘super-owned’ deposit would be worth $5000 less, their home equity would be down $20,000 and a comparable super portfolio that tracked the share market would be up $11,000.

Net result: $36,000 behind. The leveraged gains of earlier years have become leveraged losses.

It’s true, of course, that in the past two decades you can find times when these numbers have been reversed.

But that was then. Young home buyers may not fully understand that now is not the time to be playing Russian roulette with super.

Superannuation fund managers are trained to maximise returns across a range of asset classes, which they trade in and out of as markets change. None would tip all of a saver’s super into a single dwelling.

There are plenty of sound ways to fix housing affordability. But at this time, more than ever, raiding super isn’t one of them.