Household Survey Data

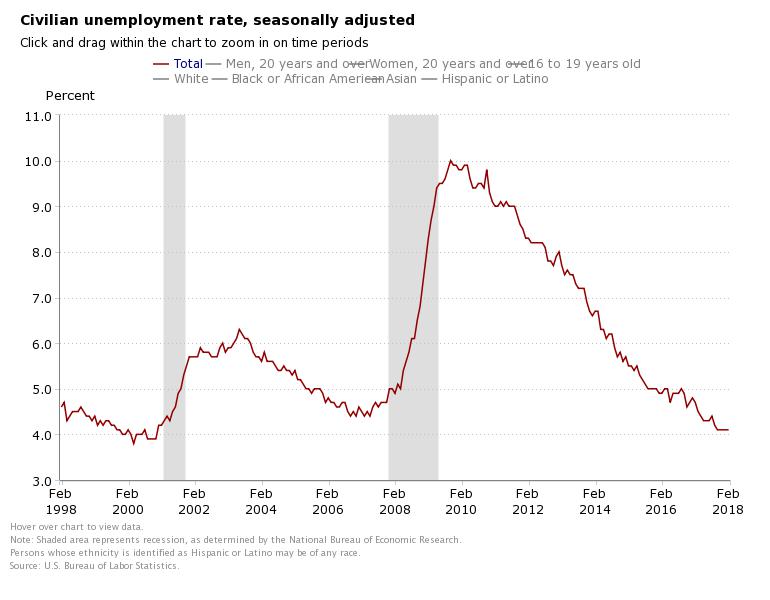

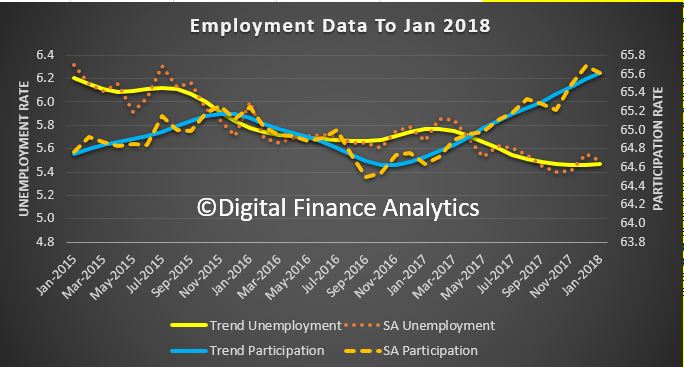

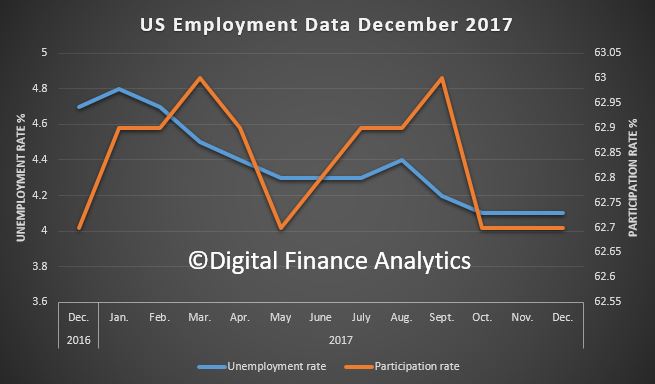

In February, the unemployment rate was 4.1 percent for the fifth consecutive month, and the number of unemployed persons was essentially unchanged at 6.7 million.

Among the major worker groups, the unemployment rate for Blacks declined to 6.9 percent in February, while the jobless rates for adult men (3.7 percent), adult women (3.8 percent), teenagers (14.4 percent), Whites (3.7 percent), Asians (2.9 percent), and Hispanics (4.9 percent) showed little change.

The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) was essentially unchanged at 1.4 million in February and accounted for 20.7 percent of the unemployed. Over the year, the number of long-term unemployed was down by 369,000.

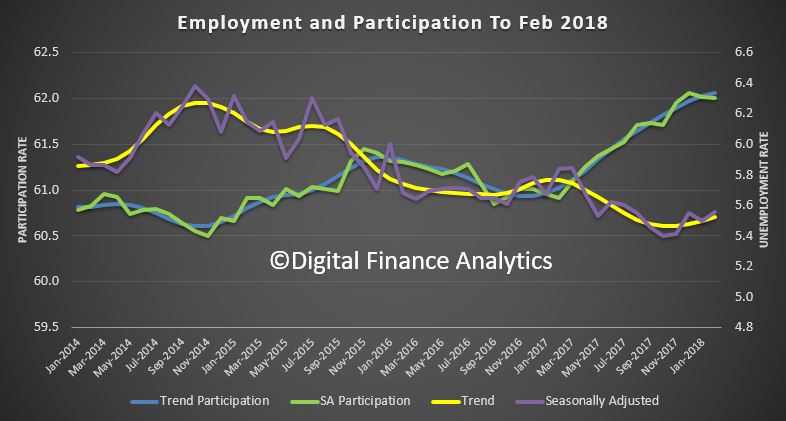

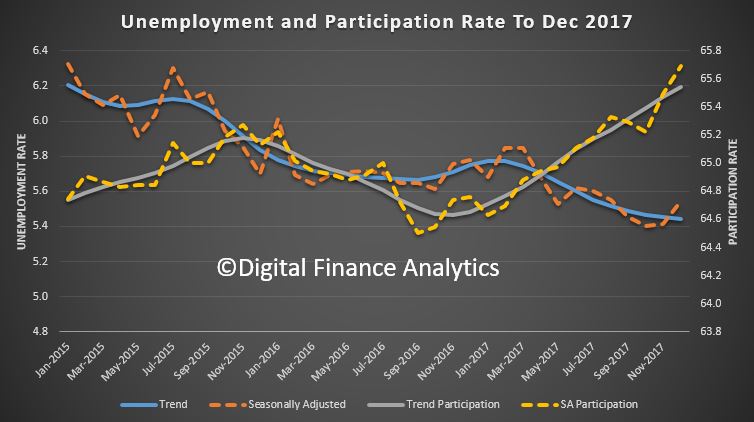

The civilian labor force rose by 806,000 in February. The labor force participation rate increased by 0.3 percentage point over the month to 63.0 percent but changed little over the year.

In February, total employment, as measured by the household survey, rose by 785,000. The employment-population ratio increased by 0.3 percentage point to 60.4 percent in February, following 4 months of little change.

The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons (sometimes referred to as involuntary part-time workers) was little changed at 5.2 million in February. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been cut or because they were unable to find full-time

jobs.

In February, 1.6 million persons were marginally attached to the labor force, little different from a year earlier. (The data are not seasonally adjusted.) These individuals were not in the labor force, wanted and were available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey.

Among the marginally attached, there were 373,000 discouraged workers in February, down by 149,000 from a year earlier. (The data are not seasonally adjusted.) Discouraged workers are persons not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them. The remaining 1.2 million persons marginally attached to the labor force in February had not searched for work for reasons such as school attendance or family responsibilities.

Establishment Survey Data

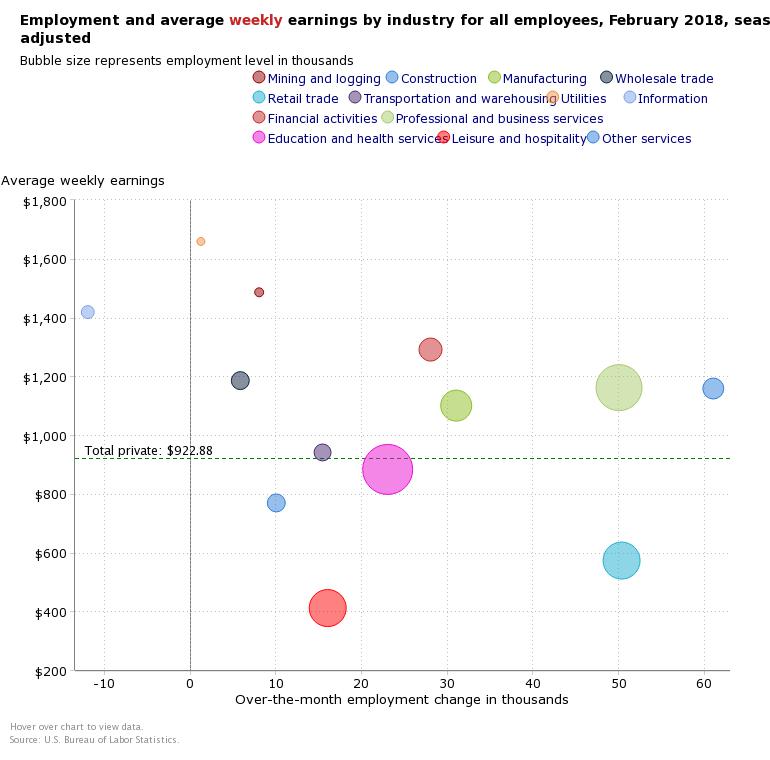

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 313,000 in February. Job gains occurred in construction, retail trade, professional and business services, manufacturing, financial activities, and mining.

In February, construction employment increased by 61,000, with gains in specialty trade contractors (+38,000) and construction of buildings (+16,000). Construction has added 185,000 jobs over the past 4 months.

Retail trade employment increased by 50,000 over the month. Within the industry, employment rose in general merchandise stores (+18,000) and in clothing and clothing accessories stores (+15,000). However, over the past 4 months, which traditionally see the bulk of the holiday hiring and layoff, employment in these industries has changed little on net. Elsewhere in retail trade, building material and garden supply stores added jobs over the month (+10,000).

Employment in professional and business services increased by 50,000 in February and has risen by 495,000 over the year. Employment in temporary help services edged up over the month (+27,000).

Manufacturing added 31,000 jobs in February. Within the industry, employment rose in transportation equipment (+8,000), fabricated metal products (+6,000), machinery (+6,000), and primary metals (+4,000). Over the past year, manufacturing has added 224,000 jobs.

Financial activities added 28,000 jobs over the month, with gains in credit intermediation and related activities (+8,000); insurance carriers and related activities (+8,000); and securities, commodity contracts, and investments (+5,000). Over the year, financial activities has added 143,000 jobs.

Employment in mining rose by 9,000 in February, with most of the increase in support activities for mining (+7,000). Since a recent low in October 2016, mining has added 69,000 jobs.

Employment in health care continued to trend up in February (+19,000), with a gain of 9,000 in hospitals. Health care has added 290,000 jobs over the past year.

Employment in other major industries, including wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, information, leisure and hospitality, and government, showed little change over the month.

The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 0.1 hour to 34.5 hours in February. In manufacturing, the workweek increased by 0.2 hour to 41.0 hours, while overtime edged up by 0.1 hour to 3.6 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by 0.2 hour to 33.8 hours.

In February, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 4 cents to $26.75, following a 7-cent gain in January. Over the year, average hourly earnings have increased by 68 cents, or 2.6 percent. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees increased by 6 cents to $22.40 in February.

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for December was revised up from +160,000 to +175,000, and the change for January was revised up from +200,000 to +239,000. With these revisions, employment gains in December and January combined were 54,000 more than previously reported. (Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published

estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.) After revisions, job gains have averaged 242,000 over the last 3 months.