On 10 December, Deutsche Bank AG hosted an investor day following the announcement this summer of its more radical shift in strategy. Via Moody’s.

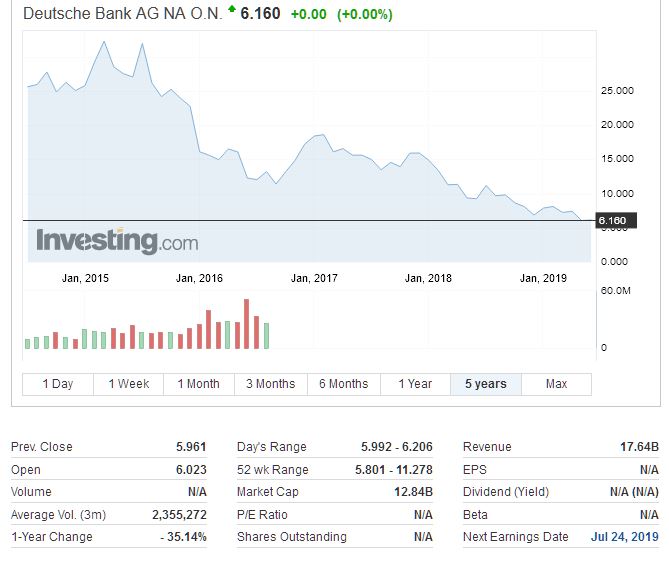

We see the bank as being on track to achieving the majority of the plan’s targets, in particular with regard to the proposed de-risking, downsizing and cost-cutting measures, while achievement of the revenue growth targets may prove more challenging. Continued fast and steady progress in achieving the new goals and repositioning DB’s business model will be important to maintaining its current credit strength, which we believe will continue to be supported by its clean balance sheet and solid capital and liquidity metrics during execution.

Within the bank’s capital release unit (CRU), its key wind-down unit, the bank expects risk-weighted assets (RWAs) to decline toward €52 billion by the end of 2019, down 28% year over year, while it expects leverage exposures to fall to €120 billion, a decline of 57% year over year. This includes the effect of DB’s transaction agreement with BNP Paribas on DB’s global prime finance and electronic equities business, supporting further swift de-risking and downsizing of the CRU, as well as help financing the group’s restructuring program out of its own financial resources. DB expects adjusted costs to be €21.5 billion in 2019, and reiterated its target of €19.5 billion of adjusted costs in 2020 and €17 billion in2021.

Notwithstanding continued strong credit-positive cost control, management also guided for lower revenue growth, largely owing to lower interest rates negatively affecting its private bank franchise. DB now expects group revenue to be around €24.5 billion by 2022, a slight reduction from the earlier €25 billion target. This includes a cumulative negative revenue effect of €1.2 billion during the restructuring period. However, DB has already initiated measures aimed at offsetting approximately two-thirds of this revenue strain. Sustained execution success will therefore rely on DB’s ability to rebuild and stabilize core bank revenue against the backdrop of the increasingly challenging macroeconomic environment.

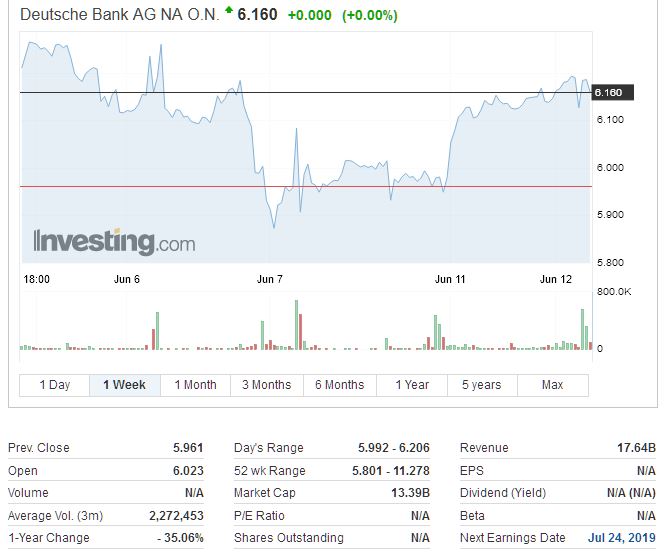

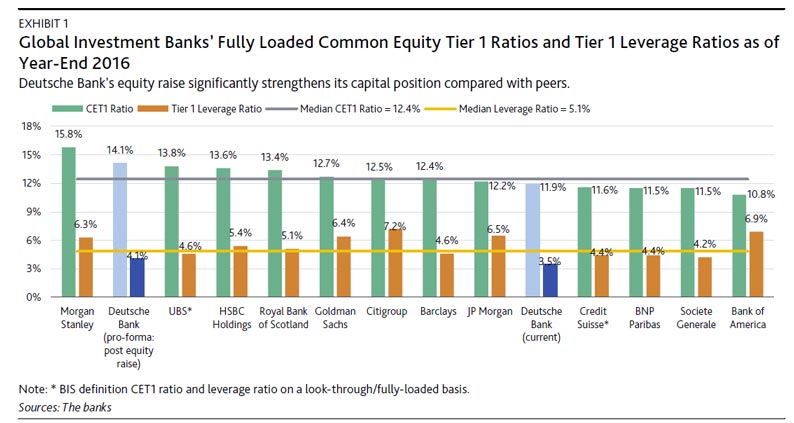

Despite the meaningful restructuring-related charges to date, DB maintained its Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio at 13.4% as of 30 September 2019, a solid buffer above the recently lowered European Central Bank CET1 capital ratio requirement of 11.59%. In addition, DB’s €243 billion liquidity reserve is well in excess of the requirements stipulated by the liquidity coverage ratio, which was 139% as of 30 September 2019 (its net buffer was €59 billion). DB expects its corporate bank unit to report compound revenue growth of 3% during the 2018-22 restructuring period, unchanged from the July announcement. DB aims to build on its strong global transaction banking, cash management and securities service franchises,as well as grow lending to German corporate customers.

DB expects costs to remain virtually flat as it retains client-facing staff and continues to invest in its franchise. Revenue growth will be supported by focusing on the aforementioned focus areas, as well as passing on negative interest rates to partly compensate for challenges in the euro area.

The investment bank unit aims to achieve 2% compound revenue growth, with an increase expected during the 2019-22 period. DB cited stronger-than-anticipated client retention and a rise in top 100 institutional client revenue as supporting its goals over the next few years. The investment bank unit’s profitability should further benefit from the announced cost-cutting measures over time, of which parts will have to be reinvested in technology and infrastructure to maintain leading positions in credit, foreign exchange, fixed income and currencies in Asia-Pacific and Europe, Middle East and Africa. The private bank will suffer most from the even lower interest rate environment. The bank now expects compound revenue growth to be flat over the 2018-22 period, a reduction from the 2% target set out in July. Private banking will remain key to extracting synergies from the integration of the DB franchise with the former Postbank, converting low-margin deposits into fee-producing investment products through collaboration with asset and wealth management, as well as the corporate bank.

The bank expects its asset management unit’s revenue to report a compound annual growth rate of 1% during the period. The reduced target takes into account lower equity market forecasts and a continued strain on margins in the asset management industry. The unit aims to extract a further €150 million of gross cost synergies by 2022, moving its cost-to-income ratio to below 70% (the bank’s asset management unit target is around 65%). Assets under management increased by 9% to €754 billion, driven by positive market performance and another quarter of positive net new money flows. The CRU has been able to downsize exposures faster than anticipated. Quickly reducing the CRU’s revenue and profitability drag to achieve fast and steady progress in reaching the new goals and repositioning DB’s business model will be important to maintaining its current credit strength, as well as safeguarding its capital adequacy metrics.