APRA says their recent changes to securitisation will enable a much larger funding-only market and so provide ADIs the opportunity to strengthen their balance sheet resilience by accessing new sources of term funding, hopefully at relatively attractive pricing. In addition, with the more straight-forward approach to achieving capital relief, securitisation can also be valuable for capital management purposes, perhaps this is particularly so for smaller ADIs and this may bring benefits to the competitive environment. So said Pat Brennan, Executive General Manager APRA, when he spoke at the Australian Securitisation Forum Conference, Sydney and discussed the recent changes to the updated prudential standard APS 120 Securitisation (APS 120), and an associated prudential practice guide.

This marks the culmination of some five years of policy formulation, and APRA’s updates on progress over this period have featured prominently at previous ASF gatherings.

In all prudential policy development APRA is guided by its statutory mandate: to balance the objectives of financial safety and efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality – and in doing so, promote financial system stability. In addition, when finalising the prudential settings for securitisation APRA also remained true to the principles that guided the policy development process throughout:

- to facilitate a much larger, simple and safe, funding-only market;

- to facilitate an efficient capital-relief securitisation market; and

- to have a simpler and safer prudential framework.

Over the last five years APRA’s policy deliberations were greatly assisted by the active engagement of industry in the consultation process. This was both through the ASF and bi-laterally, through formal submissions and informal meetings. It seems fitting at this point to reflect back on this process and note some key aspects of how policy evolved through the consultation process. I will then make a few comments thinking of the role of securitisation looking forward.

Funding only securitisation

Let me start with the subject of the first principle I noted – funding-only securitisation – that is where an Authorised Deposit-taking Institution (ADI) is not seeking capital relief, rather the focus is on accessing term funding to support their lending activities.

Early in the consultation process APRA had serious reservations regarding date-based calls when combined with a bullet maturity structure. Whilst contractually in the form of an option, such a feature may create an expectation that repayment will definitely occur on the stated date regardless of circumstances. This represents a prudential risk should investors be allowed the ‘best of’ either repayment from the underlying pool of loans or from the originating ADI. This type of arrangement is allowed in the case of covered bonds, but controlled within a legislative limit. To allow a proliferation of other covered bond-like arrangements would be imprudent.

Through consultation industry clearly articulated the benefits of bullet maturity structures:

- with their more certain cash-flow structures, a much broader range of investors can be accessed;

- hedging costs for ADIs are reduced, possibly materially so; and

- these factors clearly support a much larger funding-only market.

Industry also accepted that the prudential risk can be managed by the requirements of APS 120, but also through the approach taken by ADIs. Specifically, an ADI should create no impression that the call is anything other than an option for the ADI, and that a call is only exercised when the underlying assets are performing. To put it plainly: an ADI must never bear losses that are attributable to investors.

The finalised APS 120 therefore facilitates bullet structures – this is probably the most significant single development in APRA’s securitisation reforms and is the product of constructive consultation and careful consideration by APRA of how to strike the best balance of the various elements of its mandate.

Tranching

Moving on, many in this room will recall APRA’s early aspiration for a simple, two-class structure with substantially all the credit risk contained in the lower ranking tranche. Such a structure would avoid the problems of complexity and opaqueness associated with securitisation – problems that manifested so clearly through the global financial crisis.

In a general sense simplicity is good – but finance is often not simple. Industry feedback was clear – the concept of a two-class structure has significant shortcomings as the risk preferences of investors in subordinated tranches are varied, and to have an active capital-relief securitisation market greater risk-differentiation, and therefore tranching, is necessary. APRA heard this not only from ADIs but other industry participants as well, including investors – and we were convinced.

As a result APRA has relaxed its approach regarding the number of tranches, though we hope industry will not pursue complexity for complexity’s sake – this is a trap structured finance has fallen into before, with unhappy outcomes.

As a side note, and one that applies much more broadly than securitisation, at times there is a need to consider how things may be, and not be unnecessarily anchored to the current reality we are familiar with. When APRA embarks on this type of consultation it can, on occasion, open possibilities for better outcomes, outcomes that were not previously contemplated, perhaps also bringing opportunities for industry innovation. Policy reform by its very nature is about changing the status quo and industry needs to acknowledge that just because something has traditionally been done a certain way is not, in itself, an argument that it should always be so.

Risk retention

Risk retention is another area where consultation lead to a significant change in APRA’s thinking. Whilst the originate-to-distribute model has not been prevalent in Australia, APRA’s early view was that if there was to be a risk retention requirement it should be set at a level that will truly make a difference and bring alignment of interests between originators and investors. We proposed a level of 20 per cent. At the time there was also an expectation that international practices would be broadly consistent.

As time progressed a variety of skin-in-the-game requirements emerged internationally, generally set at lower levels. Assisted by industry feedback APRA reflected that an Australian requirement, in addition to the varied international requirements, would add regulatory burden for limited prudential benefit. So when balancing APRA’s mandate in the context of the feedback received through consultation, we placed greater weight on efficiency considerations and hence did not implement a risk retention requirement.

Capital requirements

Whilst APRA’s securitisation reforms relate mainly to ADIs as issuers, we are also naturally interested in the amount of capital ADIs hold for their securitisation exposures. We have updated capital requirements following the Basel Committee’s framework, but with adjustments reflecting the Australian context and in light of APRA’s objectives.

Once such adjustment is that APRA has not implemented the approach involving the use of internal models for setting regulatory capital requirements. Instead APRA has implemented the remaining two approaches from the Basel framework: an approach based on external ratings and a standardised approach. Whilst many in industry would have preferred APRA to allow the use of internal models, as we have implemented the risk weight floor of 15 per cent this considerably limits the potential differences in outcomes. This is because a floor of 15 per cent is likely to have been applied to the majority of securitisation exposures if internal models were used, reflecting the relatively high credit quality of the underlying loans. In addition, not implementing the internal models approach is consistent with the objective to have a simpler and safer prudential framework.

A second adjustment is APRA’s requirement that an ADI deducts holdings of subordinated tranches from their own capital. There is frequent comment on APRA’s conservative approach to capital settings throughout the prudential framework. The Basel framework sets minimum standards and the relevant authorities around the globe are expected to set higher standards where they see this as being appropriate – Australia is not alone in setting conservative standards. In the Australian context, with the majority of ADI assets being residential mortgage loans, APRA’s view is there is substantial potential risk in having any incentive in the prudential framework for ADIs to hold the more risky tranches of other originator’s securitisations.

After the lengthy and detailed consultation, APRA is firmly of the view the principles underlying these adjustments are appropriate. I note that, as a result of the consultation process, APRA did relax the level at which the deduction approach applies as industry outlined that with limited additional risk certain common securitisation structures will be viable for ADIs to use if such a relaxation was applied.

Warehouse arrangements

Throughout the process of reforming APRA has been motivated to remove the current unsustainable situation that can arise through warehouse arrangements where capital leaves the banking system with no reduction in risk in the system. In 2014 APRA proposed that a concession remain, but be limited in time to a period of one year. This proposal proved unpopular with industry, which APRA found a little surprising at the time given it was designed to retain the concession in full for a year, and we anticipated this would be economically attractive over at least a two year period. Nevertheless, industry feedback was clear and negative.

In 2015 we put this subject back to industry to propose potential solutions, noting that in the absence of any viable option being identified APRA would simply treat warehouses as any other securitisation – either capital relief or funding only depending on the degree to which each arrangement meets the relevant requirements.

The feedback we received generally asked for the existing concession to remain indefinitely, and as APRA had said, that was unsustainable. So on warehouses, the consultation process did not offer any viable alternatives.

The final APS 120 accommodates warehouses, but with no special treatment when compared to other forms of securitisation. APRA hopes that efficient funding structures are agreed between market participants so the benefits of warehouse arrangements can continue.

From these examples you can see that the final form of APS 120 is different to how it would have appeared if it was finalised even just two years ago, and very different to how it would have appeared if it was finalised a year or two prior to that. APRA has materially changed some policy positions and modified others as a direct result of consultation. In a few areas, where the prudential stakes were sufficiently high, APRA did not change its basic position – though the consultation process brought healthy challenge to APRA’s approach and caused us to consider aspects of the policy from a new perspective. In both cases – where policy was changed and where it was not – a constructive consultation process proved essential to arrive at the best possible prudential policy.

Looking forward we all hope to see the Australian securitisation market grow and prosper. Having a much larger funding-only market would provide ADIs the opportunity to strengthen their balance sheet resilience by accessing new sources of term funding, hopefully at relatively attractive pricing. With the more straight-forward approach to achieving capital relief, securitisation can also be valuable for capital management purposes, perhaps this is particularly so for smaller ADIs and this may bring benefits to the competitive environment.

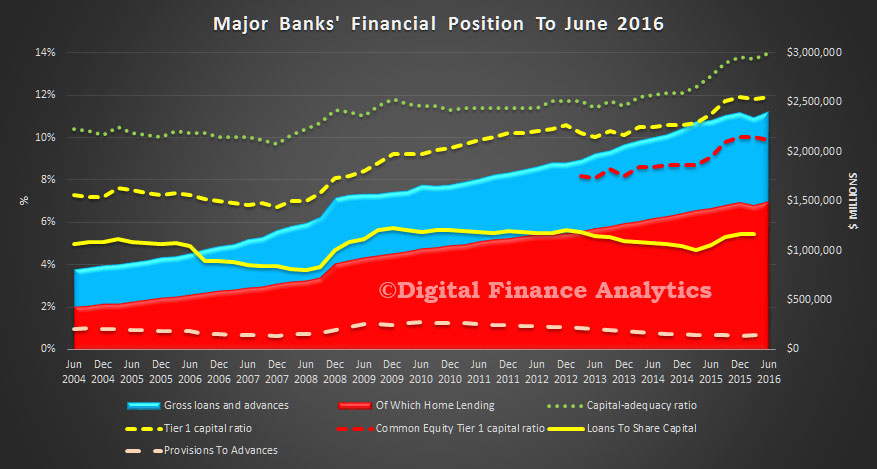

APRA is soon to finalise the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) to be applied to 15 larger, more complex ADIs, and this is expected to be implemented in 2018 alongside the securitisation reforms. The Australian banking system has some notable features that are not very common around the globe. On the asset side the banking system essentially funds lending for housing on its collective balance sheet, whilst on the liability side the Australian banking system has a relatively low deposit to loan ratio. Whilst the affected ADIs are reasonably well placed to meet the NSFR requirement, new opportunities to strengthen funding profiles will assist in strengthening this measure over time – and this strengthening will make the system more resilient.

Whilst a much larger Australian securitisation market depends on market forces, which have ebbed and flowed considerably in recent years, it seems certain that over time opportunities to grow the market will present themselves. The updated prudential framework, and accommodating bullet maturity structures in particular, places ADIs well to take advantage of those opportunities as they arise.