These uses are merely the tip of the proverbial iceberg for a nascent technology whose development stage has been compared to the early years of the internet. “We’re very early in the game,” said Brad Bailey, research director of capital markets at Celent, at a recent Blockchain Opportunity Summit in New York. He likened the blockchain’s current status to the web of the early 1990s, heralding a coming wave of new ideas and uses. “This will impact the world.”

The blockchain technology came about initially as a way to verify bitcoin transactions online and to enable two parties to transact business without having to know or trust each other. It was designed without a central authority in mind, such as a bank or government, to oversee transactions. Essentially, the blockchain is a shared virtual public ledger where encrypted transactions are confirmed by outside parties. In the bitcoin world, these outside parties are called “miners” — computers that solve complex mathematical problems to confirm transactions and earn fees. Confirmed transactions are placed in a “block” and added to the chain. Since the ledger is shared by everyone on the network, it is thought to be nearly impossible to remove or change the data – a premise that turned out to be false in some cases.

Today, the concept of the blockchain has expanded beyond its use by cryptocurrencies. Instead, the benefits of the shared ledger and its seemingly immutable record of transactions accessible to multiple parties are being explored by a variety of industries. Experts said there won’t be a “mother blockchain,” but multiple ledgers with different purposes. Varying versions of blockchains have popped up, too: While the original bitcoin blockchain was open to anyone, some companies’ blockchains are private and “permissioned” — they restrict access to approved parties. The latter approach is preferred by companies fearful of being hit with government fines and lawsuits if they get hacked, said summit participant Sarab Sokhey, chief technology leader of new product innovations at Verizon Wireless. They’ll stay private until the technology matures and industry standards are set.

While the blockchain’s business applications are clear, it has social implications as well. For instance, it can create identities for individuals apart from those sanctioned by governments and not limited by geographic boundaries. The blockchain also allows less-technologically advanced nations to participate in global transactions more easily. “Blockchains are exciting, undoubtedly,” said Saikat Chaudhuri, executive director of the Mack Institute for Innovation Management, which was an official partner for the summit. “It’s much more than about transaction efficiency or flexibility. It’s really beyond that. It could provide an identity to those who don’t have it, or promote financial inclusion. Therein lies the power of this whole thing.”

‘Nervous’ Financial Institutions

According to a survey by the IBM Institute for Business Value and the Economist Intelligence Unit, one in seven companies it calls “trailblazers” expect to have blockchains in production and at commercial scale in 2017. Respondents were interested in taking advantage of the blockchain’s multiple benefits, which include cost reduction, immutability of records, transparency of transactions and the potential to create new business models. For example, the blockchain would eliminate the need for keeping multiple records at banks and other parties doing currency trades. The survey tracked responses of 200 global financial markets institutions.

The survey also said “trailblazers” were focusing their efforts on the following business areas: clearing and settlements, wholesale payments, equity and debt issuance and reference data. The report added that in recent years, financial institutions have “swarmed to blockchain pilots and proofs of concept” — opening innovation labs, holding hackathons, partnering with financial technology startups, joining consortia and collaborating with regulators.

To be sure, banks have a vested interest in participating. “Banks provide essentially escrow services for the transfer of value, and here comes a technology that threatens to eliminate that service,” said Chris Ballinger, global chief officer of strategic innovation at Toyota Financial Services. “So they are nervous about that, because it’s a huge revenue stream” that could be taken away. How? “With the blockchain, you can run a network that transfers value among untrusted nodes, and therefore you can eliminate the middle man and you can eliminate all the costs associated with the middle man,” he said. “You’re essentially turning assets into something like cash that you can hand to somebody and they will accept. That makes the transfer of assets extremely efficient.”

Another unique benefit of the blockchain is that it separates someone’s identity from the transaction they’re making. In general, a blockchain uses a digital signature – not real names and other personal information – that is activated by a private key or secret code held by the one doing the transaction. Compare that to current credit card or bank transactions, which tie one’s personal information such as a name and address to purchases and other financial activities. This separation improves the security of one’s data. “Today, the payments information and identity are [bound] together. The combined is a tempting honey pot for hackers,” Ballinger said. “By separating the financial information from the identity, there’s no honey pot, no central place to hack, no incentive to go after.”

In December 2015, Nasdaq executed its first trade on a blockchain, through its Linq ledger. The exchange said the blockchain promises to expedite trade clearing and settlement – all the steps needed to transfer the asset from seller to buyer including recording the transaction — from three days to as little as 10 minutes. That’s because the trades remove many manual processes and bypass third parties. As such, “settlement risk exposure can be reduced by over 99%, dramatically lowering capital costs and systemic risk,” according to Nasdaq. Other stock exchanges tinkering with the blockchain include ones in Australia, Myanmar, Germany, Japan, Korea, London and Toronto.

Overstock.com is on the cusp of issuing its first security using the blockchain. “We are in the process of proving out the first public trading of a blockchain security,” said Ralph Daiuto, Jr., general counsel of tØ, a subsidiary of the e-commerce retailer. While the company has kept its clearing firm, it is using digital wallets for the actual transfer of assets in settlement of the trade. “The goal is to shorten the settlement cycle and [avoid] all the ills that can go wrong with that cycle.” He added that the company can cut its equity trading costs by 70% using the blockchain.

Overstock got regulatory approval for its blockchain trade by taking “incremental steps in proving out the technology in use cases and demonstrating we have real-world application for this blockchain technology,” Daiuto said. “It literally has been a monthly, if not a weekly, education process with our core regulators.” It has taken nearly two years of laying the groundwork for Overstock to get to this point.

Real Estate and Smart Contracts

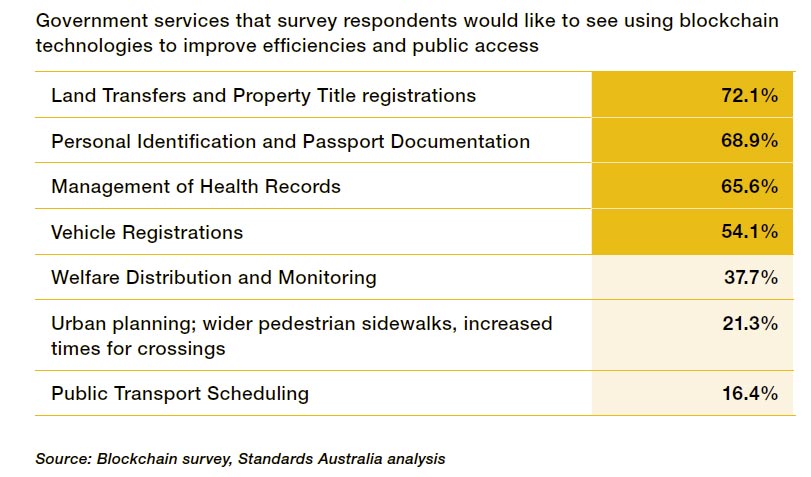

An area of particular promise for the blockchain is the real estate market. “The blockchain solves pretty much every problem in real estate that we have” in terms of fraud, middleman fees and friction, opaque due diligence, slow price discovery, complex transaction process and other ills, said Ragnar Lifthrasir, president of the International Blockchain Real Estate Association. “In many ways, our technology is still in the 17th century – notaries still use seals.” The blockchain promises to simplify and speed up the process while adding transparency to the records.

For example, in selling a house, people still sign paper deeds over to the new owner. It has to be entered into the public record, which means someone physically has to go to the local government office. “It’s a paper-based system that is ripe for fraud,” Lifthrasir said. The blockchain solution is fairly straightforward, using digital deeds. “When I want to transfer the property, I simply transfer it from my wallet to the buyer’s wallet.”

As for putting the property ownership on the public record, he said the list is already on the blockchain so recording it won’t be hard. Lifthrasir added that validation of ownership would be strengthened. “It’s very difficult to deny who owns the property when it’s on a public network.” His startup, Velox, is working with Cook County in Chicago to use the blockchain for transferring and recording property titles. It is also working on a way to show liens on titles on the blockchain.

Within a blockchain, so-called “smart” contracts could be revolutionary. “They programmatically represent a contract,” said Mark Smith, CEO of Symbiont and co-chair of the Smart Contract Council. For example, a smart contract on an auto loan could be linked in real time to payments made by the car buyer. If he misses payments, the contract gets wind of the violation and starts the repossession process. In Delaware, Smith’s company is working with the state to create “smart” records of its public archives to do such things as being able to sunset themselves.

EY’s Australian operations piloted a real estate blockchain ecosystem that is now being used in the market to trade full, and even fractional, ownership of properties. Real estate and financial institutions approved by EY all liked the idea of using a blockchain, but when it came to actual implementation, “fear and uncertainty crept in,” said James Roberts, partner and Australian blockchain leader. EY had to essentially guarantee verification of participants and transactions to build trust. “We decided we would solve the identity problem [of people and institutions]. We would build trust into the system and prove recordkeeping is true and accurate and can be used to transact financial instruments like property or debt.”

EY’s blockchain ecosystem goes through several stages. First, individuals using the blockchain have to be validated using identity checks and even biometrics. They create records on the blockchain using randomly generated unique keys that let EY do further checking against various databases from the government and elsewhere. Next, the transaction is traded on a blockchain exchange. The assets being traded are verified. The entire ecosystem is private and permissioned. Also, EY stores individuals’ unique keys offline for security. Moreover, EY built back-system administrative functions – despite the premise of the blockchain as not having a central authority – to make participants more comfortable in using the system. But to be a viable ecosystem, it needs to scale. “We need millions and millions of people in our system, and that’s going to take a lot of effort,” Roberts said.

Challenges and Risks

Security is still the biggest challenge confronting the blockchain. “The truth is, once you give someone access to a network, many times, more often than not, they can end up very easily getting blanket access to that network,” said Joe Ventura, CEO of AlphaPoint. “This is a huge security problem.” However, if one ends up building many protections to prevent hacks, then it bogs down the blockchain and defeats its purpose in the first place. “Basically, you have to jump through so many hoops simply to pass the message from some party to another party.”

And while blockchain records theoretically can’t be changed, there are ways around that. Smith cited a recent controversial decision by the Ethereum Foundation – the organization behind the open-source cryptocurrency Ethereum – after a hacker exploited a software flaw and took funds. The foundation decided to roll back the clock to give people their money back and created two versions of the ledger. “Imagine if you’re a business and they roll back a day,” Ventura said. “That’s completely unacceptable.” Moreover, by creating two versions, some people were able to exploit it. “People were able to double their money,” Smith said.

As for compliance, at least regulators could have a node on the blockchain itself in which companies define their access to data, said Sandeep Kumar, managing director of Synechron. As such, regulators wouldn’t have to wait days for a bank to hand over documents for compliance. “They can see it as it is happening.”

In the end, each company has to figure out whether a blockchain is suitable. “Is it a blockchain use case or is it a database use case?” said Tyler Mulvihill, director of Consensys. “If you are a company that has a lot of information internally and you don’t transact like a lot of vendors, and not a lot of people need to use your information or do business with you, a database can be fine for a lot of things. It’s when you have a lot of parties that need trust, need access to certain information and need to be audited – that’s where I see the biggest use cases.”