Mr Borio, the world is facing many problems. What is the root cause?

We do not know for sure. The big questions in economics have not quite been solved. But let me start by saying that the rhetoric about the global economy is worse than the reality. In terms of global growth, we are not that far away from historical averages, especially if we adjust for demographics. Moreover, unemployment has been declining, and in several cases is close to historical norms or measures of full employment.

So everything is fine?

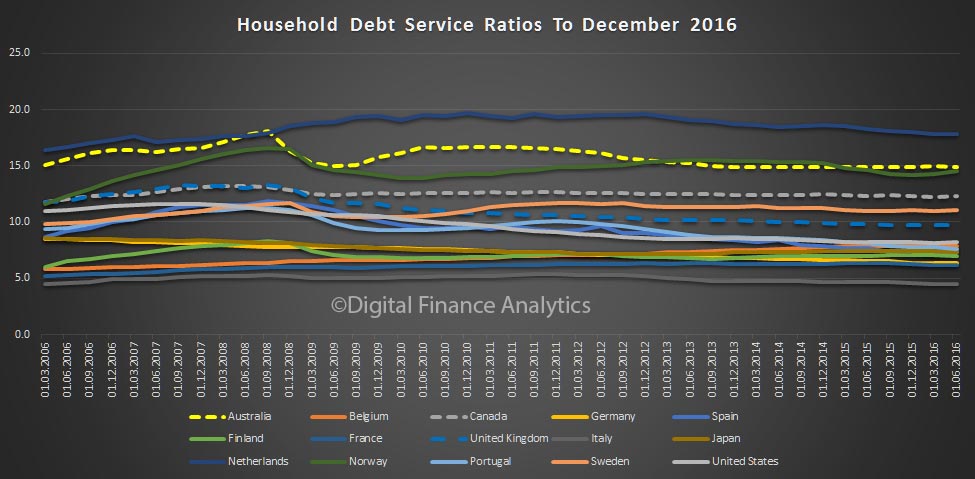

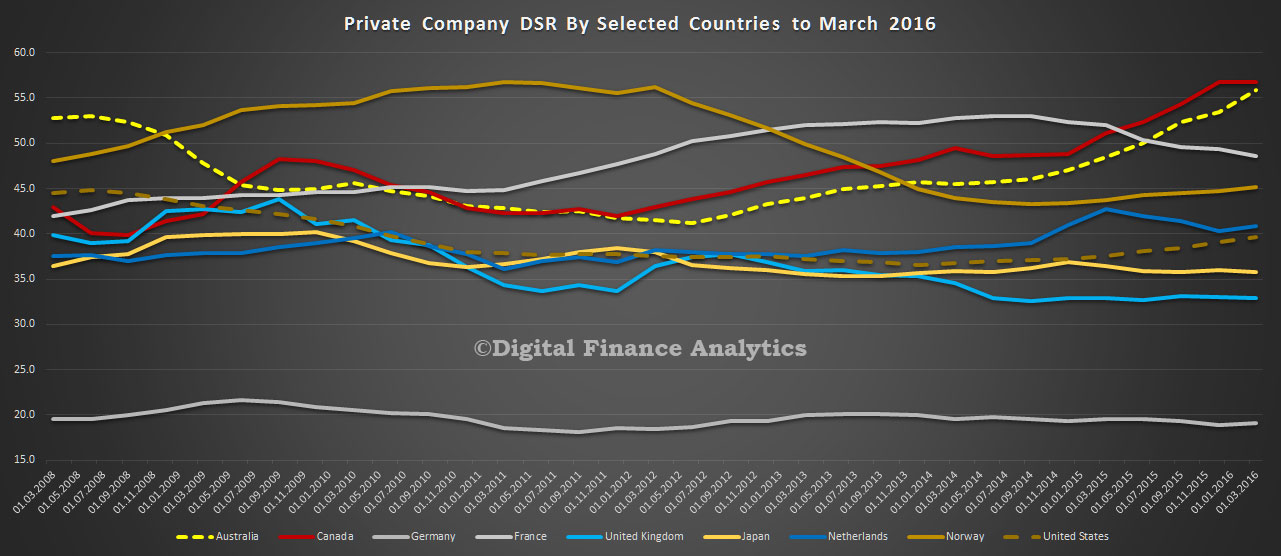

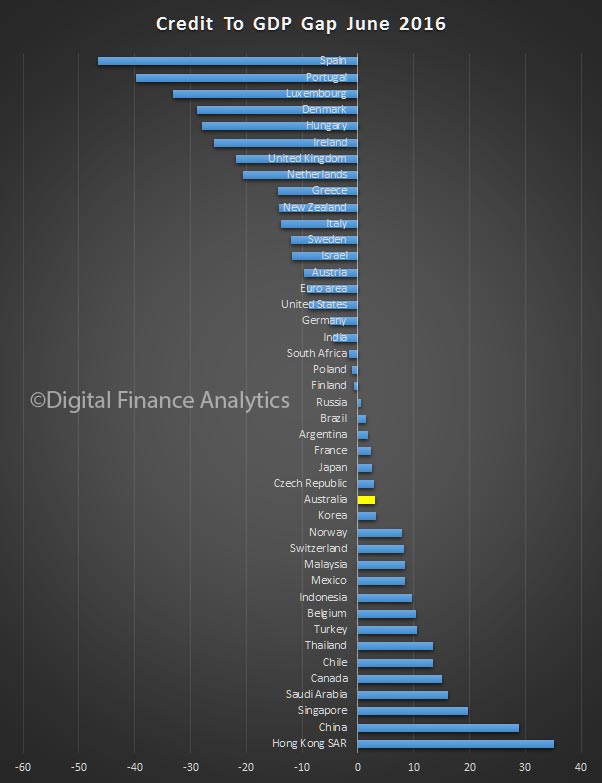

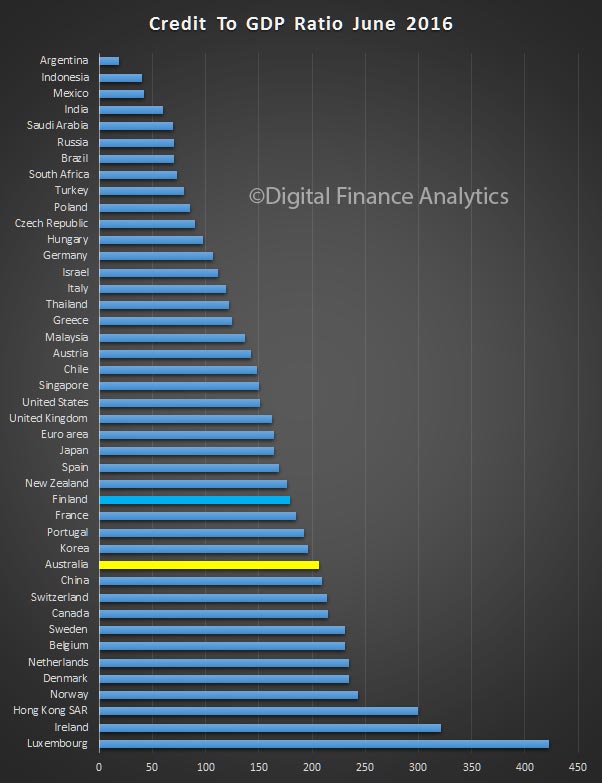

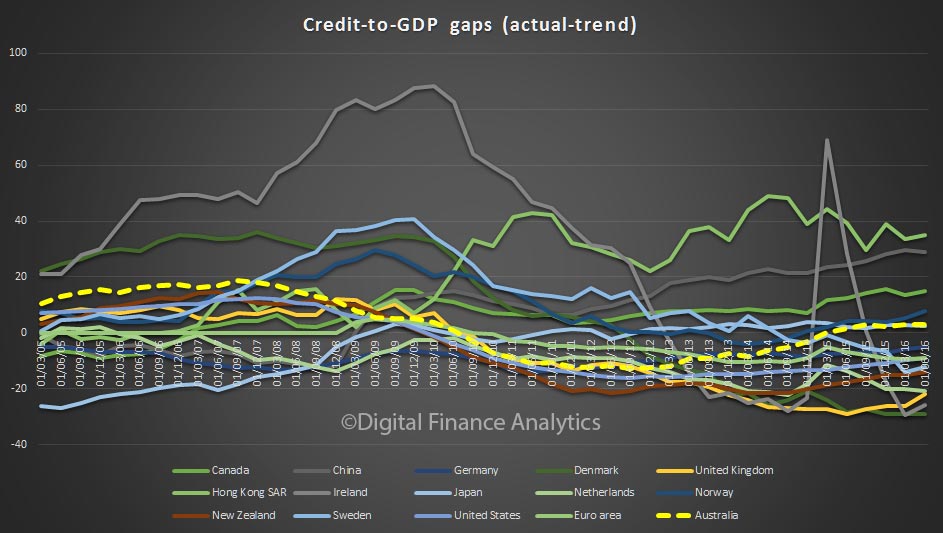

It is the medium term that is our concern – what we have called the “risky trilogy”. The long-term decline in productivity growth has accelerated since the crisis, so that the prospects for long-term growth are not bright. Debt levels, both private and public, are historically high and have been increasing since the crisis. And, most critically, the room for policy manoeuvre, both monetary and fiscal, is limited.

But can central banks help out?

Monetary policy has been stretched to its limits. In inflation-adjusted terms, interest rates have never been negative for so long and they are lower now than in the midst of the financial crisis, which is odd since the situation has improved. If you came from Mars and they told you that policymakers were struggling to reach price stability, you might be surprised, as inflation is not far from measures of stable prices. But since many central banks have inflation targets set at 2%, there is a lot at stake.

Why do we have low inflation?

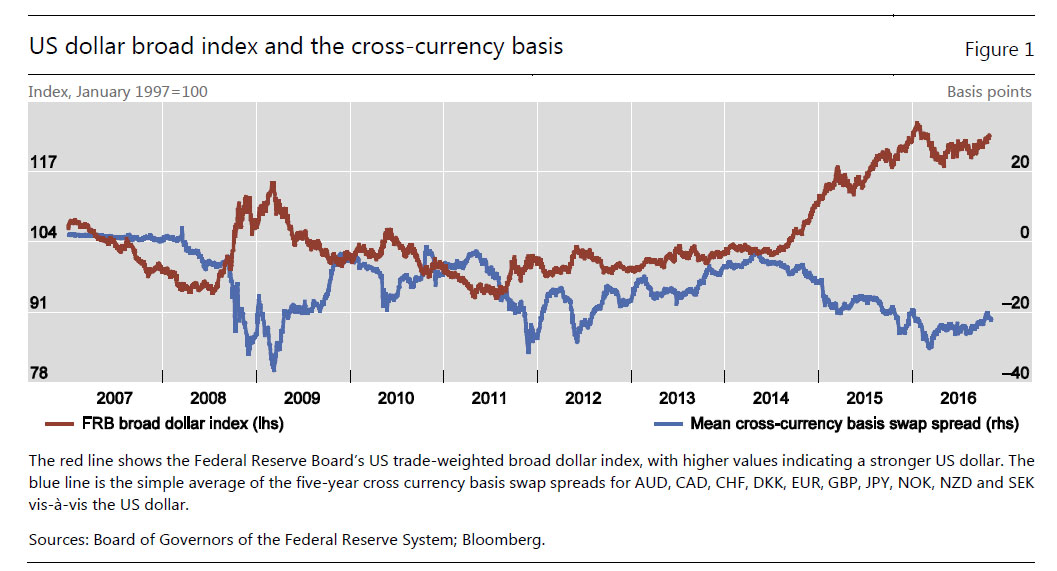

We do not fully understand this. But I think we have underestimated the long-lasting impact of the globalisation of the real economy, notably the entry of China and former communist states into the world trading system. There has been persistent downward pressure on wages and prices, as competition has greatly increased, helped also by technological change. The pricing power of producers and, in particular, the bargaining power of workers have declined, making the wage-price spirals of the past less likely.

The ECB and other central banks fear deflation.

Building on previous work, we have analysed deflation across many countries since the 1870s. There is only a very weak link between deflation and slow growth. That finding has not received the attention it deserves.

What should central banks be doing?

The idea is to look carefully at what is driving disinflation and use all the flexibility available in the mandate to reach the 2% inflation target. To form a judgment is not easy, but is always necessary. Whether deflation is costly or not depends on its drivers. For instance, to the extent that it is globalisation, it is not costly, as it is supply-driven rather than the reflection of weak demand.

Where is the danger?

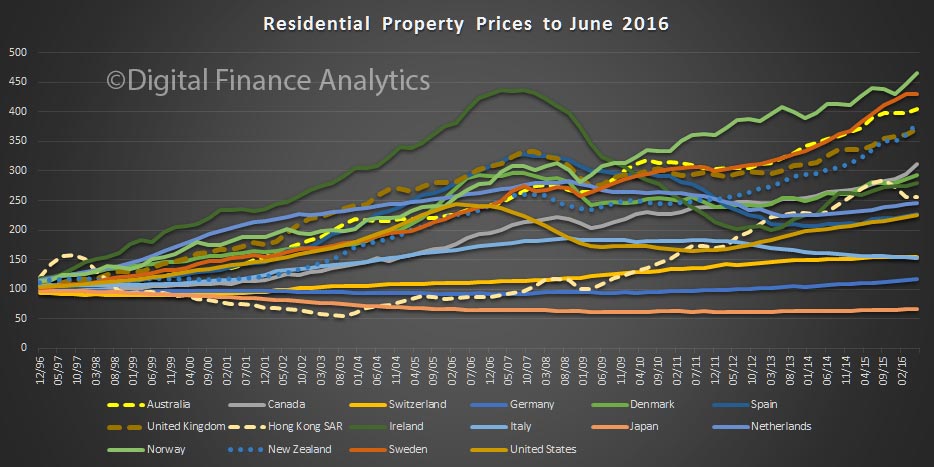

Around 2003, policymakers were also concerned with deflation, and as a result kept interest rates very low. But this contributed to a credit and property price boom that sowed the seeds of the bust that did so much damage later on. In the crisis years after 2008, it was essential to loosen monetary policy. But since then, monetary policy has been overburdened. On balance, too little has been done to repair balance sheets and to raise sustainable growth through structural reforms, such as by making markets more flexible and promoting entrepreneurship and innovation.

And more fiscal spending?

Only where there is room. Public debt in relation to GDP has never been so high in so many countries during peacetime. Fiscal space should not be overestimated. It is all too easy to end up with an even larger pile of debt.

The global debt is around $90 trillion, and it is rising. How should one reduce it?

How to manage the debt burden is the hardest question. The best way, of course, is to grow out of it, which is why structural reforms are so important. Other forms are more painful.

Do you fear political populism?

I fear a return to trade and financial protectionism. We are seeing some worrying signs. The open global economy order has been remarkably resilient to the financial crisis; but it might not so easily survive another one. At that point, we could see a historic rupture. That is an endgame we should do all we can to avoid.

There are academics and politicians advocating the abolition of cash. What do you think of that?

Negative nominal interest rates, especially if persistent, are already problematic. Quite apart from the problems they generate for the financial system, they can be perceived as a desperate measure, paradoxically undermining confidence. Getting rid of cash would take all this one big step further, as it would signal that there is no limit to how far into negative territory nominal interest rates could be pushed. That would risk undermining the very essence of our monetary economy. It would be playing with fire. Also, it would be quite a challenge for communication, even in simply economic terms. It would be like saying: “We want to abolish cash in order to tax you with lower negative rates in order to – tax you even more in the future.”

Why?

Because the reason for doing this would be to raise inflation – which is perceived as an unjust tax on savings. This would require people to have faith in the “model” which policymakers use to steer the economy. Quite a challenge!

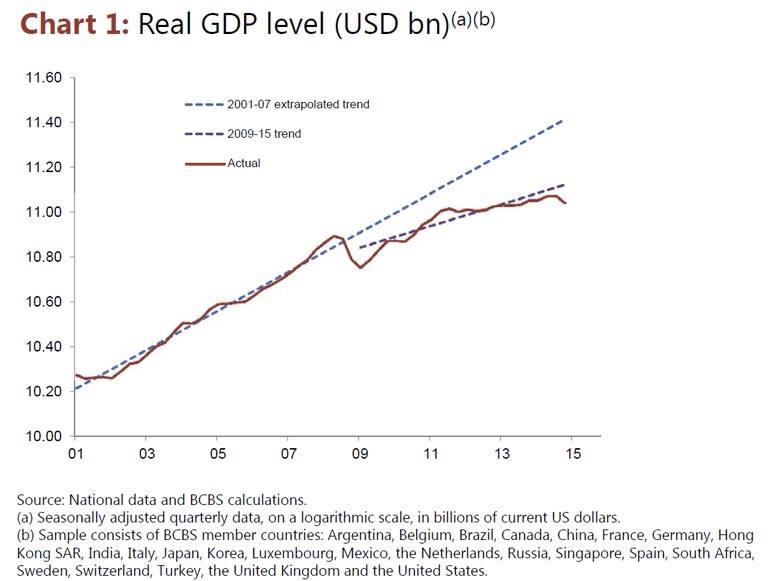

Bank failures, government bail-outs and subsequent monetary policy settings have combined to lower overall real GDP.

Bank failures, government bail-outs and subsequent monetary policy settings have combined to lower overall real GDP.

The BIS says

The BIS says