“schmozzle (plural schmozzles). (informal) A disorganized mess; (informal) A melee”.

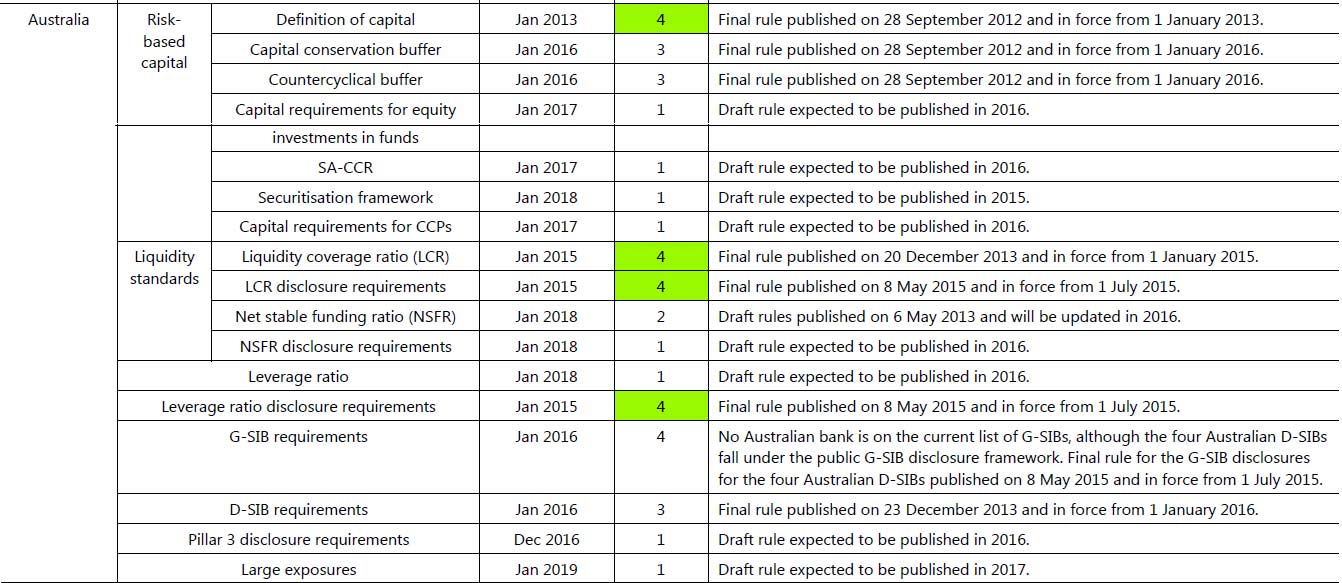

When the FSI inquiry was handed down last year, with recommendations mostly later accepted by Government, a cornerstone was to avoid the risk of a failing bank needing to be bailed out by tax payers, as happened in a number of countries during the GFC.

A year later, we can look back to see significant changes to the current capital rules for “Advanced” banks (those that use their own approved internal models) and significant capital raisings of more than $30bn by the industry. This has translated into higher interest rates on mortgages, especially investment property loans.

Currently underway are discussions about the next iteration of the capital rules, with the expectations that “Advanced” banks’ rules will be tightened, and the rules for other banks will get more complex, with capital ratios being determined for example by the loan-to-value (LVR) of loans, as well as differentiation between loans serviced by income, and those materially serviced by rental income flows.

APRA last week said they would look to encourage more banks to move towards the “Advanced” methods, with a series of potential interim steps, at the time when the rules are under review. They also said that the current counter cyclical buffer would be set to zero.

Five Australian Banks have “Advanced” capital management, and a number of other banks are already on the journey to “Advanced” capital methods; but it is a complex and twisted path, and the destination is not yet clear. Better data, models and systems are required to meet the necessary hurdles.

What is likely though is that the journey to hold more capital is far from over, whether “Advanced” or “Standard”, and that the light between the two systems is closing, as the “Standard” system gets more complex, and the “Advanced” ratios are lifted higher.

We think that there will be only limited upside to be gained from moving to “Advanced”, as the gap closes, and complexity increases in the standard approach. We also think significant further capital will be required – some are suggesting an additional $30-40bn in the next couple of years, enough to force mortgage prices across the board significantly higher again. As these adjustments are essentially across the board, to a greater or lesser extent, we doubt that smaller players will actually get much differential benefit. Indeed, if investment mortgages require higher capital still. (that depends on the definition of what is “material” – yet to be made clear; and the LVR), some banks could need much more capital than is currently assumed.

It is also worth noting that spreads on overseas bank capital raisings are rising, indeed, spreads are wider now across the market, as we noted last week.

So what is the potential impact of lifting capital ratios? We already mentioned the uplift in mortgage rates, as banks seek to cover the additional costs involved. Households should expect to pay more. Shareholders may also have to take a haircut in future returns, as the economics of banks change. The super profits banks have enjoyed may be trimmed a little.

But a recent paper from the Bank of England has also highlighted that lifting capital may not reduce systemic risks much. The study, a working paper “Capital requirements, risk shifting and the mortgage market” looked at what happened when capital ratios were lifted. They found that whilst the average value of a loan made fell a little, there was no reduction in higher risk lending, despite the requirements for higher capital, because the lender was looking to protect overall margins and still chose to take more risks. If this is true, higher capital requirements does not necessarily reduced systemic risks. Banks may still need Government support in a crisis.

But wait, was that not the whole reason for lifting capital ratios in the first place? Looks like a schmozzle to me!