ANZ’s address makes three points. The levy should be temporary, should be applied to foreign banks, and the costs will be passed on in one way or another.

Good morning and thank you for the opportunity to appear today.

With me today are Rick Moscati, our Group Treasurer, and Jim Nemeth, our Head of Tax. While ANZ is disappointed by the bank levy, we accept that it will become law.

Our aim today is to work constructively to ensure that the legislation is as fair and efficient as possible.

We appreciate the changes made already to the treatment of derivatives and that the rate of the levy is reflected in the Act.

I have three points to make briefly today in relation to our submission.

Firstly, as one of the principal reasons for the levy is budget repair, we think that the levy should cease when the budget returns to surplus.

Secondly, we believe the levy should apply to major foreign banks operating in Australia and exclude the offshore branches of Australian banks. This would be consistent with principles of international taxation, avoid double taxing Australian banks and mean that all major banks in Australia, foreign or domestic, are treated equally. Without the levy applying to major foreign banks, Australian banks will be at a significant disadvantage in the institutional markets where foreign banks mainly compete.

Further, we borrow money in offshore branches to lend to offshore institutional customers. If the levy applies to our foreign branches, it makes us less competitive overseas. This will constrain Australian banks’ ability to develop offshore business and serve customers in the region.

Recent amendments to the UK levy are consistent with this. That levy applies to large foreign banks operating in the UK and is being amended to exclude UK banks’ offshore liabilities.The reasons for this approach include ensuring UK banks are not hurt by operating offshore and to tax foreign and domestic banks equally. The same rationale applies to Australia.

My last point is that we are concerned about the combined impacts of increased bank regulation and the levy.

We believe there should be appropriate reviews of how these policies interact.

Speaking to international investors recently, they share these concerns, not just in relation to the banking sector, but also in relation to broader investment in Australia.

The points I’ve made concerning a levy sunset and reviewing its cumulative impact with other policies would help alleviate these concerns.

Before I close and to anticipate your questions, we have not decided how we will respond to the levy. In any event, there are legal limitations to what I can say today.

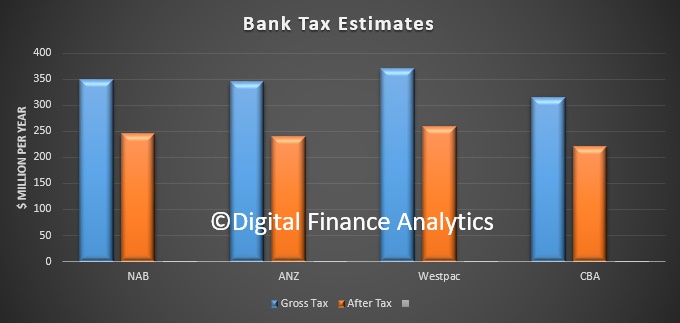

However, we cannot ‘absorb’ the levy. Based on ANZ’s 31 March Balance Sheet, we estimate that the annualized financial impact of the levy would have been $345 million before tax.

It is an additional cost that the shareholders, customers and employees of ANZ will bear.

Our options are to reduce what our owners receive, reduce our costs or charge higher prices.

As announced last year, ANZ has already reduced what our owners receive by cutting our dividend. We are also already focusing heavily on reducing absolute cost levels. We have reduced costs over the last year and announced that we are working on further reductions.

ANZ will continue to work constructively with you and your Parliamentary colleagues to ensure that the levy is as fair and efficient as possible.