Please consider supporting our work via Patreon

Please share this post to help to spread the word about the state of things….

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

We look at the latest Ratings Agency Ratings.

Please consider supporting our work via Patreon

Please share this post to help to spread the word about the state of things….

New data suggests that our four major banks are less well capitalised than you might expect, so today we discuss the implications.

Back in 2014, ex-Commonwealth Bank of Australia chief David Murray lead a financial system inquiry which recommended that Australia’s banks should maintain “unquestionably strong” status from a capital perspective. Specifically, to avoid issues in a crisis, the review recommended that they should be in the “top quartile” of banks globally relative to their international peers in terms of capital strength. All but one of his recommendations were accepted by the Government.

Back in 2014, ex-Commonwealth Bank of Australia chief David Murray lead a financial system inquiry which recommended that Australia’s banks should maintain “unquestionably strong” status from a capital perspective. Specifically, to avoid issues in a crisis, the review recommended that they should be in the “top quartile” of banks globally relative to their international peers in terms of capital strength. All but one of his recommendations were accepted by the Government.

Murray told The Australian Financial Review on Tuesday the “unquestionably strong” target was introduced to deal with two issues. The first was to ensure that if the government did have to support the banks in a crisis they would eventually get their money back. The second issue was to allow the banks to retain the faith of foreign investors in a systemic downturn, given the reliance on international debt capital markets.

APRA, the prudential regulator was then given the task of defining the “unquestionably strong” target that sharemarket investors at the time feared would force the banks to conduct dilutive capital raisings.

The banks have indeed increased their capital since 2014, but it was only in July 2017 that APRA provided clear guidance, setting a common equity tier one ratio target of 10.5 per cent. The banks were given 2½ years to achieve the modest uplift, and at the time bank stocks rallied on the limited targets and extended timeframes. APRA said the 10.5 per cent target also factored in expectations that global banks would increase their capital levels. Their subsequent papers did not change this fundamental target, even if the mix may change.

But despite being depicted by the government and the media as among the most secure in the world, the big four banks are no longer “unquestionably strong,” according to an S&P Global Ratings report released recently. The reason is their exposure to record levels of household debt and declining real estate values.

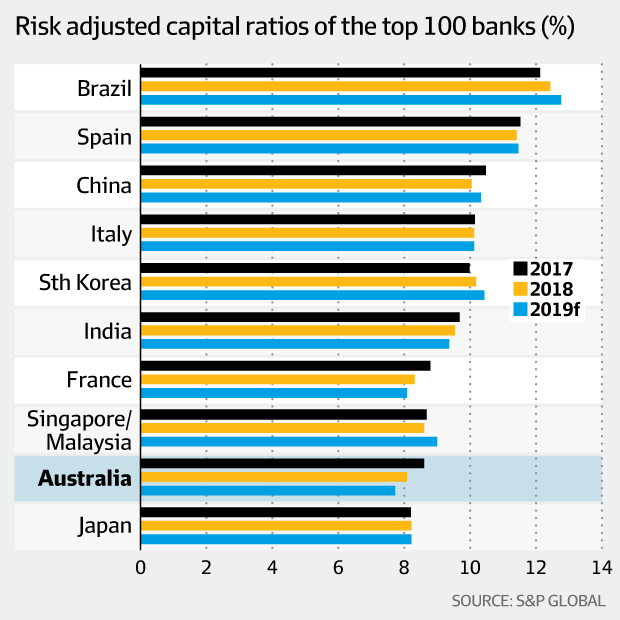

Based on a survey of 100 world banks compiled by S&P Global Ratings, Australian banks last year experienced among the “steepest declines” in their risk adjusted capital, or RAC, pushing them into the bottom half of global rankings. They would need to raise billions of dollars to return to the “unquestionably strong” top quarter of lenders.

This is because banks in other major economies bolstered their capital positions, while the economic risks posed by high levels of household debt and inflated property prices prompted S&P to penalise the Australian banks.

This is because banks in other major economies bolstered their capital positions, while the economic risks posed by high levels of household debt and inflated property prices prompted S&P to penalise the Australian banks.

This result, reported on the front page of the Australian Financial Review last Wednesday, but virtually nowhere else, is another indicator of a potential property and financial crash that would have devastating economic consequences, for the economy and households.

The capital decline has placed the four major banks around the 40th to 50th percentile of surveyed banks when ranked by the RAC ratio, the credit rating agency’s preferred measure of financial strength.

That is well outside the much trumpeted “top quartile” target set by regulators as a result of the David Murray-led 2014 Financial System Inquiry.

The AFR says that the S&P RAC ratio is calculated by dividing a bank’s total capital by its risk-weighted assets. The risk-weighted assets figure is adjusted by the agency based on the prevailing economic risk score of the country in which the bank operates.

The RAC scores of the big four banks range between 8.9 per cent (National Australia Bank) and 9.4 per cent (Commonwealth Bank).

That is below the average 10 per cent ratio that APRA said would “would improve the likelihood of being perceived by financial market participants as having unquestionably strong capital ratios”.

The RAC ratios do, however, factor in the agency’s dimmer view on the economic risks in Australia that had resulted from a build-up in household debt.

S&P’s decision in May 2017 to downgrade the economic risk score in Australia sliced about 90 basis points off the RAC ratios of the Australian banks, APRA said.

The prudential regulator said it preferred to calculate the RAC using a higher “normalised” economic risk score, which put the banks in the 10 per cent range.

But the S&P commentary is yet another signal of potential trouble ahead.

In this discussion Economist John Adams and I explore the whole question of “Bank Bail-In”, with specific reference to bank deposits.

Please consider supporting our work via Patreon

Please share this post to help to spread the word about the state of things….

John has written an article on this

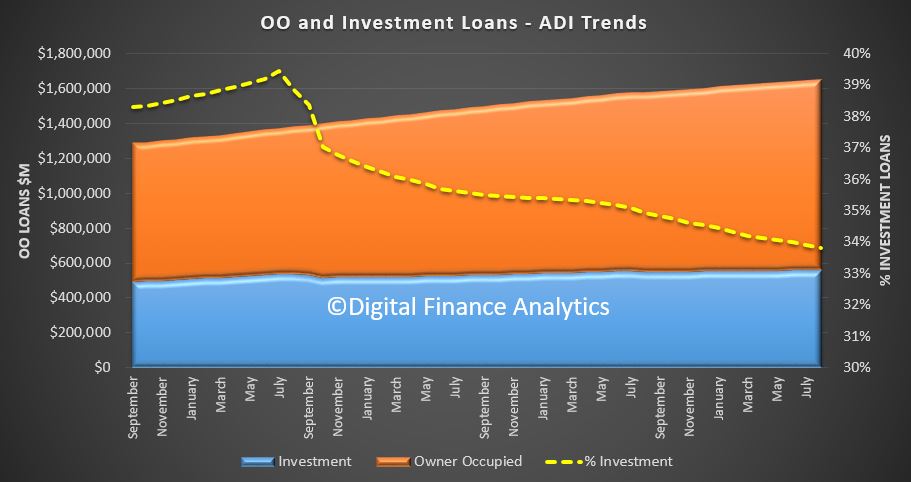

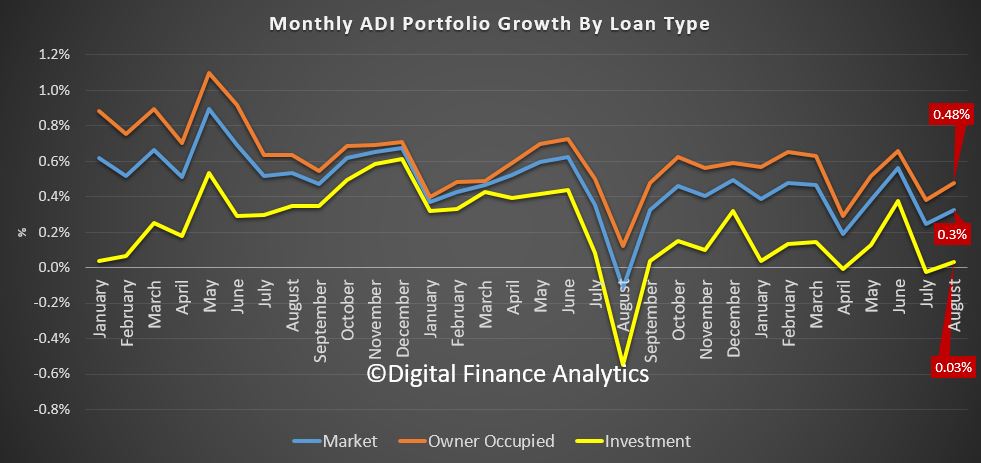

APRA has released their latest banking stats to end August 2018. Total lending for residential homes rose by 0.33% in the month to a total of $1.65 trillion. Another record. That would be an annual rate of 3.9% if repeated each month, a little lower, but still nearly twice wages growth, so household debt is STILL climbing.

Within that lending for owner occupation rose 0.48% to $1.09 trillion and lending for investment purposes rose 0.03% to $557.6 billion (last month it dropped by 0.02%). 33.8% of loans are for investment purposes.

Within that lending for owner occupation rose 0.48% to $1.09 trillion and lending for investment purposes rose 0.03% to $557.6 billion (last month it dropped by 0.02%). 33.8% of loans are for investment purposes.

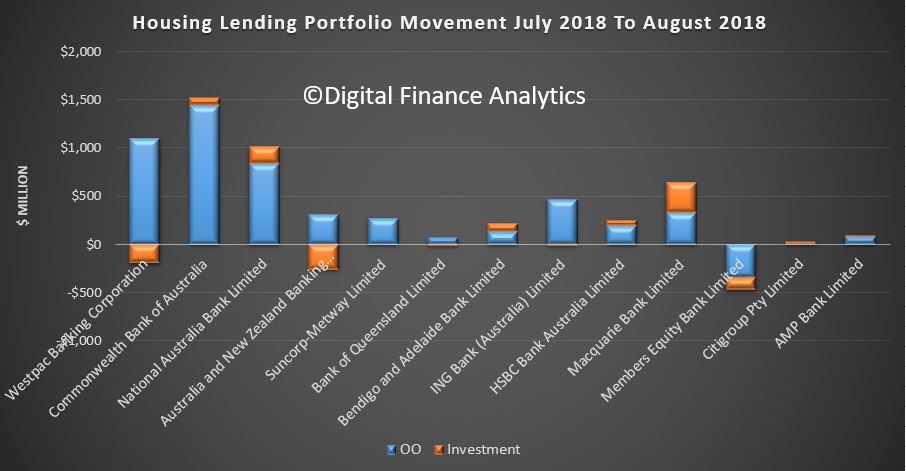

Looking at the portfolio movements, NAB, CBA, Bendigo, HSBC and Macquarie reported a lift in investor loan balances. Westpac and ANZ reported a fall. ME Bank appears to be losing relative share on both fronts.

Looking at the portfolio movements, NAB, CBA, Bendigo, HSBC and Macquarie reported a lift in investor loan balances. Westpac and ANZ reported a fall. ME Bank appears to be losing relative share on both fronts.

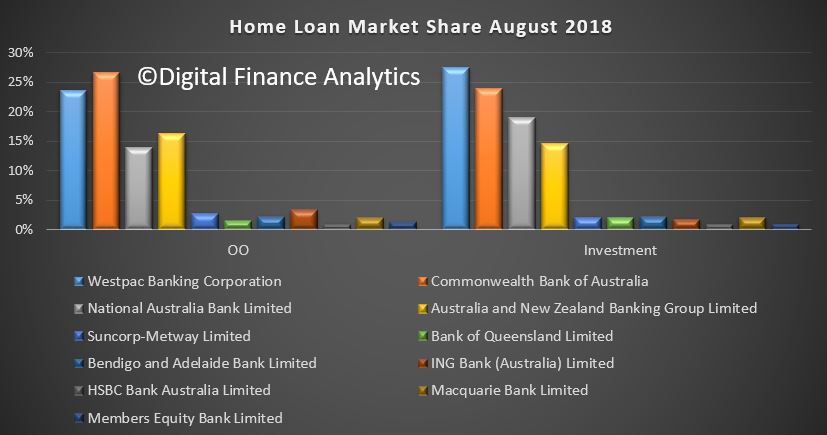

The market share of the major players hardly moved, with CBA the largest owner occupied lender and Westpac still holding the largest portfolio of investment loans.

The market share of the major players hardly moved, with CBA the largest owner occupied lender and Westpac still holding the largest portfolio of investment loans.

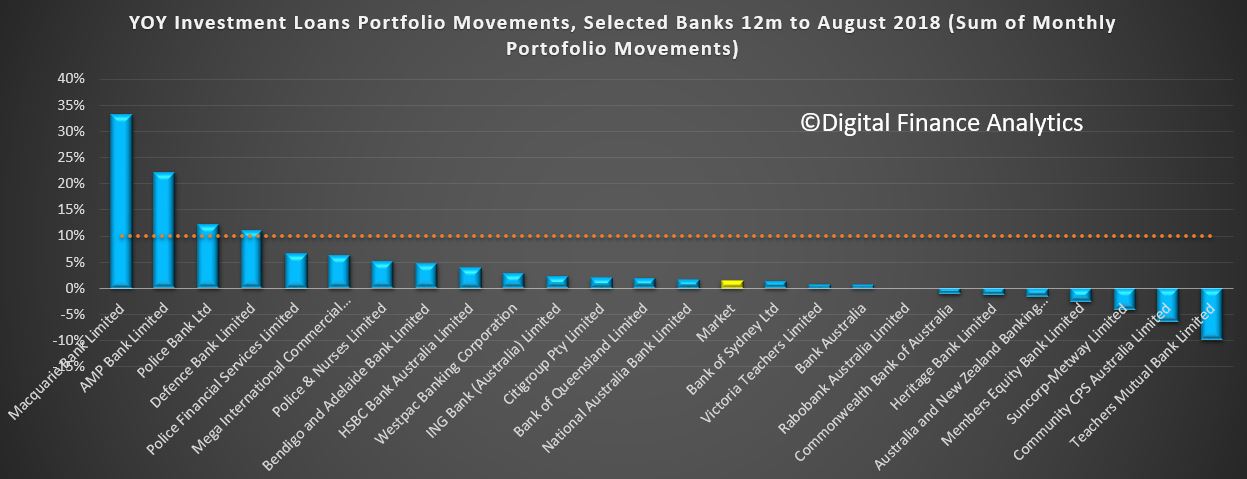

Whilst officially the 10% speed limit on investor loans has been sidelined, it is worth observing that over the past year, Macquarie, AMP and some of the smaller players are running way ahead of the market rate of growth.

Whilst officially the 10% speed limit on investor loans has been sidelined, it is worth observing that over the past year, Macquarie, AMP and some of the smaller players are running way ahead of the market rate of growth.

The RBA will post their aggregates later this morning, and we will then have a market view – and we can impute the non-bank lender share which we expect to be higher again.

The RBA will post their aggregates later this morning, and we will then have a market view – and we can impute the non-bank lender share which we expect to be higher again.

But for now it is worth highlighting that despite all the grizzles from the property spruikers, mortgage lending is STILL growing…. and faster than inflation. We have not tamed the debt beast so far, despite failing home prices. No justification to ease lending standards – none.

The Federal budget status moving towards a technical surplus earlier (remember this is new debt, not the total outstanding debt…) may take the risk premium on Australia down a tad, but I still expect higher mortgage rates ahead – not least as the banks struggle to fund the fallout from the various legal claims and penalties which are being, and will be imposed; to say nothing of higher international funding costs.

APRA has released some information relating to their 2017 stress tests in their “APRA Insight Issue Three 2018“. We discussed the results in a recent Adams/North video. We were not impressed!

This is what APRA has now released. Compared with the bank by bank data the FED releases, its VERY high level!

Stress testing plays an important role for both banks and APRA in testing financial resilience and assessing prudential risks. This article provides an overview of APRA’s approach to stress testing, with insights into how APRA developed the 2017 Authorised Deposit-taking Institution (ADI) Industry Stress Test. This builds on the recent speech by APRA Chairman Wayne Byres, “Preparing for a rainy day” (July 2018), which outlined the results from the 2017 exercise.

Why stress test

The aim of stress testing is, broadly, to test the resilience of financial institutions to adverse conditions, including severe but plausible scenarios that may threaten their viability. The estimation of the impact of adverse scenarios on an entity’s balance sheet provides insights into possible vulnerabilities and supports an assessment of financial resilience. It can be a key input into capital planning and the setting of targets, and in developing potential actions that could be taken to respond and rebuild resilience if needed.

Stress tests are particularly important for the Australian banking system, given the lack of significant prolonged economic stress since the early 1990s. As a forward-looking analytical tool, stress testing can help to improve understanding of the impact of current and emerging risks if a downturn were to occur. Stress tests provide an indication, however, rather than a definitive answer on the impact of adverse conditions, and the results will always reflect the inherent uncertainty that exists in any scenario.

Scenarios – the starting point

The starting point in developing a stress test is to design the scenarios. This is the foundation of the exercise, and it is important that scenarios are calibrated effectively and are well targeted. For industry stress tests, APRA collaborates with both the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) on the design of scenarios and the economic parameters that define them. In 2017, APRA also engaged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) in the design of the operational risk scenario.

Scenarios should be aligned to the purpose of the exercise. At a high level, these are guided within APRA by several objectives – namely to:

- assess system-wide and entity-specific resilience to severe but plausible scenarios;

- improve stress testing capabilities across the industry; and

- support the identification and assessment of core and emerging risks.

In line with these objectives, APRA developed two scenarios for the 2017 industry stress test. The first was a macroeconomic scenario with a China-led recession in Australia and New Zealand. This was considered the most severe but plausible adverse economic scenario for the banking system at the time.[1] In this scenario, there was assumed to be a fall in Australian GDP of 4 per cent, while house prices declined 35 per cent nationally over three years. The chart below provides an indication of the severity of the scenario: it shows that the assumed peak unemployment rate in the scenario was similar to the 1990s recession in Australia, the United States’ experience in the global financial crisis (GFC), as well as recent overseas regulatory stress tests.

The second scenario involved the same macroeconomic parameters, with an additional operational risk event added. This was designed to test bank resilience beyond traditional economic risks and to consider other vulnerabilities. In this operational risk scenario, APRA asked the participating banks to identify a material operational risk event involving conduct risk and/or mis-selling in the origination of residential mortgages.[2]

The banks chosen for the exercise were selected based primarily on scale, enabling a clear system-wide view to be generated. The 2017 stress test covered 13 of the largest banks with aggregate assets of nearly 90 per cent of the system, as well as the leading lenders mortgage insurers. It included both the major banks and smaller entities that have a significant presence in particular regions or asset classes.

The testing process

The 2017 stress test was run in two phases. In the first phase, banks generated results using their own stress testing methodologies and models.[3] The results of this phase varied by differences in the risk characteristics of each bank, as well as by how they interpreted and modelled the scenarios.

In the second phase, APRA provided more prescription with specified risk estimates for loan portfolios and other assumptions. This enabled greater comparability across the banks and more consistency in the results. The APRA estimates were developed based on the banks’ results from the first phase, APRA’s own internal modelling, historic and peer stress testing benchmarks, internal and external research and expert judgement.

The estimates were also differentiated based on inherent risk characteristics. For example, riskier interest-only loans were assumed to be more likely to default and losses were estimated to be greater for loans with higher Loan to Valuation Ratios (“LVRs”). For the operational risk scenario, APRA defined key elements and estimates to be applied by the banks, based on research of overseas experience as benchmarks for potential impacts.

Interpreting the results

The table below summarises some key results from the macroeconomic scenario. As important as the quantified outcomes are the lessons learned and implications of the exercise. Stress testing should not be an academic exercise, but should be used to inform assessments of resilience, risks and capacity to respond to stress.

In analysing the results, APRA assessed not only the impact on capital, but also the effects on profitability and loan portfolios. The differences between phase 1 (based on bank’s own modelling) and phase 2 (based on APRA risk estimates) can also shed light on bank stress testing modelling capabilities.

Macroeconomic scenario – aggregate results Phase 1 Phase 2 Peak to trough decline in Common Equity Tier 1 capital -2.87% -3.21% Peak to trough decline in Return on Equity -9.86% -12.05% Peak credit loss rate[4] 0.81% 0.90% Macroeconomic scenario

Given the design of the scenario, the impact on the participating banks was material. The results show that in this scenario the decline in profitability was severe and occurred quickly. Return on equity (ROE) in aggregate fell materially in the first two years before recovering after year three. The impact on profitability led to a significant fall in capital in both phases, as shown in Chart 3. There was, however, a wide range in results across banks in both phases.[5]

The losses were driven by bad debts in residential mortgage lending, corporate lending and other credit portfolios, as well as lower net interest income and losses on large single counterparties. Across the mortgages portfolios of the banks, aggregate losses were similar in both phases and although the mortgage portfolio contributed the largest aggregate loss, the loss rate was lower than business lending and other consumer lending portfolios.[6] The banks also modelled the impact of the scenario on liquidity and funding positions; most banks were able to maintain their liquidity with a liquidity coverage ratio (LCRs) above 100 per cent (or initiated strategies to restore their LCR within a reasonable timeframe).

In the second scenario, the impact of the operational risk event led to a more severe capital outcome, as shown in Chart 5. The operational risk events modelled by the banks in Phase 1 represented a wide range of potential risks, including broker fraud, inappropriate product design and sales practices, inappropriate verification and documentation, overstatement of valuation errors at origination, and serviceability errors. The impact of the operational risk event in Phase 2 based on APRA-defined assumptions was, however, more severe.

Following industry stress test exercises, APRA provides participating entities with formal feedback. In the 2017 stress test, APRA noted the importance of ongoing improvements in modelling capabilities and developing better internal model governance and discussions on results. In practice, a stress event is unlikely to play out exactly as designed and simulated in hypothetical scenarios, reinforcing the need to continue to stress test and enhance stress testing capabilities.

In APRA’s view, the results of the 2017 exercise provide a degree of reassurance: ADIs remained above regulatory minimum levels in what was a very severe stress scenario. In addition, the results were presented before taking into consideration management actions that would likely be taken to rebuild capital and respond to risks in the scenarios.[7] The impact on profitability, loan portfolios and capital would, however, be substantial: this underlines the importance of maintaining strong oversight and prudent risk settings, unquestionably strong capital and ongoing crisis readiness.

Footnotes

The chairman of APRA has suggested that digital distribution and servicing could threaten the existence of branch and broker networks.

The chairman of the prudential regulator, Wayne Byres, was speaking at the 2018 Curious Thinkers Conference in Sydney on Monday (24 September) when he outlined a “clash of predictions” for the future of the financial sector.

Stating that the pace of change “makes predicting the future difficult, and is why the crystal balls of even the most well informed are cloudy”, Mr Byres said that “everyone agrees major change is inevitable”.

Noting that it was “clear” that companies, regulators and international agencies are “all grappling to predict the impact that technology-enabled innovation will have on the structure of the financial sector and the viability of existing business models”, Mr Byres conceded that the “consensus also seems to be that it is too soon to tell whether the financial world faces evolution or revolution”.

Despite this, the chairman of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) told delegates that whatever the future scenario is, the “production and delivery of financial services will change”.

“Put simply, many traditional business models will no longer be competitive without significant change driven by technological investment,” Mr Byres said.

“Moreover, some incumbents will struggle to afford that investment; for others, the challenge will be successfully managing a large transformation program.”

Later in his speech, the APRA chairman forewarned that while most technological advancements in finance have previously “worked to enhance the market positioning of the major incumbents”, the future will “likely be different”.

Despite several futurists suggesting that brokers will survive digital disruption and others outlining that brokers will become more crucial in the future as trust in finance deteriorates, Mr Byres suggested that broker networks could be under threat in the future.

He stated: “New technologies have dramatically lowered barriers to entry. Cloud computing, for example, allows small organisations to operate innovative financial services without the need to maintain their own costly infrastructure and support staff.

“The advent of digital distribution and servicing removes the need for branch and broker networks.

“Open banking and comprehensive credit reporting will help new competitors to challenge established players. And, of course, regulators are making it easier to navigate the process of entry into the regulated financial system. Taken together, competition in the supply of financial services will only intensify.”

In conclusion, Mr Byres said that APRA’s role was to “make sure regulated entities are resilient and responsive to change, but not protected from it”, adding that while the regulator is responsible for promoting stability, “that does not mean standing in the way of change”.

He added: “Ensuring regulated entities are well managed, soundly capitalised and able to withstand severe stresses is designed to protect the interests of their depositors, policyholders or members.

“But to be clear, it is not APRA’s role to protect incumbent players when better, safer and more efficient ways of doing business emerge.

“Ultimately, we seek to look at it with a sharp focus on what is in the longer-run interests of their depositors, policyholders or members — not the business itself, or its owners — and make sure that boards and management are doing likewise.

“If that means their time is up, so be it. Our role then becomes ensuring they make an orderly exit from the industry.”

FBAA hits out at comments

The executive director of the Finance Brokers Association of Australia (FBAA), Peter White, hit out at the comments made by Mr Byres yesterday, telling The Adviser: “As it is, I certainly and completely disagree with this as being a current or near-term situation.”

The head of the FBAA highlighted that its research had recently showed that nearly 95 per cent of broker clients were satisfied with their broker, adding that more than half of the borrowing population uses a broker.

“So, digital distribution is not supported by fact,” Mr White said.

While the head of the FBAA suggested that digital home loans without any human intervention may be commonplace in 20 years’ time, he added that “we are a long way from this” in the near future.

Mr White told The Adviser: “For now, most people want to transact their home loan with a person, not a screen, and this won’t change for some time. Let alone the technical and legal barriers that still exist, the human element is still far more desired.”

In a shot across the bow, Mr White concluded: “So, for now (and once again), APRA seems to be out of touch with reality and people. Possibly they should be more so focused on their governance of ADIs given what we’ve all witnessed in the [banking] royal commission rather than out-of-focus speculation.”

APRA today published a letter relating to the Committed Liquidity Facility which is available to just 15 of the banks in Australia (The LCR banks). These have the back-stop option of calling on funds from the RBA to buttress their liquidity in case of need – so they can meet their obligations under the Basel III regime.

For a fee, if used, these banks essentially have a safety net in times of distress. Now APRA has outlined the arrangements for next year. Of course the other lenders have to operate without these supports.

For a fee, if used, these banks essentially have a safety net in times of distress. Now APRA has outlined the arrangements for next year. Of course the other lenders have to operate without these supports.

More evidence of a lack of a level playing field in the system, and how the regulators are supporting the big end of town. No surprise then that big players are regarded by the markets as too big to fail.

But as Australian Government debt is hurtling beyond $500 billion, I have to say their so called justification – lack of liquidity in the local securities (mainly Australian Government Securities and securities issued by the borrowing authorities of the states and territories) is wearing a bit thin.

Why is this facility needed at all?

This is what APRA said today:

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is today releasing aggregate results on the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) established between the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and certain locally incorporated ADIs that are subject to the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR).

APRA implemented the LCR on 1 January 2015. The LCR is a minimum requirement that aims to ensure that ADIs maintain sufficient unencumbered high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to survive a severe liquidity stress scenario lasting for 30 calendar days. The LCR is part of the Basel III package of measures to strengthen the global banking system.

In December 2010, APRA and the RBA announced that ADIs subject to the LCR will be able to establish a CLF with the RBA. The CLF is intended to be sufficient in size to compensate for the lack of sufficient HQLA (mainly Australian Government Securities and securities issued by the borrowing authorities of the states and territories) in Australia for ADIs to meet their LCR requirements. ADIs are required to make every reasonable effort to manage their liquidity risk through their own balance sheet management before applying for a CLF for LCR purposes.

Committed Liquidity Facility for 2019

All locally incorporated LCR ADIs were invited to apply for a CLF amount to take effect on 1 January 2019. All fifteen ADIs chose to apply. Following APRA’s assessment of applications, the aggregate Australian dollar net cash outflow (NCO) of the fifteen ADIs was estimated at approximately $381 billion. The total CLF amount allocated for 2019 (including an allowance for buffers over the minimum 100 per cent requirement) is approximately $243 billion.

| ($ billion) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Total forecast NCO | 410 | 402 | 400 | 387 | 381 |

| Available AGS and semis | 175 | 195 | 220 | 226 | 225 |

| Total CLF made available | 275 | 245 | 223 | 248 | 243 |

When this arrangement was announced in 2011 the RBA said:

The Committed Liquidity Facility

The CLF will enable participating ADIs to access a pre-specified amount of liquidity by entering into repurchase agreements of eligible securities outside the Reserve Bank’s normal market operations. To secure the Reserve Bank’s commitment, ADIs will be required to pay ongoing fees. The Reserve Bank’s commitment is contingent on the ADI having positive net worth in the opinion of the Bank, having consulted with APRA.

The facility will be at the discretion of the Reserve Bank. To be eligible for the facility, an ADI must first have received approval from APRA to meet part of its liquidity requirements through this facility. The facility can only be used to meet that part of the liquidity requirement agreed with APRA. APRA may also ask ADIs to confirm as much as 12 months in advance the extent to which they will be relying on a commitment from the Bank to meet their LCR requirement.

The Fee

In return for providing commitments under the CLF, the Bank will charge a fee of 15 basis points per annum, based on the size of the commitment. The fee will apply to both drawn and undrawn commitments and must be paid monthly in advance. The fee may be varied by the Bank at its sole discretion, provided it gives three months notice of any change.

Eligible Securities

Securities that ADIs can use under the CLF will include all securities eligible for the Reserve Bank’s normal market operations. In addition, for the purposes of the CLF, the Reserve Bank will allow ADIs to present certain related-party assets issued by bankruptcy remote vehicles, such as self-securitised residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS). This reflects a desire from a systemic risk perspective to avoid promoting excessive cross-holdings of bank-issued instruments. Should the ADI lack a sufficient quantity of residential mortgages, other ‘self-securitised’ assets may be considered, with eligibility assessed on a case-by-case basis.

The Reserve Bank has discretion to broaden the eligibility criteria and conditions for the various asset classes at any time. The Bank will provide one years notice of any decision to narrow the criteria for the facility.

Interest Rate

For the CLF, the Bank will purchase securities under repo at an interest rate set 25 basis points above the Board’s target for the cash rate, in line with the current arrangements for the overnight repo facility.

Margining

The initial margins that the Reserve Bank will apply to eligible collateral will be the same as those used in the Bank’s normal market operations. Consistent with current practice, each day the Bank will re-value all securities held under repurchase agreements at prevailing market prices.

Termination

Subject to the ADI having positive net worth, the Reserve Bank will give at least 12 months notice of any intention to terminate the CLF. The Bank’s commitment to any individual ADI will lapse if the fee is not paid.

APRA release their quarterly property exposure lending stats for ADI’s today. There are some interesting data points, and some concerning trends and loosening of standards recently. I will focus on the new loan flows in this post.

First the rise in loans outside serviceability continues to rise, now 6% of major banks are in this category a record, reflecting first tightening of lending standards, but second also their willingness to break their own rules! This should be ringing alarms bells. APRA?

Foreign Banks are writing the greater share (relative percentage) of 80-90% LVR loans. Other lenders tracking lower.

Foreign Banks are lending more 90+ LVR loans in relative percentage terms.

New investor loans are moving a little higher for Credit Unions and Major Banks, suggesting a growth in volumes.

The share of interest only loans dropped below 20% but is now rising a little, as lenders seek to grow their books.

ADIs’ residential term loans to households were $1.62 trillion as at 30 June 2018. This is an increase of $86.6 billion (5.6 per cent) on 30 June 2017. Of these:

- owner-occupied loans were $1,076.4 billion (66.4 per cent), an increase of $76.7 billion (7.7 per cent) from 30 June 2017; and

- investor loans were $544.0 billion (33.6 per cent), an increase of $9.9 billion (1.9 per cent) from 30 June 2017.

Note: ‘Other ADIs’ are excluded from all figures.

ADIs with greater than $1 billion of residential term loans held 98.9 per cent of all such loans as at 30 June 2018. These ADIs reported 5.9 million loans totalling $1.60 trillion. Of these:

- the average loan size was approximately $272,000, compared to $261,000 as at 30 June 2017 and

- $461.3 billion (28.8 per cent) were interest-only loans.

New housing loan approvals

On Wednesday 4 September, APRA chair Wayne Byres addressed the annual Risk Management Association CRO Conference in Sydney and spoke about regaining the community’s trust, via InvestorDaily.

“The broader community has lost confidence that the financial sector understands and acknowledges the privileged position that it holds in society, and the obligations that come with it,” said Mr Byres.

The chairman said that issues brought to light by the royal commission were now front and centre of the public’s consciousness and it was up to the industry to build the trust.

“It is not the regulators’ job to regain that trust for you: the industry needs to earn and sustain the community’s trust through its own actions.

“There are, however, a range of regulatory and supervisory activities that APRA is pursuing that will support and reinforce your own efforts to restore the industry’s standing,” he said.

Mr Byres reiterated his support for APRA to play a role in risk culture and said that APRA was primarily interested in what effects poor risk culture would have on the banks.

“APRA is primarily interested in the potential for a poor risk culture to produce bad outcomes for the bank (and hence depositors),” he said.

The prudential regulator is currently in a process of rescoping their pilot risk culture assessment to make it more useable on a wider basis, said Mr Byres.

“We don’t seek to prescribe the risk culture either. We expect executives and their boards to establish and maintain the risk culture that they consider (and note, we do expect a conscious consideration) to be appropriate to their organisations, given their strategy and risk appetite.”

Mr Byres said an important part of regaining trust was in the commencement of the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (BEAR) – but the work is far from over.

“The BEAR clearly has teeth, and use of the BEAR’s enforcement provisions will demonstrate to the community that there are going to be clear and material consequences for poor prudential outcomes.

“Where I hope the BEAR will have a positive impact is through forcing the industry to hold itself to account much more firmly and quickly than has been the case to date,” he said.

The last area that the APRA chairman flagged concerned remuneration. Mr Byres was keen to stress that APRA is not involved in determining who gets paid what.

Mr Byres said, instead, that APRA had reviewed remuneration policies throughout their entities and found that the frameworks across the board did not consistently meet the objectives of encouraging good behaviours.

“From insufficient challenge to insufficient documentation, it was clear that stronger governance of executive remuneration is needed,” he said.

Concluding his speech, Mr Byres said that if the industry worked together to improve risk culture, accountability and more balanced performance measurements, then the trust in the sector would return.

“As much as we might help, you will have to do the heavy lifting. It will ultimately be the industry’s collective behaviour that determines the extent to which the trust and confidence of the community is regained.”

The prudential regulator has defended its powers after the royal commission questioned its preference for working “behind closed doors” and failure to take legal action against rogue funds,via InvestorDaily.

The fifth round of the royal commission saw APRA deputy chair Helen Rowell grilled by counsel assisting Michael Hodge QC. Ms Rowell disagreed with Hodge’s suggestion that APRA works “behind closed doors” but admitted the that no corporate trustee has been required to give an enforceable undertaking in relation to superannuation in the last 10 years.

“The fact that no litigation was commenced does not mean that further remediation and proceedings are foreclosed,” APRA said in its submission. “APRA actively considered taking proceedings in the IOOF case.

“APRA accepts that there are legitimate questions as to whether a decision to litigate may achieve a result with wider deterrence effect as indicated in counsel assisting’s submissions. This issue will be the subject of further submissions by APRA on the policy and general questions posed by the commission following round 5.

“In APRA’s view, having the power to take litigation or other action is important to achieve the necessary changes and responses from entities without necessarily having to take that action in all cases. That is, the ‘threat’ of potential action facilitates the achievement of appropriate outcomes, which is APRA’s focus.”

APRA said the matter will be taken up further in its submissions on policy and general questions.

‘Fees for no service’

During her testimony on 17 August, Ms Rowell was asked whether APRA had received any suggestion from ASIC that ASIC will commence public enforcement action in relation to ‘fees for no service’.

“I don’t know the answer to that question,” Ms Rowell said.

In its submission, APRA agreed that charging fees for no service or charging fees to deceased members was “unacceptable”.

“However, what the most appropriate response is will depend on the context of the particular event,” APRA said.

“Where for example an RSE licensee itself identifies an instance of inappropriately charged fees, reports it promptly to APRA and engages with the relevant regulator (whether that be ASIC or APRA) in developing a remediation plan, APRA’s focus will properly be on whether the remediation plan is sufficient and whether the RSE licensee has systems in place designed to prevent future breaches.

“On the other hand, where RSE licensees do not promptly acknowledge and remedy issues, APRA can rely on the possible breaches of s 52 or s 62 to press the RSE licensee to take appropriate remedial and preventative action.”

APRA said the issue of ‘fees for no service’ impacts on the regulatory spheres of both ASIC and APRA.

“The ultimate causes of action for the misconduct identified may be different as between ASIC and APRA, but they will have the same factual substratum. APRA and ASIC share information and coordinate their activities in relation to the issue of fees for no service. APRA does not agree that it is incumbent on it to act earlier or separately from ASIC in such matters, when ASIC action may be achieving the common regulatory objective of appropriate remediation to affected members and/or where there may be other actions in train.”