The latest World Economic Outlook warns of slower growth though sees a possible acceleration later in the year (thanks to the Fed’s recent change in tune!).

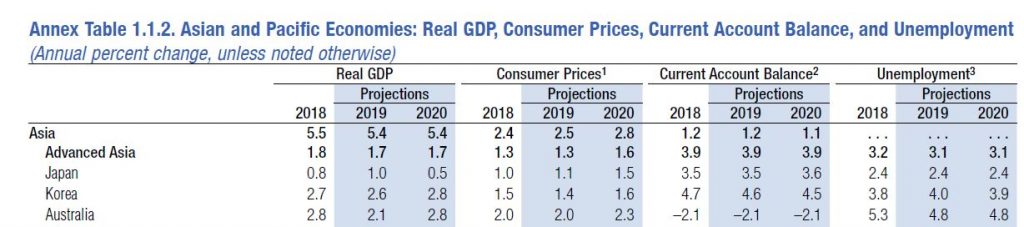

Australian growth is forecast to fall to 2.1% in 2019, with CPI at 2% and unemployment at 4.8%. In 2020, GDP is forecast at 2.8%, CPI 2.3% and unemployment at 4.8%.

One year ago economic activity was accelerating in almost all regions of the world and the global economy was projected to grow at 3.9 percent in 2018 and 2019.

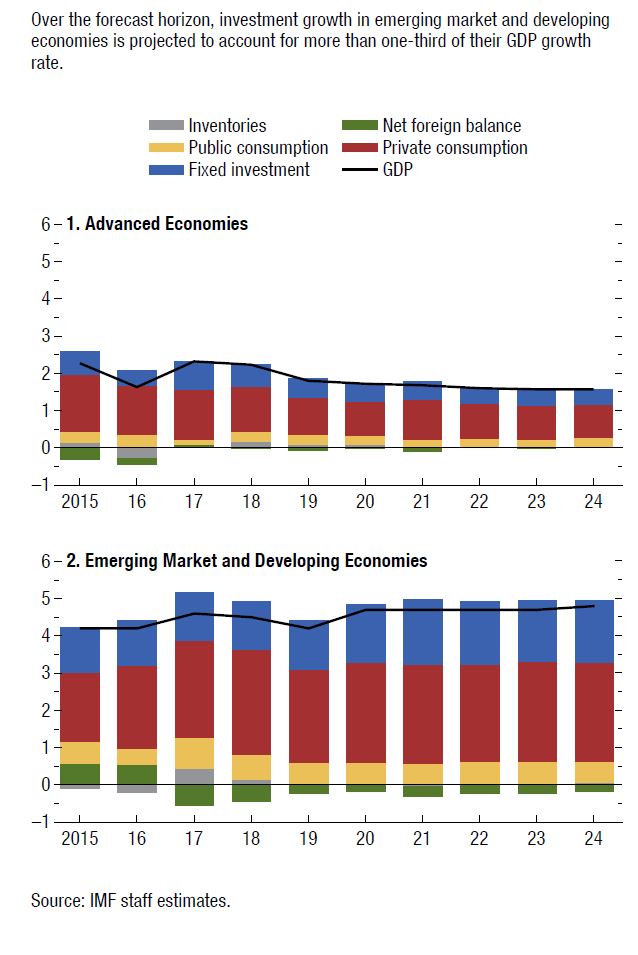

One year later, much has changed: the escalation of US–China trade tensions, macroeconomic stress in Argentina and Turkey, disruptions to the auto sector in Germany, tighter credit policies in China, and financial tightening alongside the normalization of monetary policy in the larger advanced economies have all contributed to a significantly weakened global expansion, especially in the second half of 2018. With this weakness expected to persist into the first half of 2019, the World Economic Outlook (WEO) projects a decline in growth in 2019 for 70 percent of the global economy. Global growth, which peaked at close to 4 percent in 2017, softened to 3.6 percent in 2018, and is projected to decline further to 3.3 percent in 2019. Although a 3.3 percent global expansion is still reasonable, the outlook for many countries is very challenging, with considerable uncertainties in the short term, especially as advanced economy growth rates converge toward their modest long-term potential.

While 2019 started out on a weak footing, a pickup is expected in the second half of the year. This pickup is supported by significant policy accommodation by major economies, made possible by the absence of inflationary pressures despite closing output gaps. The US Federal Reserve, in response to rising global risks, paused interest rate increases and signaled no increases for the rest of the year. The European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England have all shifted to a more accommodative stance. China has ramped up its fiscal and monetary stimulus to counter the negative effect of trade tariffs. Furthermore, the

outlook for US–China trade tensions has improved as the prospects of a trade agreement take shape. These policy responses have helped reverse the tightening of financial conditions to varying degrees across countries.

Emerging markets have experienced a resumption in portfolio flows, a decline in sovereign borrowing costs, and a strengthening of their currencies relative to the dollar. While the improvement in financial markets has been rapid, those in the real economy have yet to materialize. Measures of industrial production and investment remain weak for most advanced and emerging economies, and global trade has yet to recover. With improvements expected in the second half of 2019, global economic growth in 2020 is projected to return to 3.6 percent. This return is predicated on a rebound in Argentina and Turkey and some improvement in a set of other stressed emerging market and developing economies, and therefore subject to considerable uncertainty. Beyond 2020 growth will stabilize at around 3½ percent, bolstered mainly by growth in China and India and their increasing weights in world income. Growth in advanced economies will continue to slow gradually as the impact of US fiscal stimulus fades and growth tends toward the modest potential for the group, given ageing trends and low productivity growth. Growth in emerging market and developing economies will stabilize at around 5 percent, though with considerable variance between countries as subdued commodity prices and civil strife weaken prospects for some.

While the overall outlook remains benign, there are many downside risks. There is an uneasy truce on trade policy, as tensions could flare up again and play out in other areas (such as the auto industry) with large disruptions to global supply chains. Growth in China may surprise on the downside, and the risks surrounding Brexit remain heightened. In the face of significant financial vulnerabilities associated with large private and public sector debt in several countries, including sovereign-bank doom loop risks (for example, in Italy), there could be a rapid change in financial conditions owing to, for example, a risk-off episode or a no-deal Brexit.

With weak expansion projected for important parts of the world, a realization of these downside risks could dramatically worsen the outlook. This would take place at a time when conventional monetary and fiscal space is limited as a policy response. It is therefore imperative that costly policy mistakes are avoided. Policymakers need to work cooperatively to help ensure that policy uncertainty doesn’t weaken investment. Fiscal policy will need to manage trade-offs between supporting demand and ensuring that public debt remains on a sustainable path, and the optimal mix will depend on country-specific circumstances. Financial sector policies must address vulnerabilities proactively by deploying macroprudential tools. Low-income commodity exporters should diversify away from commodities given the subdued outlook for commodity prices. Monetary policy should remain data dependent, be well communicated, and ensure that inflation expectations remain anchored.

Across all economies, the imperative is to take actions that boost potential output, improve inclusiveness, and strengthen resilience. A social dialogue across all stakeholders to address inequality and political discontent will benefit economies. There is a need for greater multilateral cooperation to resolve trade conflicts, to address climate change and risks from cybersecurity, and to improve the effectiveness of international taxation.