Steve Mickenbecker from Canstar and I discuss the complexity of health insurance

Category: Health Insurance

Private Health Insurance Is Sick

The ACCC just released their 21st report into the Private Health Insurance Sector, which analyses key competition and consumer developments and trends in the private health insurance industry to 30th June 2019 that may have affected consumers’ health cover and out-of-pocket expenses. This report also continues the ACCC’s focus on adequate private health insurer

communications to their consumers, including on detrimental policy changes, as well as potential emerging issues in the use of consumer data.

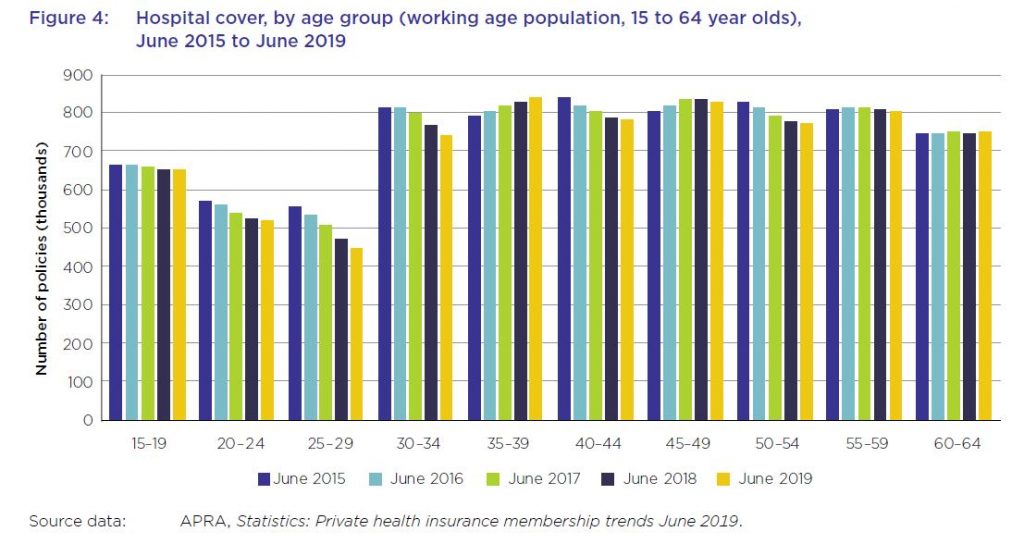

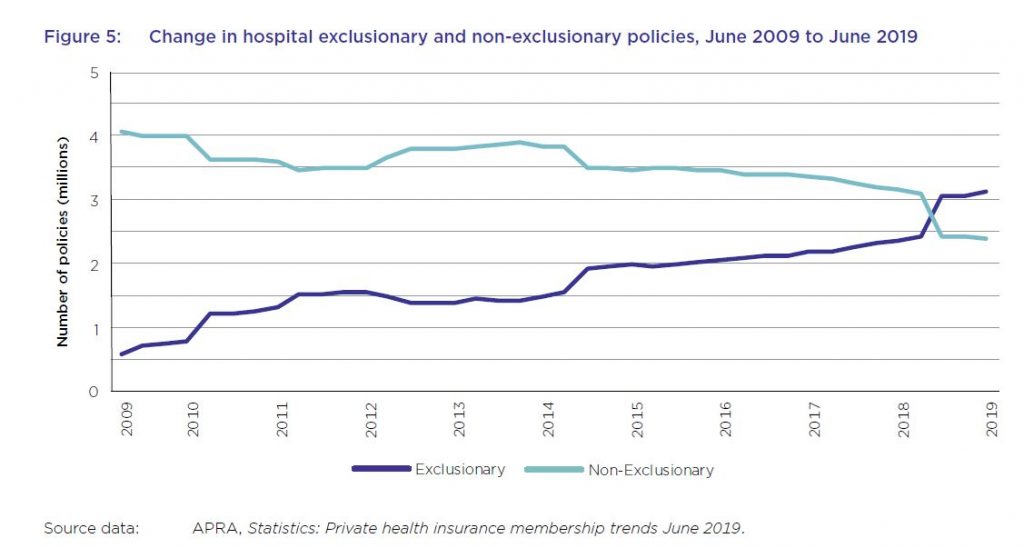

And in summary the system is unwell. Private health insurance premiums rise faster than income despite growing exclusions. For the first time, the majority of hospital treatment policies held by Australians now contain exclusions with more than 57 per cent of policies containing exclusions, up from about 44 per cent in the previous year. This chimes with our household surveys which shows more younger people are jettisoning their policies, or not signing up in the first place. This is a wicked problem, as more sick people as a total proportion are within the system, meaning that costs are becoming more concentrated.

Plus, the ACCC notes that consumer data collected by private health insurers and other businesses, for example through wellbeing apps and rewards schemes, can be used for a number of purposes such as targeted marketing, including from third parties.

Key industry data used and relied upon by the ACCC includes industry statistics and data collected by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and private health insurance complaints data from the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO).

As at 30 June 2019, 13.6 million Australians, or 53.6 per cent of the population, had some form of private health insurance. This represents a membership reduction of 0.6 per cent from June 2018 (54.2 per cent). The Australian population grew by 396 722, or almost 1.6 per cent, during this period. The decline is sharpest among younger age groups.

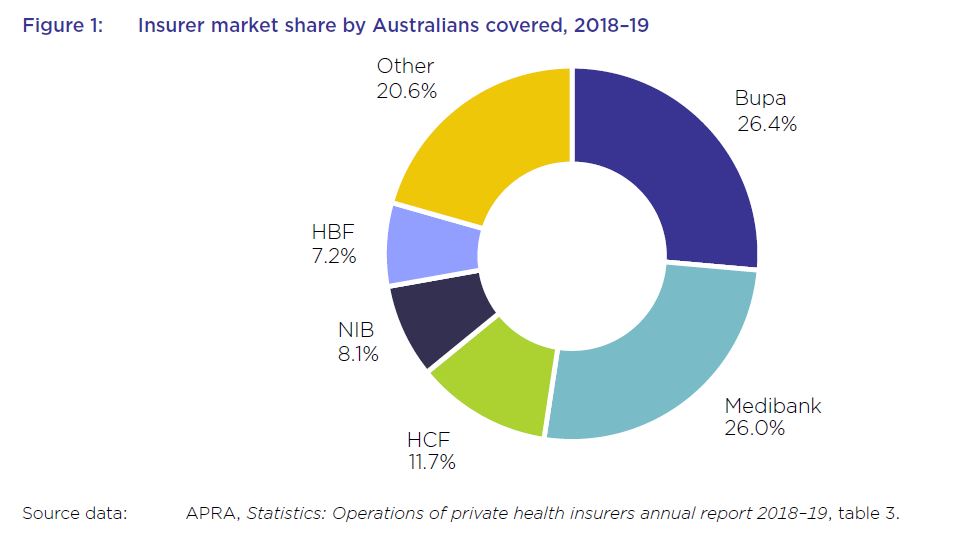

The five largest health insurers have a combined market share of almost 79.5 per cent and contributed to almost 77.5 per cent of total health fund benefits paid in 2018–1915, with Bupa and Medibank contributing 26.7 per cent and 25 per cent respectively.

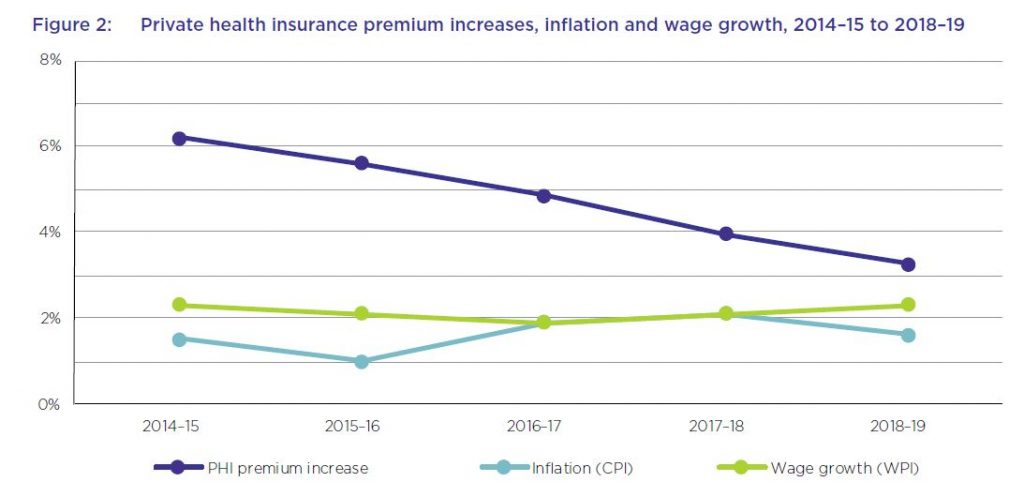

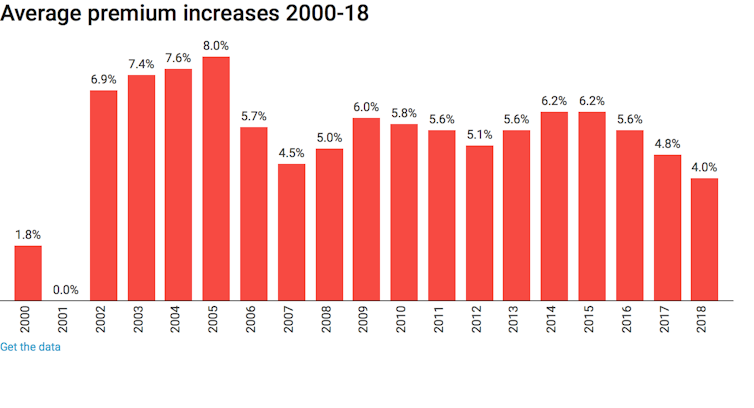

The average premium increase of 4.8 per cent per year over this period has been higher than the average annual growth in the wage price index (2.1 per cent) and the consumer price index (1.6 per cent) over the same period. While the rate of the average yearly premium increases has been decreasing each year over the past five years, and was 3.25 per cent in 2018–19, the average industry premium change for 2020, to take effect on 1 April 2020, will be 2.92 per cent – still well above wages growth.

From June 2018 to June 2019, the proportion of hospital policies held with exclusions increased by almost 14 per cent. For the first time, the majority of policies held now have exclusions.

The number of exclusionary policies held increased by over 650 000 from June 2018 to September 2018, with an equivalent reduction in non-exclusionary policies during the same period. APRA’s statistics did not indicate the reasons for this rise in the number of exclusionary policies during the reporting period. However, analysis by Silvester and others has suggested that less expensive exclusionary policies may appeal both to existing policyholders whose policies have become unaffordable, as well as to young people buying health insurance to avoid LHC loading and the

Medicare levy surcharge.

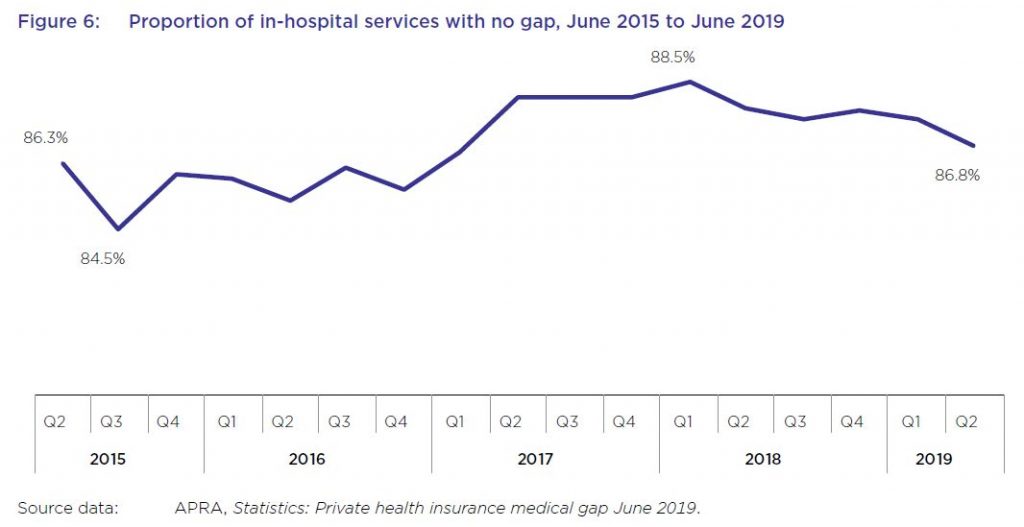

While most in-hospital services are delivered with no gap payments required from patients, this rate has varied in recent years, from a low of less than 85 per cent of services not requiring a gap payment in September 2015, to almost 89 per cent in March 2018, before falling again to under 87 per cent in June 2019.

From June 2018 to June 2019, the average gap expense incurred by a consumer for hospital treatment was $314.51, an increase of 1.9 per cent from the previous year, as shown in table 8. Average gap payments for extras treatment increased by almost 4 per cent to $49.20 over the same period.

A YouGov survey from late 2019 found that, after the cost of premiums and a perceived lack of value for money, out-of-pocket costs were a leading reason given by respondents for no longer holding private health insurance.

Several health insurers offer rewards schemes for their members, some of which involve the use of fitness tracking apps and devices to record activities such as steps and sleep. Some of these apps operate in conjunction with companies other than health insurers. For example, the health insurers MO Health and GMHBA are both partnered with the life insurer AIA Australia Limited, and use the AIA Vitality program issued by AIA.

HCF has also entered into a partnership with Flybuys where new HCF members can collect Flybuys points based on their annual health cover

premiums. Qantas, which offers health insurance issued by NIB, also offers frequent flyer points for members who download the Qantas Wellbeing app and undertake certain activities. Its Qantas Wellbeing Program Terms and Conditions state that members must link a tracking device to record their physical activity, and that as members, they consent to Qantas: “collecting, using and disclosing any personal information including health and Wellbeing information submitted by the Member through joining or use of the Wellbeing Program or collected by Qantas through the Tracking Device or the Qantas Wellbeing App”.

Although Australians can receive benefits from rewards and discounts offered by health insurers and other organisations that collect consumer data, the ACCC is concerned that few consumers are fully informed of, fully understand, or can effectively control, the scope of data collected when they sign up for, or use, such services.

While the community rating system for private health insurance in Australia prohibits insurers from charging different private health insurance premiums to individual consumers based on health and other

factors, the ACCC notes that the consumer data collected by wellbeing apps and rewards schemes could be used for a number of other purposes, including for targeted marketing (including from third parties), and potentially to create insights that could be shared with or sold to third parties.

The system will continue to be under pressure – and we think the model is frankly broken.

Bupa’s nursing home scandal is more evidence of a deep crisis in regulation

British health-care conglomerate Bupa runs more nursing homes in Australia than anyone else. We now know its record in meeting basic standards of care is also worse than any other provider. Via The Conversation.

This is more than a now familiar story of a corporation putting shareholders before customers. It is also about another abysmal design failure in regulation.

Health care is meant to be one of our most regulated sectors. In this case, Bupa’s facilities were inspected and certified by the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission.

The regulator’s inspectors found 45 of Bupa’s 72 nursing homes failed health and safety standards. In 22 homes the health and safety of residents was deemed at “serious risk”. Thirteen homes were “sanctioned” – with government funding being withheld and the homes banned from taking new residents.

Yet none of this appears to have spurred Bupa’s management into action, according to media reports. Flurries of inspection reports and written warnings over months and years only underlined that the regulatory tiger, even if it had teeth, had a very soft bite.

Responsive regulation

We have seen examples of equally insipid regulation in other areas. In the building sector, for example, a range of regulatory flaws including outsourced building certification have led to shoddily built and dangerous apartment construction.

In the financial sector, the banking royal commission castigated the industry regulators – the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority – for their unwillingness to enforce rules.

“The conduct regulator, ASIC, rarely went to court to seek public denunciation of and punishment for misconduct,” noted royal commissioner Ken Hayne. “The prudential regulator, APRA, never went to court.”

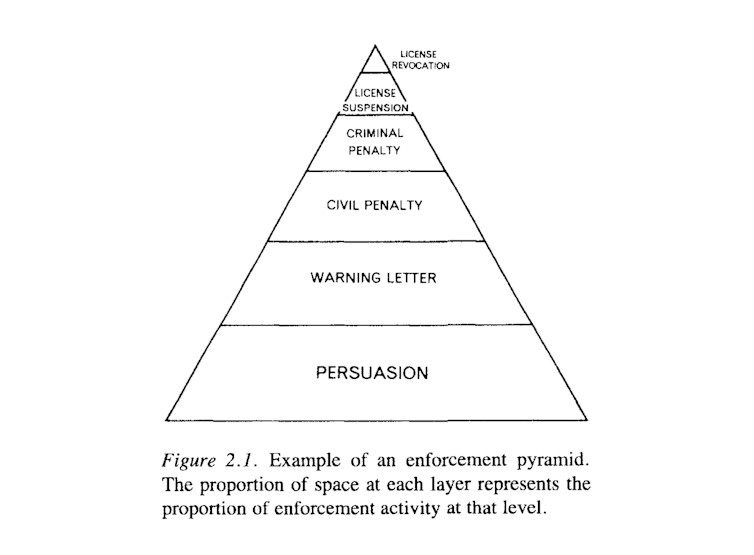

This failure is due to more than individual agency shortcomings. It’s an unintended consequence of the design of “responsive regulation” – the system that has superseded command-and-control regulation over the past three decades.

Responsive regulation was popularised by Australian sociologist John Braithwaite and American law professor Ian Ayres in the early 1990s. It was intended to overcome the pitfalls of the command-and-control model, which involved regulators employing large numbers of inspectors to look for non-compliance.

From about the 1970s it had become increasingly evident this model wasn’t working. It was also very expensive. Consider, for example, the cost of having fire and health and safety inspectors visit every single building site, particularly when most builders were doing the right thing. The cost and intrusiveness of the system fuelled calls to do away with regulation .

Too big to fail

Ayers and Braithwaite saw their model as a way forward. “Responsive regulation is not a clearly defined program or a set of prescriptions concerning the best way to regulate,” they explained. “On the contrary, the best strategy is shown to depend on context, regulatory culture and history.”

Responsive regulation assumes that in most cases the enterprises being regulated are interested in compliance and will respond to light-touch directives. It assumes that often compliance failures are due to ignorance or inadequate procedures. Its approach is to give parties a chance to amend their ways.

But there’s a potentially huge flaw in the responsive regulation model. What happens when an organisation is so large it is deemed too big to fail, or deems itself so?

This seems to have been the case with a number of financial companies whose misdeeds were exposed by the banking royal commission. It seems it might have been the case with Bupa.

In such cases, because of the timidity of the regulator or the confidence of the enterprise, the warnings might just go on and on. The company continues to book its profits – which may well eclipse any penalty it might have to pay if crunch time does ever come.

Markets have their limits

This design flaw highlights a more fundamental problem with governments positioning themselves as rule makers and leaving the rest to the “market”.

Markets are designed to facilitate exchange on the basis of profits. The profit motive means market participants look for the lowest-cost option. In aged care this means paying the lowest possible wages, possibly to unqualified staff, and cutting corners to cut costs.

Markets are very useful for increasing individual choices and efficiently allocating resources, but they are not suited to every task. They fail when factors other than profit ought to be considered.

We therefore need to think about the design of regulatory systems more holistically, as part of a broader social process.

The pioneers of responsive regulation certainly understood this. They emphasised flexibility, taking into account context, culture and history.

What those three things now tell us, given widespread regulatory failure across industries, is that government should not resist stepping in to provide important public services where the private sector cannot or will not do so at an acceptable level. Nor should it be afraid to act through empowered regulators, with ressources and powers to fulfil their mandates.

Author: Author: Benedict Sheehy, Associate professor, University of Canberra

Australians exiting private health insurance as price rises bite

The ACCC says many people are either abandoning their private health insurance policies or downgrading to lower-cost, lower-benefit products as premium increases continue to outpace inflation and wage growth.

In its annual report into the private health insurance industry, the ACCC found Australians are increasingly dropping their hospital cover, instead opting for just extras cover. Many people are also choosing policies with higher excess payments in an attempt to keep policy premiums to a minimum.

“People are increasingly feeling the pinch of private health premium increases and growing gap payments. In response, many are shifting to cheaper products with reduced coverage, and some are dropping their cover altogether,” ACCC Deputy Chair Delia Rickard said.

The affordability of private health insurance has been an increasing concern for consumers in recent years.

Many insurers will be updating their policies ahead of the Australian Government’s private health insurance reforms, which aim to make private health insurance simpler and more affordable, and come into effect on 1 April 2019.

The ACCC is warning private health insurers they must provide clear, prominent and timely communication with customers regarding changes.

“Private health funds have clear obligations not to mislead their customers under the Australian Consumer Law. Failing to properly tell customers about cuts to their benefits or policies may be a breach of the law,” Ms Rickard said.

“Ahead of 1 April 2019, we will be monitoring to see how health funds are telling consumers about changes to their policies and benefits. Private health insurers need to be transparent about what is and isn’t included in their policies or risk losing their customers’ trust and ultimately, their business.”

A copy of the ACCC’s report is available at: Private health insurance report 2017-18

Key industry developments and trends in 2017-18:

- In 2017–18, consumers paid about $23.9 billion in private health insurance premiums, an increase of almost $834 million or 3.6 per cent from 2016–17.

- The amount of hospital benefits paid by health insurers was $15.1 billion and the amount of extras treatment benefits paid was $5.2 billion.

- In June 2018, 45.1 per cent of the Australian population held hospital-only or combined health insurance cover, a decrease of 0.9 percentage points from June 2017.

- The proportion of the population holding extras-only policies increased from 8.9 per cent in June 2017 to 9.2 per cent in June 2018.

- About 88 per cent of in-hospital treatments were delivered with no gap payments.

- The average out-of-pocket expenses from hospital treatment increased by 3.3 per cent. Extras treatment recorded a decline of 0.7 per cent.

- Consumers are also continuing to shift to lower cost policies with exclusions, or excess and co-payments. In June 2018, 44 per cent of hospital policies held had exclusions, compared with 40 per cent in June 2017. There was also an increase in hospital policies with an excess or co-payment from 83 per cent to 84 per cent.

- Complaints to the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO) have decreased by 21 per cent since June 2017. The PHIO attributes this to improved complaint handling processes of larger insurers and the smaller premium increases in 2018 compared to recent years.

- Despite the decrease, the number of complaints received by the PHIO in 2017–18 is the second highest level recorded over the past five years.

Private health funds must provide accurate disclosures about their policies including any changes to the benefits available under their policies. Funds are not exempt from regulation and can face significant penalties if they breach the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

Private health insurers and other health industry participants have been the subject of a number of recent ACCC enforcement matters for alleged ACL breaches. The ACCC has recently finalised action against Australian Unity. Enforcement matters involving NIB and Ramsay Health Care are ongoing, and the ACCC’s appeal in the Medibank matter is awaiting judgment.

Background

Each year, the ACCC is required by the Senate to produce a report on key competition and consumer developments and trends impacting on people’s health cover. This report covers the 2017–18 period.

This is the ACCC’s 20th report to the Senate under this order.

Labor’s 2% cap on private health insurance premium rises won’t fix affordability

This week, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten announced a new private health insurance policy the Labor Party will take to the next election. First, Labor will get the Productivity Commission to conduct a full review of the private health insurance system. Second, and more controversially, Shorten promised a short-term 2% cap on premium increases for two years.

The promised cap is in response to consistently high premium increases of around 5% in recent years. In justifying the policy, Shorten said:

… the idea these big insurers are making record profits and yet the premiums keep going up and up, it can’t be sustained.

This announcement has already been greeted with scepticism and fury from the health insurance industry, with industry body Private Healthcare Australia branding the proposal “disastrous”.

As the proposal explicitly targets their profit margins, their response is predictable. However, in this case, they are right to complain. The premium cap policy is a crude measure that is unlikely to improve long-term affordability and may further distort the market in the short term.

Unintended consequences

Price controls introduced by governments usually have good intentions, but often have unintended consequences.

Consider, for example, the proposal to introduce caps on rent increases in the United Kingdom. Rent controls are among the most well-understood policies in economics: they reduce the quality and quantity of housing, leaving renters facing long search times to find housing and poorly maintained properties.

In health insurance, the most likely immediate response to the cap would be for insurers to increase the amount of exclusions – procedures and treatments that aren’t funded – and co-payments associated with policies.

So, while prices are kept low by the cap, consumers are effectively getting less coverage for their money. This would enable insurers to maintain their profit margins, but produce no gain, and further confusion, for consumers.

We already know the number of policies with exclusions, such as hip replacements and childbirth, has grown substantially. Labor’s proposal will probably accelerate the trend.

Long-term pain

Alternatively, as this proposed cap is time-limited, insurers may just put up with the pain of lower margins for a couple of years, with the timeline too short for significant changes to exclusions.

However, there may still be negative long-term impacts. We can look back in history for a clue about the long-term effects of a temporary cap on premiums. In 2000 and 2001, the Howard government implemented an effective “freeze” on private health insurance premium increases.

As can be seen in the graph, average premium increases were below 2% in 2000 (the largest insurer, Medibank Private, had a 0% increase in 2000), and were zero in 2001.

While consumers in 2000 and 2001 may have gained from lower real-terms premiums, we can see the long-term effects in the years from 2002 to 2005, when premium increases were between 7 and 8%. This is clearly an attempt by health insurance companies to “catch up” on the increases they missed in 2000 and 2001.

So, we may expect history to repeat itself if Labor wins the next election and introduces this policy: premiums will just rise faster in the years following the cap, negating any short-term benefit to consumers.

Why costs are rising

The proposed Productivity Commission review is much more promising in tackling important issues in the market, including lack of competition, confusing exclusions in policies, and its interaction with public funding through Medicare and public hospitals.

However, there is no solution to premium rises way in excess of general inflation if recent trends in healthcare technology and use continue. The number of hospital visits funded by private health insurance is growing strongly, at an average of 5.5% per year over the past five years.

Growth is across all areas of health care, from elective surgery like cataracts (4.9% a year) and hip replacement (5.5% a year) to diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy (4.4% a year) and life-saving cancer treatments like chemotherapy (5.5% a year).

We are paying more for our health insurance because we are using it more. No crude, short-term measures to restrict premium growth will deal with this fact. And good luck to the Productivity Commission in trying to reverse a global trend for higher private health care expenditure.

Author: Peter Sivey, Associate Professor, School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University

Increased private health insurance premiums don’t mean increased value

A topic of discussion at many barbecues this summer will inevitably be private health insurance. Is it worth it? Do we need it? Every year it gets more expensive. The average 4.8% increase in premiums just announced will have more Australians raising these questions, and debating with their friends how much they value choice of doctor, reduced waiting times for elective surgery, and having a private room when in hospital.

Private health insurance is mostly a private industry, but governments play a key role in ensuring private health insurance companies remain profitable and viable. Government policies encourage us all to have private health insurance by providing incentives for people to take out health insurance and imposing tax penalties for those on high incomes who do not have private health insurance.

Government makes decisions about pricing and funds the 30% rebate for many consumers with private health insurance. This is costing tax payers an estimated A$6 billion each year; money many economists argue is not justified and would be better spent in the public system.

Should the government have allowed this premium rise?

Each year private health insurance funds lobby the government to increase premiums. They claim increases are warranted because of an ageing population, increasing costs of health services and technologies, and decreasing government subsidies to consumers.

New federal health minister Greg Hunt has approved an average increase in premiums of 4.8%, with actual price hikes ranging from 2.9% up to 8.5%. This will mean families will pay up to $200 more per year, and singles up to $100 more each year.

The government argues this is the lowest premium increase in a decade. But this ignores the cumulative increase of 28% since 2012.

A premium that was $2000 in 2010 now costs about $3000. Many economists believe current premium increases, which are well over inflation rates, can’t be justified.

At a time when health insurance funds have increased profits, people are wondering about the value for money they get when they sign up for private health insurance.

Dissatisfaction on the issue was clearly on the political agenda in 2016, when previous health minister Sussan Ley announced a public consultation on private health insurance. This consultation made clear the concerns people have about poor value for money, high out of pocket costs, and complex regulations.

These issues have all been raised in our own research with consumers, and have been repeatedly raised by consumer organisations such as the Consumer Health Forum. Despite this consultation, it appears little has changed.

It is claimed Australians are paying more than ever for their private health insurance but are getting less and less. There are concerns about lack of transparency about what is covered, waiting periods and exclusions, and unexpected out-of-pocket costs.

Shifting responsibility to consumers

Each year when we discuss the premium price hikes, the concern is focused on how consumers, not industry, will react. The onus is often on consumers to be more aware, more active, and lobby for their needs. There are a range of sites dedicated to helping consumers make the best choice.

There is alarm that some people will drop their cover completely. But given the fear people have about needing private health insurance, there seems to be more consensus that people will reduce their level of cover rather than dropping it.

However, the risks of doing so are often not explored. Exposure to large and unexpected out of pocket costs, and as found in our research, the realisation (too late) that some procedures are not covered. When people do use their private health insurance they are likely to pay a gap, but these expenses are not clearly defined.

While there is a focus on people questioning the value of private health insurance, and whether these increased premiums are justified, there is very little questioning of how we might maximise the value of the public health care system.

For example, the outrage is not extended to the need to lobby government about strengthening the public health system, which is where most people, especially those who are poor and with complex health needs, end up.

Lots of arguments are made that the private health sector is important for a strong public system. In our research, it was evident some people view having private health insurance as helping out the health care system, and making space in the public system for people who cannot afford health insurance.

We know many Australians take out health insurance simply to avoid paying more tax through the Medicare levy surcharge. Some question whether they would rather be putting their money into Medicare than an industry they may choose never to use.

The federal government needs to implement greater protections for those who purchase private health insurance and ensure better value for the substantial funds taxpayers invest in private health insurance, directly and indirectly, through the private health insurance rebate, premiums, Medicare reimbursements and out-of-pocket costs.

Author: Associate Dean (Learning and Teaching), Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University; Lecturer, University of Sydney

New life insurance code riddled with loopholes

Life insurance has stood out as an industry without a code of practice when others such as general insurers have one. The latest attempt by the Financial Services Council to remedy this may be a last chance for life insurers to reform, before the government forces them to.

The code from the Financial Services Council focuses on the relationship between the insurer and the customer and aims at high standards of consumer service; professional behaviour and industry consistency. It should complement the legislation announced in 2015 to deal the problems of excessive up front premiums, remuneration practices and commissions which were incentives for insurers to churn customers through policies.

The code is also a result of the Trowbridge Report on retail life insurance which gave the life insurance industry a final opportunity to shape its future through a co-regulatory approach, rather than being reformed by the government alone.

Hopefully this latest attempt at reform does not go the same way as the earlier 1995 code of practice for the industry, which lapsed in 2001. This covered similar territory to the Financial Services Council code, but made little difference to the way the industry behaved. A positive sign is this new code was developed in consultation with industry, while the last one wasn’t.

What’s in the code?

This latest code will again try to address problems with selling practices and the quality of advice, high lapse rates, increases in premiums and their affordability as individuals age, and the redesign and repricing of products. The CommInsure scandal revealed further problems with outdated definitions and problems with making claims.

ASIC can approve these codes of practice for industry but rarely does so. This latest code is yet to be approved as well.

Some sectors have agreed to codes to forestall unwanted legislative change. Other codes establish higher standards of behaviour than required by law.

Codes are legally binding between an enterprise and a customer. This is because when an enterprise agrees to abide by a code it forms a kind of contract on the basis of this promise.

The very first part of the latest code of practice states that the code is binding and commits the entity to the standards in the code. The framework of the code looks at types of business rather than types of product.

One big omission in the code, is that it does not cover superannuation fund trustees or financial advisers, unless they explicitly adopt the code. This means it doesn’t cover a group policy where it is the employer or the superannuation fund trustee who has taken out the policy. As a result many Australians with life insurance within their super funds do not benefit at all from the code.

It does however apply to life products such as death, total and permanent disability, critical illness, disability, funeral, income protection, business expense and consumer credit insurance. But it does not cover products issued by a general insurer or a health insurer. This could create some confusion, for example it means that consumer credit insurance is covered by the code if provided by a life insurer, but not if provided by a general insurer.

Compliance with the code will be monitored by a Life Code Compliance committee. This is similar to the banking codes. The Financial Services Council and the insurers both have obligations to make consumers aware of the code.

Consumers can make a complaint using the code to the insurer, the Financial Ombudsman Service or Superannuation Complaints Tribunal. But if a complainant goes to a court, tribunal or other external dispute resolution body, the code no longer applies.

This code has an interesting take on the issue of designing life insurance products, as discussed in the 2014 Financial Systems Inquiry. It clearly states that when new policies are designed, “we will define suitable customers for the product”. This may stop the sale of products to those who don’t need them.

This is good but it still falls short of an obligation to sell a product that is suitable for the particular person, rather than a product that is generic for a class of targeted people. For example tailoring a policy to suit a person’s particular set of circumstances.

It’s a shame that the code has to set out that there will be rules to prevent sales to someone who is, “unlikely ever to be eligible to claim the benefits under a policy”. This really should be a part of the system already.

The obligation to review and update medical definitions is a good sign. But this applies only to policies that are currently being sold and won’t help those who are tied to policies with older definitions, that are no longer being sold.

The code also doesn’t have an obligation for insurers to disclose the exclusions in the policy, in plain language, to a customer before they sign a contract. This is something that really should be taken up by the industry.

Funeral insurance is the only life insurance product that requires a pre contract key fact sheet for offers. This type of disclosure shortcut is mandatory for home building and contents general insurance. Although there are difficulties inherent in simplification for key fact sheets this should be reconsidered for other life insurance products.

There are provisions for pre-sale disclosure for consumer credit insurance. Insurers are required to offer an alternative form of payment, when there is an offer of an initial loan to pay for insurance. In addition to this, insurers have an obligation to disclose the cost of loan repayments without and with the premiums and the interest payable on them. It may prevent some of the practices revealed in the reports on the problems of add-on insurance.

The code is a step towards a better relationship between the industry and consumers, particularly through the provisions to assist the vulnerable and helping customers make claims. It is not perfect.

The industry should continue to listen and take on board the virtues of the code. It can easily be changed to guide even better standards of conduct and meet newly identified problems.

Author: Gail Pearson, Professor, Business School, University of Sydney

ASIC probe finds insurance claims issues

From AAP via The West Australian.

The corporate regulator’s review into insurance has uncovered concerns about how claims are handled but no evidence of industry-wide misconduct.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission said on Wednesday that delays in claims handling and the evidence insurers require when assessing claims were the most common cause of disputes with customers.

The review of 15 insurers that make up 90 per cent of the industry showed that declined claim rates were highest for total and permanent disablement.

There were higher claims denial rates for insurance policies sold directly to consumers with no financial advice.

Some insurers had substantially higher than average declined claims rates and a substantially higher than proportionate share of disputes about claims.

However, nine out of 10 claims made on four major types of life insurance policy between 2013 to 2015 were paid out.

“While not finding evidence of cross-industry misconduct, ASIC’s review identified issues of conern in relation to higher claims denial rates and claims handling procedures,” ASIC said.

In a related probe, ASIC’s has obtained about 60,000 documents and has interviewed a range of people as part of its investigation into Commonwealth Bank’s CommInsure.

ASIC said it will work with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority and insurers over 2017 to establish a public reporting regime that details claims outcomes and dispute levels.

“To improve public trust, there is a clear need for better quality, more transparent and more consistent data on life insurance claims,” it said.

Industry Super Australia chief executive David Whiteley said the recommendations were a step in the right direction, but that government should ban all sales commissions on life insurance.

“Given the importance of life insurance to Australians, the government and industry need to ensure that financial advice is only in the interests of consumers and all conflicts of interests are removed,” he said.

Law firm Maurice Blackburn principal Josh Mennen said an enforceable code of conduct and a Royal Comission were the only credible options for reform.

“The report identifies that particular insurers remain a problem, but does not identify specific insurers against its findings,” he said.

“The public has a right to know who the worst offenders are.”

APRA To Regulate Private Health Insurers

The Treasury has today released an Exposure Draft that will establish APRA as the prudential regulator of the private health insurance industry. This is part of the Smaller Government – additional reductions in the number of Australian Government bodies initiative announced as part of the 2014-15 Budget. The Private Health Insurance Administration Council (PHIAC) will cease as a separate body and its prudential supervisory functions will be transferred to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). The transfer of PHIAC’s prudential supervisory functions will be given effect by the Exposure Draft Private Health Insurance (Prudential Supervision) Bill 2015 (Exposure Draft Bill) which will represent a new Act for the regulation of private health insurers, administered by APRA. The main changes are:

- the registration of private health insurers and the prevention of entities not registered from carrying on a health related business

- requirement for private health insurers to have health benefits funds and obligations relating to the operation of such funds

- restructure, merger, acquisition and termination of health benefits funds

- appointment of an external manager of a health benefit fund and the powers and duties of external managers and terminating managers

- duties and liabilities of directors

- establishment of prudential standards and directions by APRA and the requirements for health benefits funds to comply with such standards and directions

- obligations of private health insurers such as the appointment of actuaries and reporting and notification requirements

- APRA’s ability to supervise compliance by private health insurers with their obligations and APRA’s enforcement powers

- enforceable undertakings

- APRA’s ability to seek remedies for a contravention for an enforceable obligation

- review of APRA’s decisions by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

- ability of APRA to give approvals and make determinations and rules

Treasury is seeking feedback by 30th January.