RoboChat has been launched by the NAB-owned online bank as a “virtual assistant to help potential homebuyers and refinancers complete their online home loan applications” and “simplify the home loan application process”.

The new chatbot has been built by IBM Watson to act as a virtual assistant to aid customers through the home loan application form.

According to UBank, the bot — which is still “in training” — aims to “help reduce the time needed for customers to complete the form by offering on-the-spot help”.

It has been trained on data collected from customer questions submitted via UBank’s LiveChat experience, and has been tested by “dozens of users and iteratively trained”.

UBank has said that the bot’s artificial intelligence will “continue to learn as more customers engage with it, becoming smarter and more user-friendly over time”.

However, the bank has been emphatic on the fact that the bot “won’t affect the size of the local UBank customer service team or the great work they do”.

Speaking of the product, the CEO of UBank, Lee Hatton told The Adviser that RoboChat was created to help customers overcome the “fear of how long it will take to fill out the applications”.

When asked if the platform was meant to emulate what a broker does, Ms Hatton said: “RoboChat was designed specifically to guide customers through UBank’s online home loan application form.

“UBank doesn’t use mortgage brokers, so RoboChat, along with our experienced advisers, can help customers as they decide which home loan is right for them.”

Ms Hatton added that the chatbot is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week so can provide real-time answers, but customers can still use a bank adviser to assist with “more specific support or [questions] fitting to [an] individual situation”.

Putting RoboChat to the test

Once a user selects that it wants to start a home loan application, the RoboChat option opens up alongside the online application process. It is here that users can ask the bot questions. The website notes that once an application is completed (with questions answered), a home loan specialist will be in touch to move the process forward.

When first opened, the chatbot introduces itself as Ubank’s “beta virtual assistant”, adding that it is “still in training” and will “do [its] best to answer your home loan questions”. It says you can speak to a real person at any time.

The Adviser tested out the platform, and it successfully answered simple questions such as “What is your variable rate?’ (with that answer being 3.74 per cent) and “Do you have an offset?” (which it doesn’t), as well as “What are your charges?” (it doesn’t have any unless the loan is fixed rate) but struggled when the next question was a new subject (“Can I have an interest-only loan?”), responding that it was “wasn’t expecting that kind of response”.

However, once establishing that the user was still interested in interest rates, and ascertaining that the user was an owner-occupier, the bot asked if it was for principal and interest, or interest-only. Once interest-only was chosen, the bot produced the interest rates with comparison rates (4.13 per cent with the Real Reward Offer or 4.46 (4.39 per cent comparison) without).

When asked “Should I use a broker?” the RoboChat asked for the question to be rephrased. When asked “Do you have a broker?”, it said: “We’re an online bank so we don’t have branches, mobile lenders, or use brokers. The upside is we have fewer costs than traditional banks and we pass the savings onto you. Do you want to know more?”

It also understood “Can you tell me your LVR?”, but struggled with “What is your LVR?”, and didn’t understand “Can I refinance?” but knew the answer to “How do I refinance?”.

When asked “How much can I borrow?” RoboChat said: “I can’t perform calculations just yet” and offered links to tools and calculators.

The platform handled other questions, such as “I’m self-employed. Do you have a loan for me?”, responding “To ensure we’re a good match, your primary income needs to be from an Australian PAYG source of a company not owned by you. And, all applicants must be either an Australian citizen OR Australian Permanent Resident OR a NZ citizen AND reside in Australia. As a bank, we’ll always need to perform a credit assessment based on the details of each applicant.”

While the bank has said that it has in-built humour and offers “tongue-in-cheek responses”, the bot was not able to respond to the joke as outlined in the press release (“How much does a hipster weigh?” Answer: “An Instagram”), instead saying “Hmmmm, I’m a bit confused. Can you rephrase your question?” When asked for the meaning of life, it did say, however, “Simpler, better, smarter is my life motto!”

Ms Hatten commented: “Our goal is to deliver simpler, better, smarter banking to our customers and RoboChat will help deliver on this by streamlining the application form.

“RoboChat will be a very welcome addition to our team of customer service experts” continued Hatton.

“UBank will still have experienced staff on hand to chat on the phone, via email and our live online chat offering, RoboChat will provide an added option for those needing quick online responses or those that are close to finalising the form.”

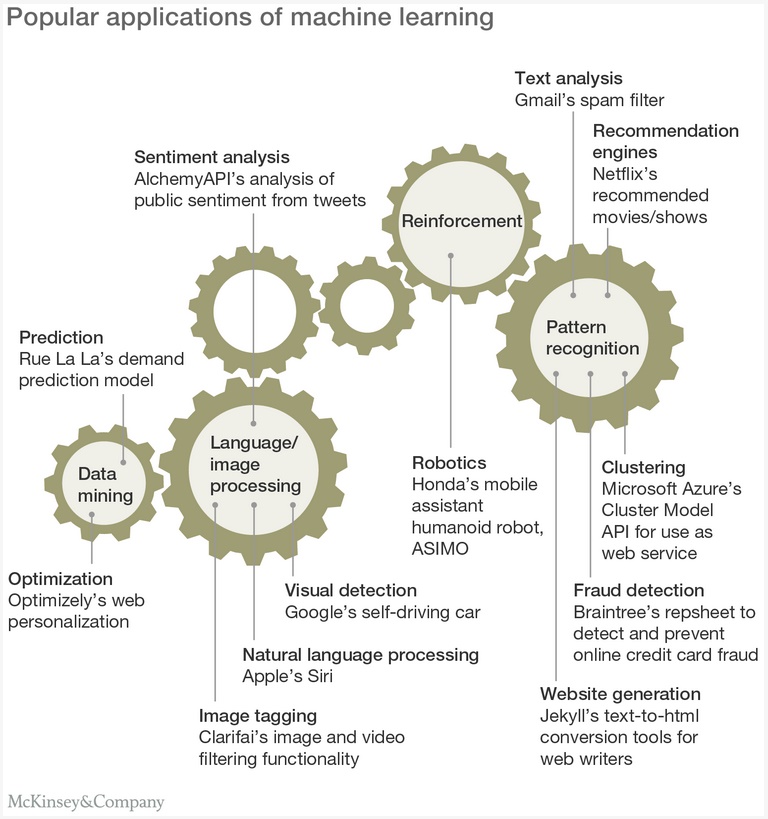

Brock Douglas, vice president of Watson for IBM Asia Pacific added: “From deepening the customer experience, to increased productivity for employees, virtual assistants are being adopted across industries and becoming more advanced in natural conversation and emotional intelligence, with the help of cognitive technology.

“UBank’s work with IBM Watson is a powerful example of how organisations are leveraging cognitive virtual assistants that have the ability to engage in a conversation, ask questions, learn and respond in context – as opposed to providing stock responses.”