The ECB’s quantitative easing programme is unlikely to materially boost eurozone banks’ earnings or kick-start lending in the bloc, Fitch Ratings says. But it does reduce downside risk from prolonged deflation. Any positive impact on banks is likely to be temporary unless their balance sheets are freed up for more lending or structural reforms raise real and sustainable economic growth.

We think QE is unlikely to stimulate lending in the eurozone’s crisis-hit economies, despite the start of rebalancing and recovery in some countries. The economic outlook is still fragile, so demand for credit is likely to remain subdued, and tighter regulatory requirements are making loan growth more difficult for banks.

Banks have to hold an increasing amount of regulatory capital against the loans they extend as Basel III rules are phased in. The bar is also being raised by the ECB in its role as the new single supervisor – it recently communicated its Pillar 2 expectations for buffer capital to each of the banks. They will also have to build debt and capital buffers to meet new total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) and minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) rules. Gearing up bank balance sheets through loan expansion runs contrary to these regulatory pressures.

Some banks may be able to generate more trading income, as the ECB’s accommodative policy should push down bond yields and encourage trading flow. Gains on any sales of sovereign bond holdings by banks are likely to be limited because yields have continued to fall in recent months. Any revenue benefits from sovereign bond sales and trading will probably be offset by lower margins from a flatter yield curve, so the balance is likely to be neutral or even slightly negative for profitability.

Many banks in northern Europe are already awash with liquidity, so lower bond yields would only distort credit pricing there even more. Weaknesses in some of the economies, such as Germany and France, which grew 1.2% and 0.4%, respectively, yoy in 3Q14, are likely to keep investment appetite, and therefore loan demand, muted, especially for good-quality corporates, despite even cheaper potential funding rates.

Southern European banks could benefit more from QE, but the impact would depend on the pricing of their sovereign debt portfolios and the extent to which these are booked as held-to-maturity assets. But there could be some rebalancing of sovereign debt portfolios and banks are likely to look to lock in some gains. Loan expansion is even less likely in southern Europe, as most banks there are still strengthening balance sheets, gradually reducing impaired loans and dealing with legacy assets.

If the ECB’s actions do not ward off deflation, eurozone banks would come under more pressure from dampening earnings, increasing non-performing loans and weakening collateral values.

Month: January 2015

Metadata – A Marketeer’s Dream Comes True

Next time you shop, and pay by credit card, consider this. According to a recent report “Unique in the shopping mall: On the reidentifiability of credit card metadata”, it is possible to take anonymous transaction data and by applying analytics to the data, uncover considerable information about the card holder, especially, when cross-matched with other data sources. More broadly, anyone who thinks retaining meta-data has no consequences, should read this report.

Metadata contain sensitive information. Understanding the privacy of these data sets is key to their broad use and, ultimately, their impact. We study 3 months of credit card records for 1.1 million people and show that four spatiotemporal points are enough to uniquely reidentify 90% of individuals. We show that knowing the price of a transaction increases the risk of reidentification by 22%, on average. Finally, we show that even data sets that provide coarse information at any or all of the dimensions provide little anonymity and that women are more reidentifiable than men in credit card metadata.

Large-scale data sets of human behavior have the potential to fundamentally transform the way we fight diseases, design cities, or perform research. Ubiquitous technologies create personal metadata on a very large scale. Our smartphones, browsers, cars, or credit cards generate information about where we are, whom we call, or how much we spend. Scientists have compared this recent availability of large-scale behavioral data sets to the invention of the microscope. New fields such as computational social science rely on metadata to address crucial questions such as fighting malaria, studying the spread of information, or monitoring poverty. The same metadata data sets are also used by organizations and governments. For example, Netflix uses viewing patterns to recommend movies, whereas Google uses location data to provide real-time traffic information, allowing drivers to reduce fuel consumption and time spent traveling.

The transformational potential of metadata data sets is, however, conditional on their wide availability. In science, it is essential for the data to be available and shareable. Sharing data allows scientists to build on previous work, replicate results, or propose alternative hypotheses and models. Several publishers and funding agencies now require experimental data to be publicly available. Governments and businesses are similarly realizing the benefits of open data. For example, Boston’s transportation authority makes the real-time position of all public rail vehicles available through a public interface, whereas Orange Group and its subsidiaries make large samples of mobile phone data from Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal available to selected researchers through their Data for Development challenges.

These metadata are generated by our use of technology and, hence, may reveal a lot about an individual. Making these data sets broadly available, therefore, requires solid quantitative guarantees on the risk of reidentification. A data set’s lack of names, home addresses, phone numbers, or other obvious identifiers [such as required, for instance, under the U.S. personally identifiable information (PII) “specific-types” approach, does not make it anonymous nor safe to release to the public and to third parties. The privacy of such simply anonymized data sets has been compromised before.

Unicity quantifies the intrinsic reidentification risk of a data set. It was recently used to show that individuals in a simply anonymized mobile phone data set are reidentifiable from only four pieces of outside information. Outside information could be a tweet that positions a user at an approximate time for a mobility data set or a publicly available movie review for the Netflix data set. Unicity quantifies how much outside information one would need, on average, to reidentify a specific and known user in a simply anonymized data set. The higher a data set’s unicity is, the more reidentifiable it is. It consequently also quantifies the ease with which a simply anonymized data set could be merged with another.

Financial data that include noncash and digital payments contain rich metadata on individuals’ behavior. About 60% of payments in the United States are made using credit cards, and mobile payments are estimated to soon top $1 billion in the United States. A recent survey shows that financial and credit card data sets are considered the most sensitive personal data worldwide. Among Americans, 87% consider credit card data as moderately or extremely private, whereas only 68% consider health and genetic information private, and 62% consider location data private. At the same time, financial data sets have been used extensively for credit scoring, fraud detection, and understanding the predictability of shopping patterns. Financial metadata have great potential, but they are also personal and highly sensitive. There are obvious benefits to having metadata data sets broadly available, but this first requires a solid understanding of their privacy.

To provide a quantitative assessment of the likelihood of identification from financial data, we used a data set D of 3 months of credit card transactions for 1.1 million users in 10,000 shops in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country. The data set was simply anonymized, which means that it did not contain any names, account numbers, or obvious identifiers. Each transaction was time-stamped with a resolution of 1 day and associated with one shop. Shops are distributed throughout the country, and the number of shops in a district scales with population density.

For example, let’s say that we are searching for Scott in a simply anonymized credit card data set. We know two points about Scott: he went to the bakery on 23 September and to the restaurant on 24 September. Searching through the data set reveals that there is one and only one person in the entire data set who went to these two places on these two days. Scott is reidentified, and we now know all of his other transactions, such as the fact that he went shopping for shoes and groceries on 23 September, and how much he spent.

Furthermore, financial traces contain one additional column that can be used to reidentify an individual: the price of a transaction. A piece of outside information, a spatiotemporal tuple can become a triple: space, time, and the approximate price of the transaction. The data set contains the exact price of each transaction, but we assume that we only observe an approximation of this price with a precision a we call price resolution. Prices are approximated by bins whose size is increasing; that is, the size of a bin containing low prices is smaller than the size of a bin containing high prices.

Despite technological and behavioral differences, we showed credit card records to be as reidentifiable as mobile phone data and their unicity to be robust to coarsening or noise. Like credit card and mobile phone metadata, Web browsing or transportation data sets are generated as side effects of human interaction with technology, are subjected to the same idiosyncrasies of human behavior, and are also sparse and high-dimensional (for example, in the number of Web sites one can visit or the number of possible entry-exit combinations of metro stations). This means that these data can probably be relatively easily reidentified if released in a simply anonymized form and that they can probably not be anonymized by simply coarsening of the data.

Our results render the concept of PII, on which the applicability of U.S. and European Union (EU) privacy laws depend, inadequate for metadata data sets. On the one hand, the U.S. specific-types approach—for which the lack of names, home addresses, phone numbers, or other listed PII is enough to not be subject to privacy laws—is obviously not sufficient to protect the privacy of individuals in high-unicity metadata data sets. On the other hand, open-ended definitions expanding privacy laws to “any information concerning an identified or identifiable person” in the EU proposed data regulation or “[when the] re-identification to a particular person is not possible” for Deutsche Telekom are probably impossible to prove and could very strongly limit any sharing of the data.

From a technical perspective, our results emphasize the need to move, when possible, to more advanced and probably interactive individual or group privacy-conscientious technologies, as well as the need for more research in computational privacy. From a policy perspective, our findings highlight the need to reform our data protection mechanisms beyond PII and anonymity and toward a more quantitative assessment of the likelihood of reidentification. Finding the right balance between privacy and utility is absolutely crucial to realizing the great potential of metadata.

Urgent Action Required To Boost Business Lending

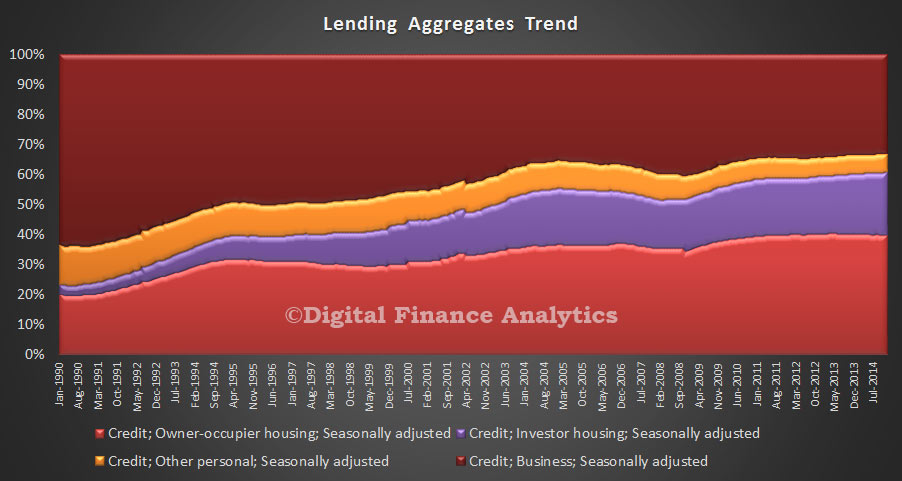

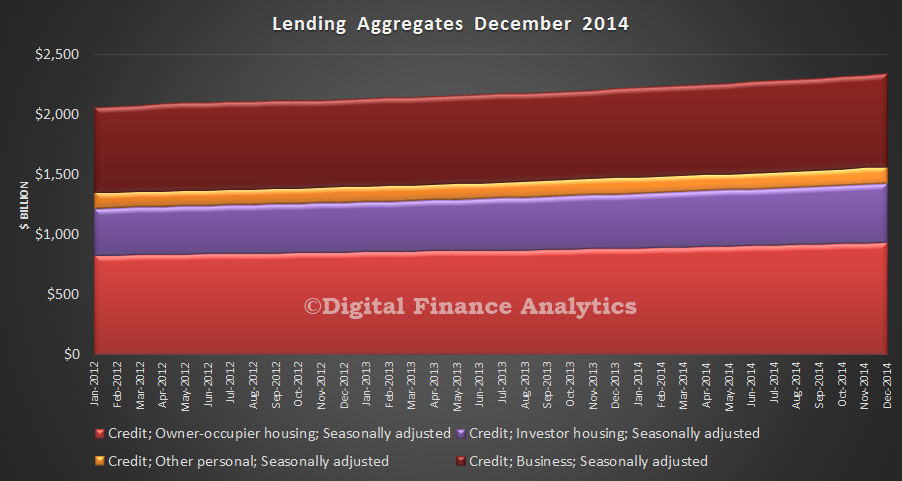

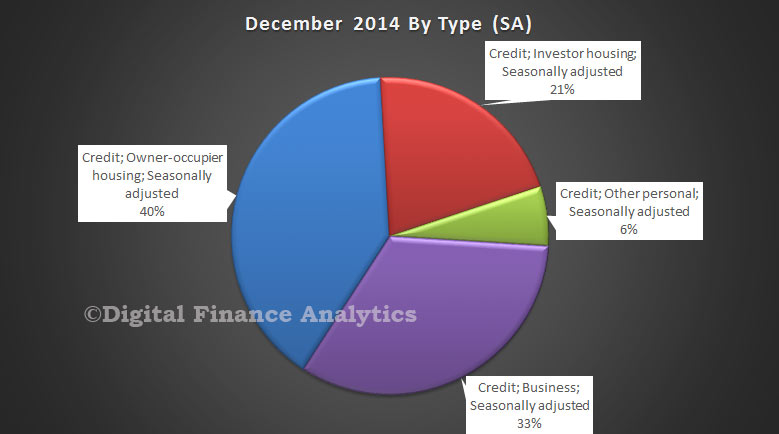

Today the data from RBA and APRA showed the strength of lending in the housing sector, and only 33% of lending is business related. This over-emphasis on property investment in particular is a systemic problem, and must be addressed if we are to drive growth in the right direction. Business needs more focus.

To illustrate the point, the mix between business lending and housing (both owner occupied and investment) is worth examining from 1990 onwards. Back then, business lending accounted for about 65% of all lending. Today it is 33%. As a result we know from our SME surveys that many businesses are finding it difficult to get funding on reasonable terms. On the other hand, we see lending for housing, and especially investment lending inflating the banks balance sheets and house prices, but this is not truly productive.

To illustrate the point, the mix between business lending and housing (both owner occupied and investment) is worth examining from 1990 onwards. Back then, business lending accounted for about 65% of all lending. Today it is 33%. As a result we know from our SME surveys that many businesses are finding it difficult to get funding on reasonable terms. On the other hand, we see lending for housing, and especially investment lending inflating the banks balance sheets and house prices, but this is not truly productive.

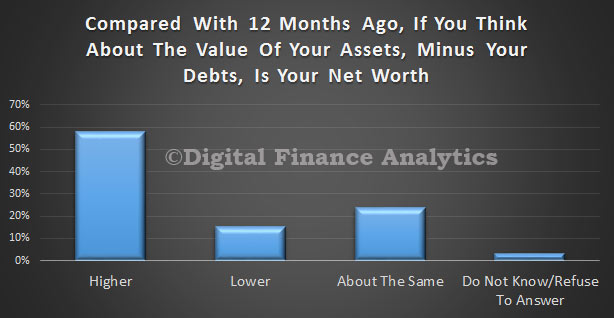

Its time to impose additional controls on investment lending, and to re-balance lending towards businesses who will be able to generate real economic growth for the country. The current situation, where household net worth grows…

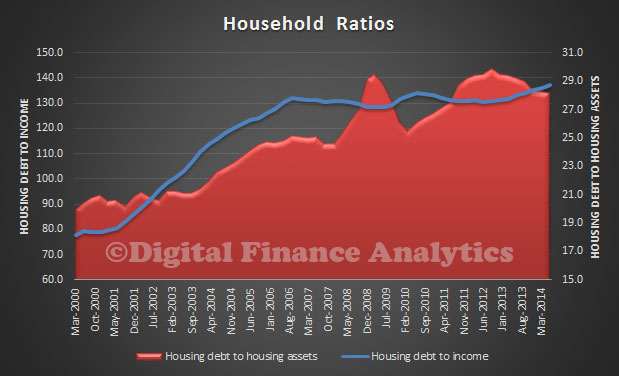

… thanks to over-high house prices is not sustainable when it is powered by ever more household debt.

… thanks to over-high house prices is not sustainable when it is powered by ever more household debt.

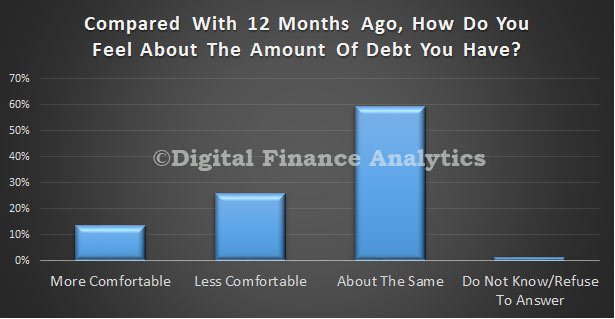

From our surveys, a quarter of households are less comfortable with the amount of debt they have compared with 12 months ago.

Any further interest rate cuts without these measures would be irresponsible.

Any further interest rate cuts without these measures would be irresponsible.

Home Lending Up To A Record $1.42 Trillion In December

The RBA released their credit aggregates for December 2014 today. Total credit grew by 5.9%, with housing recording 7.1%, Business 4.8% and Personal Credit 0.9% in annual terms. In the last month, housing lending grew 0.6% and business 0.5%.

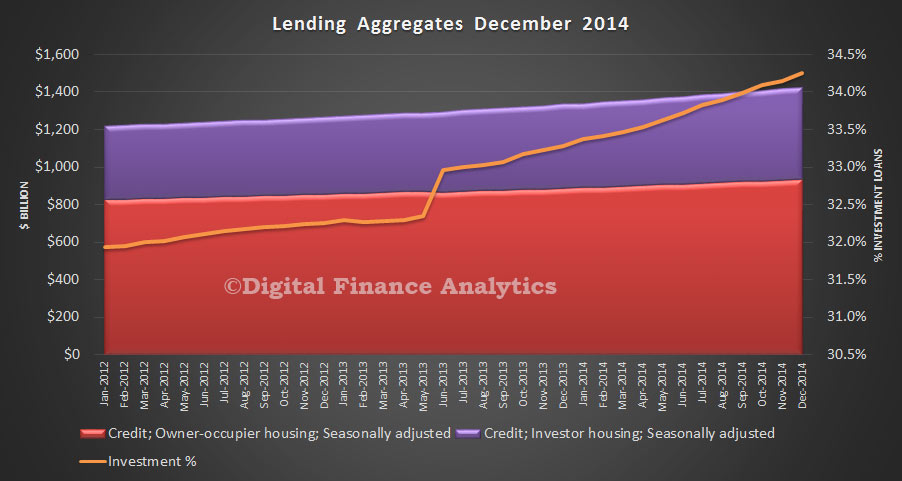

Looking at the breakdown, we see that housing lending grew apace, powered by further significant investment lending. Total housing lending reached a record $1.42 trillion, thanks to growth of $3.5 billion in owner occupied loans (up 0.38%) and investment lending of $4.2 billion (up 0.87%) in the month. Investment loans now make up 34.3% of home lending, another record.

Looking at the breakdown, we see that housing lending grew apace, powered by further significant investment lending. Total housing lending reached a record $1.42 trillion, thanks to growth of $3.5 billion in owner occupied loans (up 0.38%) and investment lending of $4.2 billion (up 0.87%) in the month. Investment loans now make up 34.3% of home lending, another record.

Overall, only 33% of all lending is productive finance for business purposes. Household and consumer debt continues to rise strongly. Household debt is at a record. This is one good reason (or should that be 1.42 trillion reasons?) why the RBA should not be cutting the cash rate.

Overall, only 33% of all lending is productive finance for business purposes. Household and consumer debt continues to rise strongly. Household debt is at a record. This is one good reason (or should that be 1.42 trillion reasons?) why the RBA should not be cutting the cash rate.

The difference between the RBA numbers, which covers all lending for property, and the APRA data, which covers banks only, is explained by the non-bank sector. There has been little growth here in recent times.

The difference between the RBA numbers, which covers all lending for property, and the APRA data, which covers banks only, is explained by the non-bank sector. There has been little growth here in recent times.

Another Bumper Month For Home Loans

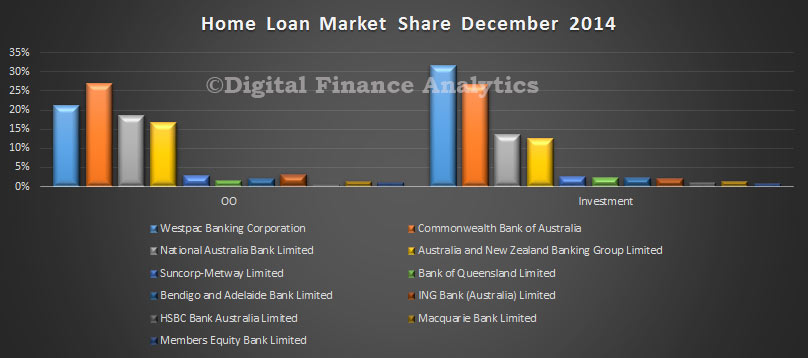

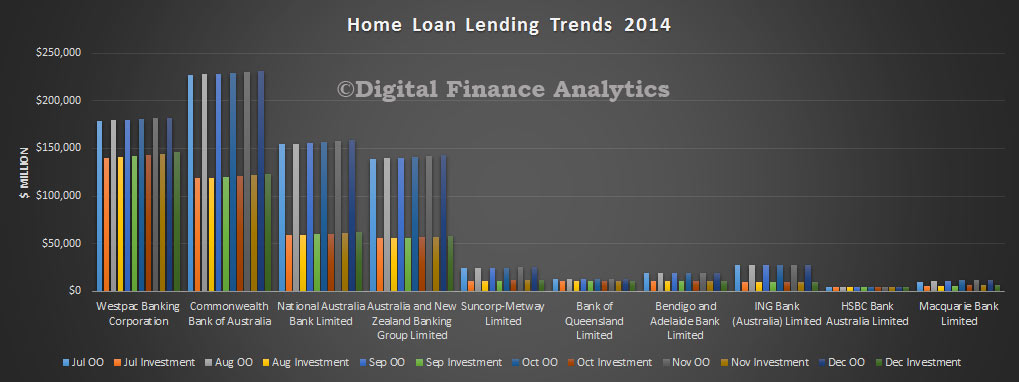

APRA just released their monthly banking statistics, which provides a view of lending and deposit portfolios from the banks (ADI’s). Overall home lending by the banks rose $9.12 billion to $1.315 trillion. Owner Occupied loans grew by 0.59% and Investment Loans by 0.9%, with Owner Occupied Lending now accounting for 65.1% of the loan book (down from 65.2% last month). Looking in more detail at the individual bank data, we see that CBA maintains its leading position in the Owner Occupied sector, whilst WBC leads the Investment Property Lending.

Looking at the trend data, we see stronger investment lending growth at WBC, and to a lesser extent at the other majors.

Looking at the trend data, we see stronger investment lending growth at WBC, and to a lesser extent at the other majors.

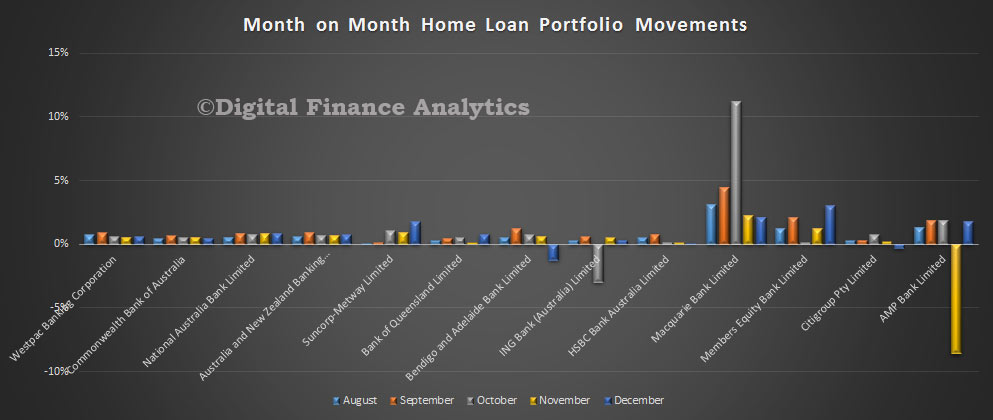

In portfolio percentage terms, Members Equity registered 3% growth, with Macquarrie at 2% and Suncorp and AMP at 1.8%, all above system growth.

In portfolio percentage terms, Members Equity registered 3% growth, with Macquarrie at 2% and Suncorp and AMP at 1.8%, all above system growth.

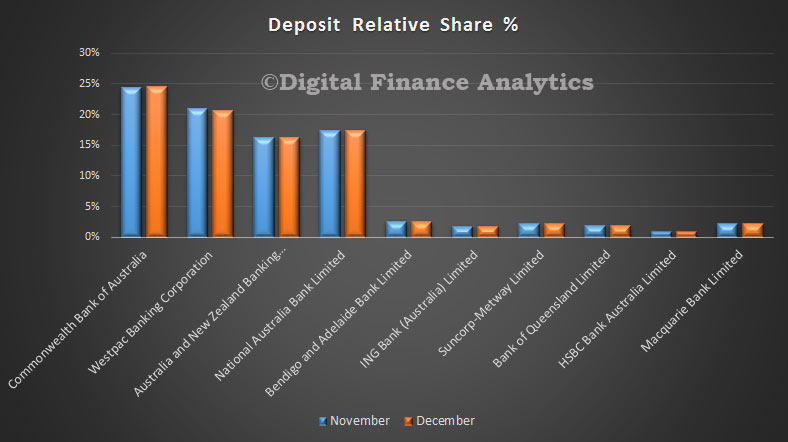

Turning to deposits, we saw growth of 1.37% in the month, to $1.8 trillion. CBA holds the largest share of deposits, with WBC and NAB following.

Turning to deposits, we saw growth of 1.37% in the month, to $1.8 trillion. CBA holds the largest share of deposits, with WBC and NAB following.

Looking at the monthly portfolio movements, we see CBA recorded portfolio growth of 1.6%, whilst WBC was 0.29%. Rabbobank grew their portfolio by 1.69%, whilst Macquarie and ING both grew their portfolios by 1.55%. We suspect some players are actively managing their deposits preferring to use wholesale funding alternatives, as we have discussed before.

Looking at the monthly portfolio movements, we see CBA recorded portfolio growth of 1.6%, whilst WBC was 0.29%. Rabbobank grew their portfolio by 1.69%, whilst Macquarie and ING both grew their portfolios by 1.55%. We suspect some players are actively managing their deposits preferring to use wholesale funding alternatives, as we have discussed before.

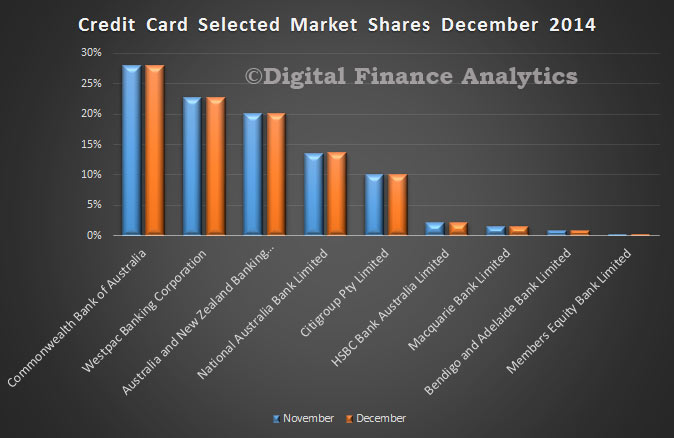

Looking at credit cards, balances rose 1.9% to $41.8 billion. There was little overall change in portfolio mix amongst the main players, and Citigroup maintained in position at number 5.

Looking at credit cards, balances rose 1.9% to $41.8 billion. There was little overall change in portfolio mix amongst the main players, and Citigroup maintained in position at number 5.

Wholesale Financial Market Reform

In a speech in London entitled “Realigning private and public interests in wholesale financial markets: the Fair and Effective Markets Review” given by Andrew Hauser, Director of Markets Strategy, Bank of England, and head of the Fair and Effective Markets Review secretariat; there is an interesting description of why Wholesale Financial Markets became relatively under-regulated, and the dimensions of reform now being considered to address this under-regulation. This is important, not just in the UK. The issues raised are universally relevant.

I’m here primarily to talk about the Fair and Effective Markets Review, a joint initiative by the Bank of England, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and HM Treasury, launched by the Governor of the Bank of England and the Chancellor last June. The aim of the Review is to reinforce confidence in wholesale fixed income, currency and commodity markets – or ‘FICC’ for short – in the wake of LIBOR, FX and other appalling cases of misconduct that have come to light since the height of the financial crisis. The Review is interested in three key questions. First, what were the root causes of this behaviour? Second, how far have the steps taken by firms and regulators since the crisis gone to put things right? And, third, what remains to be done?

Before describing the work of the Review in more detail, I want to take a bit of a step back and ask why it is that we are here at all. And that’s not as strange a question as it might first seem, because for a long period the phrase ‘wholesale banking conduct’ was thought to be something of an oxymoron. Wholesale markets were seen as being (for the most part) deep and liquid – and therefore hard to manipulate – and involving professional, well-informed, forward-looking counterparties, who could both look after their own interests, and sustain overall market integrity, through the operation of robust market discipline. To put it bluntly, firms knew that an attempt by them to abuse the interests of others in the market today could be punished by the removal of large quantities of lucrative business tomorrow. And that knowledge was thought to be the most powerful way of sustaining broadly well-functioning and sound markets. ‘Caveat emptor’ never meant ‘anything goes’ – wholesale markets have always been subject to the law on competition, fraud and misrepresentation; and the regulatory perimeter has been progressively extended across many wholesale businesses in recent years. But the size of the regulatory rulebook, and the degree of supervisory intensity, has tended to be much more modest than in markets and activities involving less well-informed retail customers.

The potential power of market discipline in maintaining market integrity has a strong intellectual appeal. If it works in the way described, it allows wholesale markets – crucial to a well-functioning global economy – to operate without the cost of too many regulatory rules. And, crucially, it delivers strong alignment between what matters for the private business success of financial market firms, and what matters for good conduct. Even where market discipline is strong, regulators still play an important role – but more as referees, with yellow or red cards to use in extremis. In such a world, the strongest constraint on the conduct of wholesale market participants comes from the knowledge that if they act inappropriately they lose the business. If they lose the business, they lose their bonuses. And, if misconduct goes too deep, firms go bust. So the incentives to make money and to ensure good conduct are aligned, and operate primarily through the business line.

Those responsible for ensuring good conduct – probably the business heads – don’t have to struggle to make themselves heard in annual pay rounds or beg traders to read manuals or attend courses. We could debate for some time whether there was a historic ‘golden age’ when the real world actually worked like this. But it clearly has not done so in recent years, which have seen a sequence of appalling market abuses involving collusion, manipulation of benchmarks and other financial market prices, structuring assets in ways designed deliberately to undermine the interests of end-investors, deliberate mis-valuation of large scale positions, and the abuse of private information for personal or corporate gain. No amount of counterparty sophistication – that key plank of the ideal model I discussed earlier – can protect you against collusion. Measured in terms of regulatory fines and damaged reputations, the cost has been large enough. But more profound still has been the damage to public trust in FICC markets, which in turn has impaired their effective operation, created uncertainty among intermediaries, investors and other end-users, diverted huge amounts of management and financial resources, and materially increased the compensation required for taking risk. Everyone recognises that these markets matter too much to the global financial system to leave these problems untouched. And that is why we are all here today.

The behaviours that have come to light strike many as being deeply immoral, and have triggered an extensive public debate about the role of ethics in banking. But what I find even more striking is that few, if any, of those behaviours were even in the firms’ own economic interests, properly construed. Quite apart from issues of social responsibility or regulatory compliance, they were bad business, and bad for the markets in which they operated. In some cases, trading desks in one part of the firm benefited at the expense of others in the same firm; in others, practices that were profitable on one day likely led to losses on others; and, more generally, persistent market misconduct risked giving firms, or entire markets, the reputation of being akin to the ‘wild west’. How did this happen? Part of the answer is that firms lost control of their trading teams, or mis-incentivised them. Conflicts of interest were allowed to range unchecked. And traders were put in positions where they could cause mortal damage to their firms’ franchises for, at best, modest profit opportunities. Now, as a direct result, firms’ senior management are being assailed with advice, demands, and ‘shoulds and shouldn’ts’ from every direction. But, for those who still believe in the basic market discipline story, the real question is: how did firms so fundamentally misunderstand their own long-term interests – and those of the markets in which they operated and on which the global economy relies? And how can those interests be re-established? In one sense, the supervisory and regulatory interventions seen since the crisis, together with the huge enforcement fines, may be seen as substitutes for the incentives to good conduct that the market failed to deliver. But if those interventions are not to have to become ever more draconian over time, we must also find ways to re-energise the discipline of the market – to return to what Governor Mark Carney has termed ‘true’ markets – free from collusion, manipulation, abuse of private information, transparent, open and competitive.

Now all of this may seem a bit high-falutin’ compared to some of the more practical questions on the agenda of this conference. Shouldn’t we just get on with finding practical steps to ensure that bad guys don’t again imperil firms’ livelihoods and reputations? Certainly that is a crucial part of it. But a repeated theme stressed to us throughout the Fair and Effective Markets Review consultation, and heard again at this conference, has been the importance of ensuring that the new structures being put in place to manage conduct are aligned with the business, and not in some sense parallel to, or outside of, it. Structures that fail to meet this test may be considered crucial today, when memories of the crisis and the enormous fines that followed are still fresh. But the risk is they get progressively de-emphasised as memories fade, budget rounds come and go, and new priorities emerge. There is currently an enormous focus on conduct in most firms, as there was after previous historical bouts of market abuse. But all of you know the challenges that can arise in trying to drive through lasting change: getting particular business lines to think outside their silos; securing adequate Board time for conduct discussions; ensuring conduct gets an appropriate weight in annual bonus round discussions – even where it conflicts with revenue considerations; or getting trading staff to attend training courses. There is at least a risk that the current focus on conduct risk may turn out to be like that annual New Year’s Resolution to visit the gym every day, refreshed no doubt sincerely every January, but looking a little threadbare by mid-year… The only way to ensure that This Time Is Different is to ensure that (a) effective market disciplines are re-established, and (b) that conduct risk management is intimately aligned with (indeed, arguably identical to) the successful running of the business, rather than something (to overstate for effect) that is done primarily to look good to the world, the regulator, or others. In that regard I found Chris Severson’s discussion of the parallel between naval aviation and banking conduct on the first day of this conference very revealing. Navy pilots don’t obsess over safety for appearance’s sake, or out of fear of a fine or court-martial from the authorities. They do it because if you’re not safe, you (or others) die. We need to ensure that incentives are similarly aligned in banking. Traders will never face the same threat to life and limb as fighter pilots. But nothing focuses the mind as effectively as the knowledge that professional demise for themselves and their teams is a real possibility if they don’t conduct themselves properly. As a recent report by Oliver Wyman put it, to get proper engagement from the frontline, conduct risk management needs to be described as good business practice rather than compliance with rules. Achieving that will require a joint effort by market participants and the public authorities – and that is a key guiding principle of our Review.

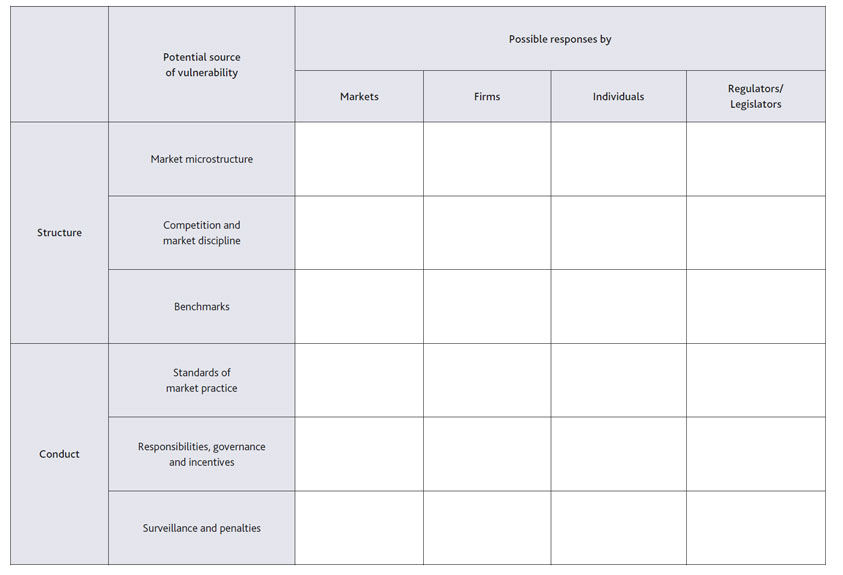

To understand why public and private incentives seem to have diverged in recent years, it is helpful to start from the ideal model I described earlier and ask where it might have broken down. When we began our Review last summer, I – perhaps naively – thought it might prove difficult to identify potential root causes. In fact, the challenge has been to limit the possible explanations to a manageable number. To help structure our analysis, therefore, the Review’s consultation document is based around the framework shown in the table below.

The vertical axis on the Table lists six key potential sources of abuse or vulnerability. Three relate to the structure of markets, and three to the conduct within them. The horizontal axis of the Table is important too. Market participants have sometimes argued to us that the main failing in recent years was by regulators, who should have been more vigilant for the abuse perpetrated by a handful of ‘bad apples’, and tougher in prosecuting it. In fact, as Minouche Shafik, the Chair of the Review, has argued, the scale of the problem clearly extends beyond a few bad apples4. But even if that were not the case, I am not sure how often those making these points have thought through the consequences of espousing this view. Market participants are far closer to the day-to-day operation of markets than regulators can ever hope to be; market discipline, as I have argued, is a potent force if properly engaged; and, to put it politely, we do not tend to be overwhelmed with requests from the industry for tougher, more intrusive (and inevitably more expensive) regulation. Recommendations for further, targeted, regulatory interventions must remain part of the Review’s toolkit. But a key message we want to get across is that many of the solutions could more plausibly lie in the hands of the market, guided or catalysed by the authorities where required. In that regard we are fortunate to have the services of a dedicated Market Practitioners Panel, chaired by Elizabeth Corley of Allianz Global Investors, and consisting of senior business heads from the buy-side, sell-side and end user communities, together with infrastructure providers and independent experts. Let me briefly highlight a few of the areas in which the ideal model might have broken down, using Table A as a guide.

The first row, grandly titled ‘market microstructure’, posits that some wholesale markets may not be as deep, liquid or transparent as the ideal suggests. A key issue in the LIBOR abuses, for example, was that the benchmark was based on an exceedingly thin underlying market for unsecured interbank borrowing. Markets for some other FICC products, such as some types of corporate bonds for example, can also be highly illiquid – and, partly as a result, transparency levels can also be relatively low. Thin or ‘dark’ markets can be easier to manipulate.

The second row of the Table asks whether a lack of effective competition or market discipline may have played a role in recent abuses. Both the LIBOR and the FX misconduct cases involved striking examples of collusion between traders – indeed in the case of FX in particular, it is hard to see how any market manipulation would have been possible in such deep and liquid markets without it. Increased concentration and horizontal integration in wholesale markets in recent years may also have increased the scope of potential conflicts of interest and reduced the ability of market users to shop around – which as I mentioned earlier is such a crucial part of the historical market discipline paradigm. Many, if not most, of the recent major cases of misconduct in FICC markets, highlighted weaknesses in the design of benchmarks – which is the third and final structural category in the Table. The flaws were remarkably varied, and depended significantly on the design of individual benchmarks – LIBOR for example was insufficiently grounded in actual transactions, the WMR FX benchmark had too narrow a window, and precious metals benchmarks were insufficiently transparent. A common feature however was that the design, technology and governance arrangements around measures that had once probably been adequate for small-scale usage had failed to keep pace with the massive increase in scale and diversification of their usage, creating opportunities for abuse or misconduct that were unlikely to have been as evident when the measures were first created. There has been rapid evolution in FICC market structures under all three categories in recent years, driven by both regulatory and technological change. Under market microstructure, the G20 commitments on OTC derivatives, MiFID2 in Europe and Dodd-Frank in the US, the new post-crisis Basel capital and leverage requirements, and intense pressure on revenues and costs are all driving FICC markets towards a more transparent, standardised, agency-based trading model. Under competition, the highly integrated investment bank business model has become less economic than it once was, and multiple electronic platforms are competing for new business. And under benchmarks, there has been a massive push from regulators and administrators to strengthen the design and oversight of key measures – including the Wheatley reforms to LIBOR, the IOSCO standards for benchmarks, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) reviews of interest rate and FX benchmarks, and the Fair and Effective Markets Review’s own recommendations to bring a further seven major benchmarks into UK legislation, which have been accepted by Government. The challenge for and effective market conditions over time. Or whether further steps are needed to ensure that market discipline can again play a full role in maintaining good standards of market conduct.

The lower half of the Table covers conduct issues in FICC markets, and therefore has a more direct bearing on the issues being discussed at this conference. The fourth row asks whether the standards that market practices should adhere to have been sufficiently clear, or well understood, in FICC markets. As you will all be aware, any effective conduct programme has to start with a clear description of the behaviours that you as a firm expect to see from your staff. Enforcement cases – of which there have regrettably been many in recent years – provide one clear set of anchors for this work. But how clear are you about the appropriate standards in less egregious cases? How do you identify or promulgate appropriate ‘case law’ in FICC markets? Are the various market codes currently in existence helpful, or do they need strengthening? And is the regulatory perimeter in the right place, whether in spot FX markets or elsewhere? Once appropriate standards have been established, the fifth row of the Table asks how you establish clear accountabilities within your organisation, how you monitor and control those accountabilities, and how you ensure that incentives are appropriately aligned with good behaviour. Much of our discussion yesterday fell under this heading – and no surprise because it was arguably failings in this area more than any other that drove recent misconduct. As some of the enforcement notices vividly illustrate, either by design or by neglect, some traders were able to behave in ways that directly harmed the reputations of their own firms. How was this allowed to happen? Had responsibility for oversight been delegated too far from the so-called First Line of Defence (or trading heads)? Were incentives appropriately aligned? Were some firms Too Big to Fail, or Too Big to Manage? And how did Boards monitor conduct across their organisations?

The final row in the Table highlights the importance of having effective tools for identifying and punishing misbehaviour. Often this is seen as being primarily the responsibility of regulators – but as I think everyone now recognises that is far too much of a ‘hands off’ attitude for something that can threaten a firm’s very survival. Regulation provides a crucial backstop. But regulators have neither the data nor the resources to spot every misdemeanour – and supervisory and enforcement actions cannot substitute for developing an appropriate culture within individual firms. What surveillance tools can firms themselves install and operate? How do you develop a culture in which whistleblowing is encouraged, and decisive action is taken against breaches of standards? Is it still too easy for misbehaving traders to avoid censure by changing employers? And how and when should firms consider making disciplinary cases public as a means of sending a clear signal? As with market structure, a great deal of change is underway in an attempt to strengthen conduct. We have heard about all the supervisory work underway by the FCA. The United Kingdom has introduced, or is in the process of introducing, major new rules on remuneration, on the responsibilities of Senior Managers, and on criminal sanctions for benchmark manipulation. The FSB and the major central banks have promulgated new standards for behaviour in FX markets. We heard from Sir Richard Lambert about the important work of the Banking Standards Review Council. And, as we have been discussing over the past two days, firms have themselves invested substantial sums in new conduct risk processes. Much has been achieved since the peak of the financial crisis, on both the regulatory and private side. A key role of the Fair and Effective Markets Review is to take stock of that progress, and celebrate it where it is appropriate to do so. At the same time however some of the behaviours highlighted in the recent enforcement cases occurred worryingly recently – and in areas which seem surprisingly close, both physically and functionally, to very similar abuses in LIBOR and elsewhere that had occurred, in some cases in the same companies, only shortly before. At the very least that raises questions about the ability of firms to learn from past mistakes and think laterally about the lessons for other parts of their business. It has been encouraging to hear over the past two days about some of the ways that firms are now seeking to tackle those challenges. A question for the Review is whether these changes have gone far enough, or whether we need to provide further support to those efforts, working collaboratively with market participants wherever possible, when we produce our final recommendations in June.

To return to where I came in, we need markets to work well, in the interests of everyone. The purpose of the Fair and Effective Markets Review is not to hinder the operation of wholesale markets unnecessarily, but to return them to fairer and more effective operation. To be crystal clear, markets characterised by collusion, manipulation or abuse of private information are not working effectively. The potential power of market discipline means that, where we can work with the grain of markets, we will. Reform to internal control processes is essential, and the discussions at this conference are encouraging in that regard. But as conference participants have repeatedly emphasised, processes that operate in parallel to, or isolated from, the business, focusing on regulatory compliance, or simply preventing the re-emergence of old vulnerabilities, will not survive over the cycle – they will die out as memories fade, budget rounds come and go, and those who never believed in them spot their moment and strike. The tests are – do they work with the grain of the business and markets in which their firms operate? Do they have the engagement of senior management, because they matter to the business – not only when the supervisory lights are on, but also when they are off? Do trading staff understand they have to be involved – not because they are expected to, but because it is essential to being successful? Achieving that alignment is essential to us all – and I hope that the Fair and Effective Markets Review can play its part in that process.

The Debt Trap

In a speech given by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England in Dublin, entitled “Fortune favours the bold” there is a good summary of the debt trap which is underlying the current economic environment. The speech describes how the debt trap was set, and how it is wagging the market dog.

Setting the debt trap

Building the debt that now weighs on our economies was the work of a generation. In the decade before the crisis, private financial balances became unsustainable. UK households borrowed 4% of GDP year after year; Irish households at more than twice that rate. Household debt peaked close to 100% of GDP in the UK, and 120% in Ireland. This borrowing was largely for consumption and real estate investment rather than businesses and projects that would generate the earnings necessary to service those obligations. Property prices soared as a result. Such excesses were possible because a decade of non-inflationary, consistent expansion turned initially well-founded confidence into dangerous complacency. Beliefs grew that globalisation and technology would drive perpetual growth, and that the omniscience of central banks would deliver enduring stability.

With a growing conviction that financial innovation had transformed risk into certainty, underwriting standards slipped from responsible to reckless and bank funding strategies from conservative to cavalier. Financial innovation made it easier to borrow. Bonus schemes valued the present and discounted the future. Banks operated in a heads-I-win-tails-you-lose bubble and were capitalised for perfection. And a steady supply of foreign capital from the global savings glut – and in Ireland’s case, the initial euphoria of European Monetary Union – made it all cheaper. When the Minsky moment finally struck, debt tolerance decisively turned and the kindness of strangers evaporated. UK households swung from borrowing 4% of GDP annually to saving 2% of GDP. The comparable swing in Ireland was more than twice as large.

In the wake of the crisis, three truths came back to the fore.

- First, while asset prices rise and fall, debt endures.

- Second, the distribution of debt and assets matters.

- And third, it is very hard to reduce high debt in one sector or region without at least temporarily increasing it in another.

The debt tail is wagging the market dog.

These realities continue to weigh on the European financial system. It is often argued that the world is awash with liquidity and excessive risk taking. And yet the rain is falling unevenly on the plain leaving some regions parched and others sodden. Savings aren’t flowing freely to the areas that need them the most. This is certainly true in the euro area, where many savings are trapped and much of finance remains fragmented. The result is demand compression, weighing on the outlook for growth and sustaining fears that another major adverse shock is possible. Risk appetite is more fleeting than median growth forecasts suggest. The constellation of asset price moves since last summer bears this sober assessment out. Yields on sovereign bonds have fallen across all maturities. France hasn’t borrowed this cheaply since the ‘50s – the 1750s. Real rates are negative as far as the eye can see, suggesting perpetually anaemic growth.

In the past six months, estimates of the equity risk premium have risen by over 100bps in the UK and the euro area back to levels last seen in the heart of the crisis. In addition, the probability of large declines in equity prices implied by options prices rebounded during 2014. This all suggests that investors may be attaching some probability to very bad outcomes, possibly the tail risk of economies becoming stranded in a debt trap. This market view is mirrored in elevated corporate caution. Investment remains subdued and businesses continue to build cash in many advanced economies. This is one reason why the so-called ‘equilibrium’ real interest rate is negative in many advanced economies, though it has risen and is possibly now positive in others like the UK. Reflecting these real dynamics, central bank interest rates have had to be set at extraordinarily low levels and supplemented by large scale asset purchases simply for monetary policy to

remain neutral.

Escaping a debt trap requires a suite of measures including structural reforms to boost productivity. But above all an economy needs to be able to channel all available savings – household, corporate and foreign – to those sectors willing and able to spend.

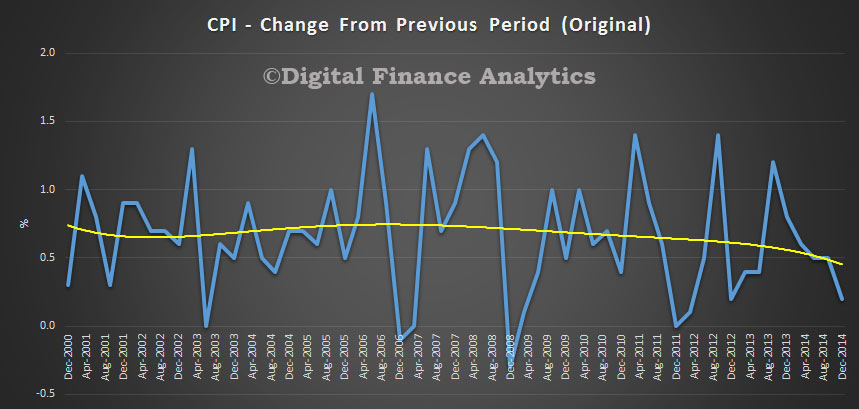

CPI Down To 1.7%

According to the ABS, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 0.2% in the December quarter 2014, following a rise of 0.5% in the September quarter 2014. The CPI is trending down at the moment.

The most significant price rises this quarter were for domestic holiday travel and accommodation (+5.8%), tobacco (+4.8%) and new dwelling purchase by owner-occupiers (+1.1%), These rises were partially offset by a fall in automotive fuel (–6.8%). Global oil markets continue to experience oversupply, which resulted in continued falls in oil prices. In Australia, average unleaded petrol prices reached a low of $1.17 per litre in December 2014, the lowest recorded average daily price since February 2009.

The CPI rose 1.7% through the year to the December quarter 2014, following a rise of 2.3% through the year to the September quarter 2014.

The fall in CPI may stimulate calls for the RBA to cut rates, but given that oil price falls already acts as a quasi rate cut, DFA believes a further cut in official rates is not required. The lower dollar and stable unemployment data also suggests there is no need for cuts, indeed, the next movement should be upwards.

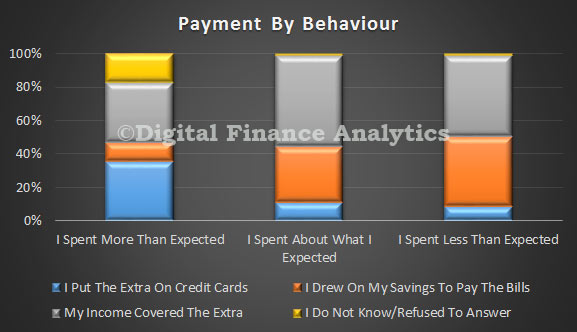

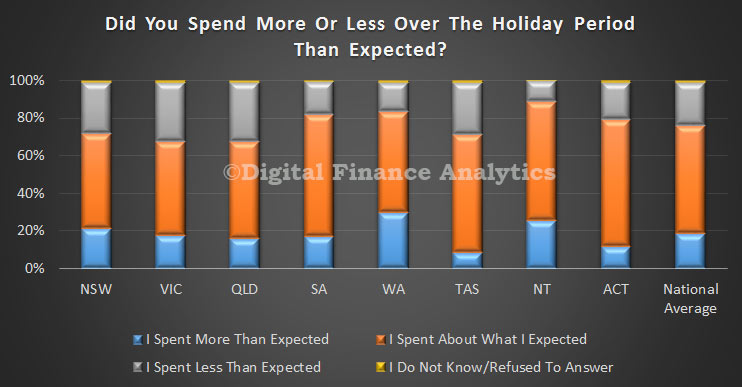

One In Five Households Spent More Than Planned Over The Summer

Using results from the DFA Household Surveys, we have been looking at household spending over the holiday period. We found that nearly 20% of households spent more than they were planning to over the break. Household behaviour varied by state. In WA more than 29% of households overspent, compared with 21% in NSW, and 8% in TAS. On the other hand, 31% of households in QLD and VIC spent less than anticipated, whilst only 11% from NT were below plan.

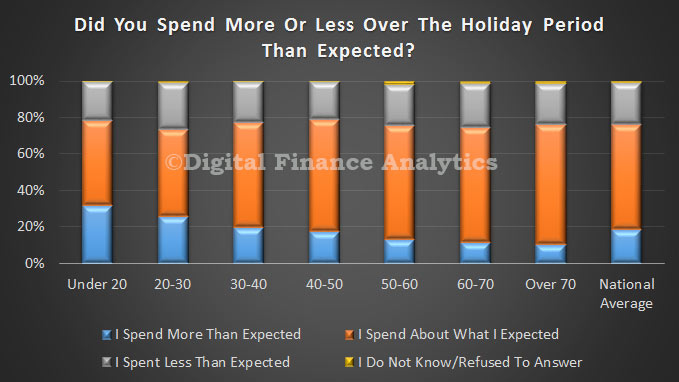

Looking at the data by age, we see that those households under 20 were most likely to spend more than planned (31.5%) whereas amongst households over 60, only 11% overspent.

Looking at the data by age, we see that those households under 20 were most likely to spend more than planned (31.5%) whereas amongst households over 60, only 11% overspent.

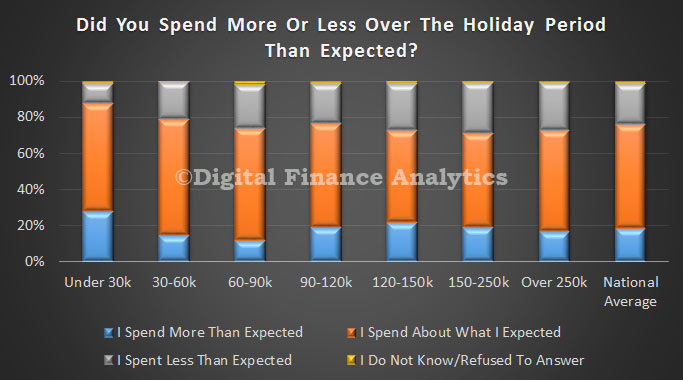

Finally, looking at income ranges, we see that those on the lowest incomes were most likely to spend more than they planned to, whilst those in the middle income ranges were more likely to spend less than expected.

Finally, looking at income ranges, we see that those on the lowest incomes were most likely to spend more than they planned to, whilst those in the middle income ranges were more likely to spend less than expected.

The survey also showed that those who overspent were most likely to use credit cards to cover the extra payments, and 17% of these did not know how they would cover the additional costs. On the other hand, those who spent as planned, or spent less than expected, were significantly less likely to use credit cards.

The survey also showed that those who overspent were most likely to use credit cards to cover the extra payments, and 17% of these did not know how they would cover the additional costs. On the other hand, those who spent as planned, or spent less than expected, were significantly less likely to use credit cards.

Global Liquidity, House Prices and the Macroeconomy

The Bank of England just published a research paper on “Global liquidity, house prices and the macroeconomy: evidence from advanced and emerging economies“. This paper compares house price cycles in advanced and emerging economies using a new quarterly house price data set covering the period 1990-2012 and models the impact of changing global liquidity, broadly understood as a proxy for the international supply of credit by aggregating bank-to-bank cross-border credit flows. They find that house prices in emerging economies grow faster, are more volatile, less persistent and less synchronised across countries than in advanced economies. They suggest that house prices amplify the response to global liquidity shocks in both advanced and emerging economies, but through different mechanisms. In advanced economies, arguably by boosting the value of housing collateral and hence supporting more household borrowing; whereas in emerging markets, by generating a lower default risk and a more appreciated exchange rate that support the international borrowing capacity of the economy.

They observe that the exchange rate seems to have a traditional shock absorbing role in advanced economies and collateral valuation effect in emerging economies. Indeed, studying the interaction between house prices and the exchange rate in models with both domestic and international financial friction may be an interesting area of future research.